New radiocarbon analysis of five dugout canoes found on the bed of Lake Bracciano 20 miles northwest of Rome have revealed the vessels are between 7,500 and 7,000 years old, the period when the first farmers migrated from the Near East throughout the Mediterranean, establishing communities in central Italy. The results, published in the journal PLOS ONE, identify the vessels as the oldest Neolithic canoes in Europe.

New radiocarbon analysis of five dugout canoes found on the bed of Lake Bracciano 20 miles northwest of Rome have revealed the vessels are between 7,500 and 7,000 years old, the period when the first farmers migrated from the Near East throughout the Mediterranean, establishing communities in central Italy. The results, published in the journal PLOS ONE, identify the vessels as the oldest Neolithic canoes in Europe.

They were discovered at the submerged site of La Marmotta, a Neolithic lakeshore village rich in archaeological remains including 3,400 piles supporting the dwellings, walls, roofs, floors and hearths. Found at a depth of about 26 feet under 10 feet of sediment, the anaerobic conditions protected the copious organic remains from decay and boring critters. The remains of domestic livestock (mostly sheep and goats, a few cattle and pigs), two canine species and a large number of wild animals attest to the community’s herding, hunting and fishing practices. Botanical remains were plentiful too, a variety of cereals, legumes and fruits, both cultivated and foraged. A wide variety of wood, basketry and textile utensils were unearthed, including spindles, bows, sickles and adzes.

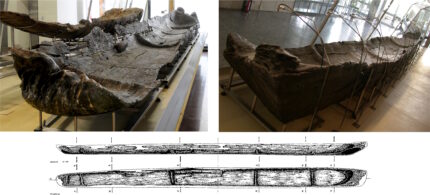

The five canoes were unearthed in a series of excavations between 1992 and 2006. Each canoe was associated with one of the dwellings. The boats are exceptional for their large size — the largest is 36 feet long — and for the advanced techniques used in their construction. Canoe 1, for example, has four transversal reinforcements carved in a trapezoidal shape that would have strengthened the hull and improved the handling of the boat. It also has three T-shaped mounts on its starboard side pierced with 2, 3 and 4 holes. They were placed at regular distances and were likely used to fasten ropes, perhaps to a sail or a stabilizer or maybe even a second boat to create a catamaran.

The five canoes were unearthed in a series of excavations between 1992 and 2006. Each canoe was associated with one of the dwellings. The boats are exceptional for their large size — the largest is 36 feet long — and for the advanced techniques used in their construction. Canoe 1, for example, has four transversal reinforcements carved in a trapezoidal shape that would have strengthened the hull and improved the handling of the boat. It also has three T-shaped mounts on its starboard side pierced with 2, 3 and 4 holes. They were placed at regular distances and were likely used to fasten ropes, perhaps to a sail or a stabilizer or maybe even a second boat to create a catamaran.

These canoes at La Marmotta, and the occupation of many islands in the eastern and central Mediterranean during the Mesolithic and particularly the early Neolithic periods, are irrefutable proof of the ability of those societies to travel across the water. This is enormously significant, because all the canoes found at European Mesolithic and Neolithic sites are associated with lakes and therefore with sailing in those waters.

In the case of La Marmotta, the size of the lake (it is now 9.3km across, but must have been smaller in the Neolithic as the shore was 300m from its current position) barely justifies the large size of a canoe nearly 11m long. It is therefore possible that they were used to cover the 38km from Lake Bracciano to the Mediterranean Sea along the River Arrone. In this way, the canoes were used both in the lake and on the sea.

The significant nautical skills needed to build and operate the boats sheds new light not just on Neolithic seafaring, but also on how these communities were structured.

The significant nautical skills needed to build and operate the boats sheds new light not just on Neolithic seafaring, but also on how these communities were structured.

There must have been people who knew how to choose the best trees, how to cut the trunk and hollow it by burning out its middle, and how to stabilise the dugout with transversal reinforcements on its base, or perhaps by the use of side poles or even parallel canoes in the form of a catamaran. To achieve this they made a series of amazingly modern artefacts, such as the T-shaped objects with two, three or four holes. These canoes and nautical technology are undoubtedly reminiscent of much more recent navigation systems. This shows that many of the major advances in sailing must have been made in the early Neolithic.

This technical complexity must be linked to social organisation in which some specialists were dedicated to particular tasks. The canoes can only be understood in a context of collective labour overseen by a craftsman who was in charge of the whole process: from cutting down the tree to launching the canoe in the lake or in the sea. These communities would therefore be well-structured in the organisation of labour, since collaboration would have been necessary to build the houses, make the canoes, procure raw materials from their sources several hundred kilometres away and put in practice certain agricultural tasks.