A 1906 verbal gypsy fortune teller machine in the gold rush ghost town of Virginia City, Montana, is being tussled over by private collectors, the state, historians and citizens. The fortune teller machine is one of no more than three remaining that used a recording to “speak” fortunes to whosoever fed it a nickel. Magician and collector of historic penny arcade games David Copperfield thinks it may be the only one of its kind remaining, and of course he wants to buy it. He’s not the only one.

A 1906 verbal gypsy fortune teller machine in the gold rush ghost town of Virginia City, Montana, is being tussled over by private collectors, the state, historians and citizens. The fortune teller machine is one of no more than three remaining that used a recording to “speak” fortunes to whosoever fed it a nickel. Magician and collector of historic penny arcade games David Copperfield thinks it may be the only one of its kind remaining, and of course he wants to buy it. He’s not the only one.

Until recently the fortune teller machine lived in relative obscurity, one dusty game artifact among the multitude collected by General Mills heir Charles Bovey. It was Bovey who began to buy up properties in Virginia City in the 1940s so they could be restored and the town kept intact as living Montana history. He did the same for neighboring gold rush ghost town Nevada City. He dedicated thirty years of his life to preserving the state’s 19th century history, and while he was it, he used the buildings to store his ever-burgeoning collection of antique games and musical machines.

Founded in 1863 as a gold rush boomtown, just two years later Virginia City had a population of 10,000 and was made capital of the newly created Montana Territory. Population followed the gold, though, and that was already moving west towards Helena. In 1875 the capital was moved to Helena where it remained when Montana joined the Union as a state in 1889. In 1942, the last mine in the area closed. Bovey jumped on the opportunity and start buying.

That boom and bust cycle not only makes Virginia City a classic example of a gold rush town, but it also ensured there was little interest in knocking down old buildings to make new ones. Bovey was able to restore a great many structures from the first decade or so of Virginia City’s life. Of almost 300 structures in town, almost half were built before 1900. The largest proportion of the 200 historic buildings in town date to the 1870s, and even the later construction is of great historical value in that it illustrates the growth and decline of frontier mining-dependent communities.

Virginia City was designated National Historic Landmark on July 4, 1961. Charles Bovey continued buying and restoring until his death in 1978. After that, his wife Sue and son Ford continued to preservation and restoration efforts until Ford sold Virginia City and Nevada City, properties, land and contents, to the State of Montana for $6.5 million in 1998. Since then, Virginia City has been under the aegis of the Montana Heritage Preservation Commission.

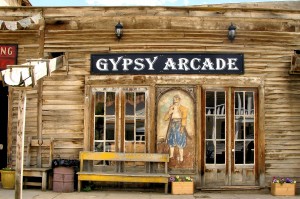

Bovey’s historical games and machines stayed in town, adding to its tourist appeal. There are hundreds of thousands of these games, most of them in curatorial storage. The fortune telling machine was used by visitors through the early 1970s when its deteriorating condition necessitated its removal to storage. It was put back on display in 1999, but it was for looking only, no touching. Conservators finally began to restore it to function in September of 2004, finishing in June, 2006. In 2008, the gypsy returned to public display (again, no touching allowed) in the Gypsy Arcade, a turn-of-the-century gadgetry museum on Virginia City’s main street.

Bovey’s historical games and machines stayed in town, adding to its tourist appeal. There are hundreds of thousands of these games, most of them in curatorial storage. The fortune telling machine was used by visitors through the early 1970s when its deteriorating condition necessitated its removal to storage. It was put back on display in 1999, but it was for looking only, no touching. Conservators finally began to restore it to function in September of 2004, finishing in June, 2006. In 2008, the gypsy returned to public display (again, no touching allowed) in the Gypsy Arcade, a turn-of-the-century gadgetry museum on Virginia City’s main street.

It was that successful restoration that brought the fortune teller to the attention of collectors. Around that time, Copperfield approached the Montana Heritage Commission offering a reported $2 million for the machine, including enough money to replace the gypsy with another non-verbal historical fortune telling machine for display purposes. They turned him down.

The pressure is back on now, though, because like most every other state-supported institution, the Heritage Commission has been kneecapped by budget cuts. You know it’s a bad sign when your curator of collections, Janna Norby, gets laid off due to budget cuts just two weeks after giving the AP a great quote for their article about the gypsy: “If we start selling our collection for money, what do we have?”

Thankfully she’s not alone in her sentiments. The current staff, skeleton though it may be, of the Heritage Commission insist that they would never sell of any of the antiques under their stewardship. This makes the private collectors grumpy because they think they can do a much better job of maintaining it and conserving it using the latest technology money can buy. Collector and restorer Theo Holstein is putting together a consortium of private collectors to bid $3 million for the gypsy. David Copperfield is revving back up to bid too, and those figures being bandied about could go even higher into the stratosphere.

Since the Montana Heritage Commission is overseen by the state Department of Commerce, which, needless to say, has slightly different priorities involving commerce rather than preservation, those millions of dollars just might be enough to pry the gypsy away from Virginia City after all. Don’t worry, though. If it disappears into a private collection never to be seen by the public again, Theo Holstein assures us that sale would be the equivalent of rescuing a precious gemstone from the dark bowels of a mine.

Since the Montana Heritage Commission is overseen by the state Department of Commerce, which, needless to say, has slightly different priorities involving commerce rather than preservation, those millions of dollars just might be enough to pry the gypsy away from Virginia City after all. Don’t worry, though. If it disappears into a private collection never to be seen by the public again, Theo Holstein assures us that sale would be the equivalent of rescuing a precious gemstone from the dark bowels of a mine.

“They don’t have any idea what they have. It’s like they have the world’s best diamond and they just pulled it out of their mineshaft. It’s good that it’s there and it survived, but now it really needs to be part of the world.”

Part of the world = hidden forever in some rich guy’s creepy basement gameland.