Gustav Klimt’s last Vienna studio, the only surviving property associated with his work, opens to the public today after almost 15 years of political struggle and an extensive renovation. The museum is not complete yet and probably won’t be for some time, but it’s close enough to welcome visitors in celebration of European Heritage Day today.

Gustav Klimt’s last Vienna studio, the only surviving property associated with his work, opens to the public today after almost 15 years of political struggle and an extensive renovation. The museum is not complete yet and probably won’t be for some time, but it’s close enough to welcome visitors in celebration of European Heritage Day today.

The villa at Feldmühlgasse 11 is very different than it was when Klimt lived and worked there from 1912 until his death in 1918. It was a modest one-story home in his day, set in a large bucolic garden that was so beautiful neighbors, visitors and later tenants raved about it for years. He rented it from furniture manufacturer Josef Hermann, whose daughter was the future wife of painter Felix Albrecht Harta. It was Harta, a friend and colleague of Klimt’s, who suggested he rent the place. Klimt made changes to the garden house, creating a large north window for his workroom and whitewashing the exterior.

The villa at Feldmühlgasse 11 is very different than it was when Klimt lived and worked there from 1912 until his death in 1918. It was a modest one-story home in his day, set in a large bucolic garden that was so beautiful neighbors, visitors and later tenants raved about it for years. He rented it from furniture manufacturer Josef Hermann, whose daughter was the future wife of painter Felix Albrecht Harta. It was Harta, a friend and colleague of Klimt’s, who suggested he rent the place. Klimt made changes to the garden house, creating a large north window for his workroom and whitewashing the exterior.

After Klimt’s death from a stroke and pneumonia in February 1918, Mrs. Helene Herrmann started making additions to the garden house, hiring an architect to plan a much larger, two-story villa over it. Construction was not complete when Josef Hermann died in 1922, but his widow, probably under some financial duress, sold the property as it was to Ernestine Werner (soon to be Mrs. Ernestine Klein) who went forward with the construction plan and had a neo-Baroque villa built on top of and around the studio, changing the house beyond recognition.

After Klimt’s death from a stroke and pneumonia in February 1918, Mrs. Helene Herrmann started making additions to the garden house, hiring an architect to plan a much larger, two-story villa over it. Construction was not complete when Josef Hermann died in 1922, but his widow, probably under some financial duress, sold the property as it was to Ernestine Werner (soon to be Mrs. Ernestine Klein) who went forward with the construction plan and had a neo-Baroque villa built on top of and around the studio, changing the house beyond recognition.

The Klein family fled to London after the Nazi takeover of Austria. The house was “Aryanized” in 1939, forcibly confiscated and sold to non-Jews. In 1948 the Austrian government returned the villa to the Klein family, but it had been sorely neglected. In 1954 the Kleins sold it back to the government for a small sum. The condition of the house was so poor that it was slated for demolition, but in 1957 the government instead turned it into a school.

At this point, Klimt had faded into obscurity. It would be another decade before shows in London and New York would bring him roaring back into the public consciousness. He was, however, still known in Austria; the property that had once housed his studio was colloquially referred to as “Klimt Villa,” but the studio was considered lost, swallowed up by all the later construction. In 1998, the villa was on its last legs. The land was scheduled to be sold to developers in lots and the villa subdivided into apartments or, what was more likely for the leaking, decrepit old structure, torn down altogether.

At this point, Klimt had faded into obscurity. It would be another decade before shows in London and New York would bring him roaring back into the public consciousness. He was, however, still known in Austria; the property that had once housed his studio was colloquially referred to as “Klimt Villa,” but the studio was considered lost, swallowed up by all the later construction. In 1998, the villa was on its last legs. The land was scheduled to be sold to developers in lots and the villa subdivided into apartments or, what was more likely for the leaking, decrepit old structure, torn down altogether.

A group of private citizens formed to fight the planned destruction of the property. They found building plans from 1922 that clearly delineated the original studio, planned new construction and showed areas slated for demolition. The plans proved that the studio was not destroyed. The garden house as it was in Klimt’s day was converted whole into the first floor of the baroque villa. Some walls were torn down, doors moved and windows changed, but the structure was intact and salvageable.

A group of private citizens formed to fight the planned destruction of the property. They found building plans from 1922 that clearly delineated the original studio, planned new construction and showed areas slated for demolition. The plans proved that the studio was not destroyed. The garden house as it was in Klimt’s day was converted whole into the first floor of the baroque villa. Some walls were torn down, doors moved and windows changed, but the structure was intact and salvageable.

The private citizens’ group formed itself into the Gustav Klimt Memorial Society in 1999. The society’s explicit aim was to rescue the Klimt Villa studio as the last property still standing that was used by the artist, and boy have they had to work for it. In 2000 they got the villa added to the list of “Historic Houses Owned by the Republic of Austria,” a designation which does not provide federal conservation protection from alteration but was at least a legal recognition of the house’s historical importance.

The political struggle to keep the house from being sold continued throughout the first decade of the millennium. Secret demolition plans kept cropping up, plans to have the house de-listed so it could be sold to Russian developers, suggestions that the villa should be stripped back to the original garden house. Finally in 2009 the villa was declared a national monument, keeping it safe from various destruction schemes. The next year a workable plan was drawn up to create a Klimt Museum in the villa, and the Austrian Ministry of Economic Affairs agreed to fund the two million euro renovation.

The political struggle to keep the house from being sold continued throughout the first decade of the millennium. Secret demolition plans kept cropping up, plans to have the house de-listed so it could be sold to Russian developers, suggestions that the villa should be stripped back to the original garden house. Finally in 2009 the villa was declared a national monument, keeping it safe from various destruction schemes. The next year a workable plan was drawn up to create a Klimt Museum in the villa, and the Austrian Ministry of Economic Affairs agreed to fund the two million euro renovation.

Construction work began in early 2011. Using written descriptions of the property from contemporaries like Egon Schiele and three photographs taken of the workroom, reception room and garden by Moritz Nähr from 1915 to right around the time of Klimt’s death, restorers were able to return the studio space to something approaching its look in Klimt’s day.

Construction work began in early 2011. Using written descriptions of the property from contemporaries like Egon Schiele and three photographs taken of the workroom, reception room and garden by Moritz Nähr from 1915 to right around the time of Klimt’s death, restorers were able to return the studio space to something approaching its look in Klimt’s day.

Here’s Schiele’s description of the Feldmühlgasse studio from just after Klimt’s death:

“Klimt decorated the garden around the house in the Feldmühlgasse with flower-beds each year- it was a delight to visit it and be in the midst of flowers and old trees. In front of the door there were two attractive heads which Klimt had sculpted. One first entered an anteroom where the door on the left led into his reception room. In the middle there was a square table; all around there were grouped displays of Japanese woodblock prints and two large Chinese pictures. On the floor there were African sculptures, and in the corner by the window there was a Japanese red-and-black suit of armour. This room led into two other rooms, where you looked out on to rose bushes.”

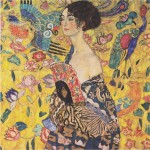

Nähr’s pictures show the reception room exactly as Schiele described it. In the workroom you can see easels with two of Klimt’s 1917 works in progress, “Lady with Fan” on the right, and “The Bride” (which he never finished) on the left. Both are now in private collections. The furniture in both rooms was designed by Josef Hoffmann, the homeowner, and most of it actually survived the war. A large wardrobe which once held Klimt’s extensive collection of Asian fabrics went to his partner Emilie Flöge after his death. It was lost along with everything he had willed her right when her apartment was destroyed just before the end of World War II.

Nähr’s pictures show the reception room exactly as Schiele described it. In the workroom you can see easels with two of Klimt’s 1917 works in progress, “Lady with Fan” on the right, and “The Bride” (which he never finished) on the left. Both are now in private collections. The furniture in both rooms was designed by Josef Hoffmann, the homeowner, and most of it actually survived the war. A large wardrobe which once held Klimt’s extensive collection of Asian fabrics went to his partner Emilie Flöge after his death. It was lost along with everything he had willed her right when her apartment was destroyed just before the end of World War II.

The rest of the furniture is in private hands today. A private collector has loaned one of the African stools from the workroom to the villa. Perhaps more will follow. Meanwhile, exact reproductions have been made to recreate the authentic look of the studio. Even the carpet in the reception room has been recreated exactly by original manufacturers Backhausen, who thankfully had a sample of the original in their archives. Visitors today will see a number of period costumes from the 1910s. There will be copies of the drawings Klimt had scattered all around the studio and two full-sized blow-ups of

The rest of the furniture is in private hands today. A private collector has loaned one of the African stools from the workroom to the villa. Perhaps more will follow. Meanwhile, exact reproductions have been made to recreate the authentic look of the studio. Even the carpet in the reception room has been recreated exactly by original manufacturers Backhausen, who thankfully had a sample of the original in their archives. Visitors today will see a number of period costumes from the 1910s. There will be copies of the drawings Klimt had scattered all around the studio and two full-sized blow-ups of the paintings in Nähr’s picture of the workroom. In a stroke of luck, Klimt’s original bathtub was found. It will be placed in one of the model waiting rooms.

the paintings in Nähr’s picture of the workroom. In a stroke of luck, Klimt’s original bathtub was found. It will be placed in one of the model waiting rooms.

Although sadly Egon Schiele’s vision of the Klimt Villa can no longer come true —

“Nothing should be removed – because everything connected with Klimt’s house is a whole and is itself a work of art which must not be destroyed. The unfinished pictures, brushes, painter’s work table and palette should not be touched and the studio should be opened as a Klimt Museum for the few who enjoy and love art.”

— at least the conclusion now has. For a somewhat terrifying look at what it took to get to this point, see this photo gallery of the restoration work from the Klimt Villa website.