The excavation of the Williams & Griffin supermarket site in Colchester has born rich fruit again. Two months ago it was historically significant bone fragments. Now, three days before the dig was scheduled to end, archaeologists have found a collection of jewelry that was hidden under the floor of a house that was destroyed when Boudicca’s forces leveled Colchester in 61 A.D.

The excavation of the Williams & Griffin supermarket site in Colchester has born rich fruit again. Two months ago it was historically significant bone fragments. Now, three days before the dig was scheduled to end, archaeologists have found a collection of jewelry that was hidden under the floor of a house that was destroyed when Boudicca’s forces leveled Colchester in 61 A.D.

The hoard was buried in a small pit dug in the initial phase of Boudicca’s revolt, when her army was marching on Colchester which, despite its population of Roman veterans, stood largely defenseless and unfortified. Archaeologists believe a wealthy Roman woman or her slave collected her valuable jewels and hid them to keep them from being pillaged and it worked, to some extent. Boudicca’s troops never did find the lady’s valuables; they just burned her house to the ground and left the treasures to be found by archaeologists 2,000 years later. The entire hoard has been removed in a solid block of soil so that it can be excavated with all due deliberation in a conservation laboratory.

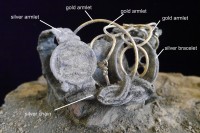

So far, archaeologists have found three gold armlets, a silver chain necklace, two silver bracelets, a silver armlet, a small bag of coins and a small jewelry box holding two pairs of gold earrings and four gold rings. When the block is fully excavated, they expect to find even more precious objects. It would be an extremely rich find no matter where it was unearthed, but it’s particularly significant given its location and the momentous events surrounding its burial. This is the first time a hoard of precious metals form the Roman era has been discovered in Colchester’s historic center.

So far, archaeologists have found three gold armlets, a silver chain necklace, two silver bracelets, a silver armlet, a small bag of coins and a small jewelry box holding two pairs of gold earrings and four gold rings. When the block is fully excavated, they expect to find even more precious objects. It would be an extremely rich find no matter where it was unearthed, but it’s particularly significant given its location and the momentous events surrounding its burial. This is the first time a hoard of precious metals form the Roman era has been discovered in Colchester’s historic center.

Its historic value is far greater than its gold and silver content. There are traces of organic remains in the hoard’s soil block, like the remains of the purse that held the coins. That’s one of the reasons archaeologists have kept it intact, so that the earth could be carefully removed without damaging even the smallest remnants of surviving textiles, leather and wood.

Its historic value is far greater than its gold and silver content. There are traces of organic remains in the hoard’s soil block, like the remains of the purse that held the coins. That’s one of the reasons archaeologists have kept it intact, so that the earth could be carefully removed without damaging even the smallest remnants of surviving textiles, leather and wood.

The lady of the house’s valuables aren’t the only remarkable survivors in the house.

Ingredients for meals that were never eaten lay burnt black on the floor of the room in which the jewellery was found. These include dates, figs, wheat, peas, and grain. (Others will almost certainly be identified when soil samples are examined by a specialist in ancient seeds and plant remains.) Foodstuffs like these would not, generally, have survived, but here they had been carbonised by the heat of the fire so that their shapes were preserved perfectly. Some of the food had been stored on a wooden shelf which collapsed during the revolt, and the remains of the carbonised remains lay on the floor. The dates appeared to have been kept on the shelf in a square wooden bowl or platter.

Under normal circumstances, a discovery of ancient precious metals would be subject to a Treasure Trove inquest. The finds would be assessed for fair market value by experts from the British Museum and the objects offered to a local museum who would then pay the finders/landowners the amount assessed. Thankfully, Fenwick Ltd, owners of the Williams & Griffin store, have decided to waive any finder’s fee they would be entitled to under the Treasure Act and donate the hoard to Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service. That means the British Museum won’t have to get involved, and the archaeologists and conservators can focus solely on the work of excavating, stabilizing and analyzing this exceptional find.