When a farmer turned up a hunk of bent bronze while ploughing a field in East Rudham, Norfolk, 12 years ago, he had no idea he’d found an archaeological treasure. He used the four-pound object as a doorstop for years and was considering throwing it out when a friend suggested he have it checked out by an archaeologist first. In 2013, the object was reviewed by Andrew Rogerson, Senior Historic Environment Officer of Norfolk’s Identification and Recording Service which is in charge of county’s Portable Antiquities Scheme. He identified it as an extremely rare and important ceremonial dirk from the Middle Bronze Age, around 1,500 B.C.

The landowner agreed to sell it to the Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery for £40,970 ($64,272). Thanks to a £38,970 grant from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and a £2,000 donation from the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society, the Norwich Castle Museum is now the proud owner of a 3,500-year-old bronze ceremonial dirk.

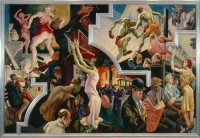

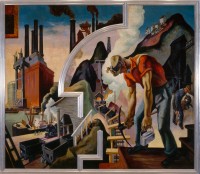

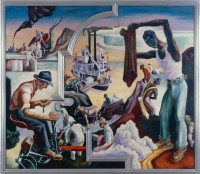

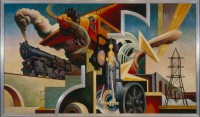

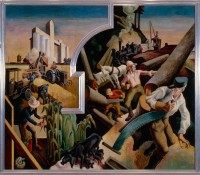

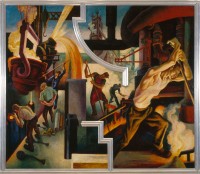

Images of Rudham Dirk courtesy of the Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

Its large size, deliberately blunt edges and the lack of rivet holes where a handle would be attached are what mark it as having no practical use. Dirks meant for actual stabbing are sharp, pointed and can be wielded easily with one hand. This piece was designed for a ritual purpose, which is why it was found folded. Bending a metal object as a symbolic act of destruction before burial was a common practice in the Bronze Age and later.

Early Bronze Age metal work was done on a small scale for local usage, much like flint knapping or the production of pottery. The Middle Bronze Age saw the development of more specialized metallurgy. Metalworking became the province of increasingly skilled artisans who would have needed workshops and apprentices and imported raw materials to create more elaborate objects. The ceremonial dirks were prestige pieces, the work of the best artisans money could buy. Owning such a heavy, large metal object intended for no practical use was a symbol of power both temporal and, given their ritual purpose, spiritual.

Bronze is composed of 90% copper and 10% tin, and it’s that 10% that was hard to come by in quantities sufficient to make a giant four-pound unusable dagger. In Bronze Age Europe, sources of tin were few and far between. There were in tin mines in the Ore Mountains on the border between Germany and the Czech Republic, on the northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Brittany in France and in Devon and Cornwall in England. The tin for the Rudham Dirk could have come from the English mines, but the artifact could have been fabricated on the continent.

Bronze is composed of 90% copper and 10% tin, and it’s that 10% that was hard to come by in quantities sufficient to make a giant four-pound unusable dagger. In Bronze Age Europe, sources of tin were few and far between. There were in tin mines in the Ore Mountains on the border between Germany and the Czech Republic, on the northwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula, in Brittany in France and in Devon and Cornwall in England. The tin for the Rudham Dirk could have come from the English mines, but the artifact could have been fabricated on the continent.

Only five other ceremonial dirks of this type have been found. Two were discovered in France — the Plougrescant Dirk (1,500–1,300 B.C.), now at the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and the Beaune Dirk (1,500–1,350 B.C.), now at the British Museum — two in the Netherlands — the co-type find the Ommerschans Dirk (1,500 – 1,100 B.C.) which at last tally was in Bavaria, still in the possession of the family who owned the estate where it was discovered, and the Jutphaas Dirk (1,800-1,500 B.C.), now in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden — and one in Oxborough, Norfolk (1,450-1,300 B.C.), which is also in the British Museum.

Only five other ceremonial dirks of this type have been found. Two were discovered in France — the Plougrescant Dirk (1,500–1,300 B.C.), now at the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and the Beaune Dirk (1,500–1,350 B.C.), now at the British Museum — two in the Netherlands — the co-type find the Ommerschans Dirk (1,500 – 1,100 B.C.) which at last tally was in Bavaria, still in the possession of the family who owned the estate where it was discovered, and the Jutphaas Dirk (1,800-1,500 B.C.), now in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden — and one in Oxborough, Norfolk (1,450-1,300 B.C.), which is also in the British Museum.

Their dimensions and details are so similar that all dirks likely came from the same workshop, perhaps even the same hand. They are virtually identical in form, decoration and cross-section. The Beaune and Ommerschans examples are the same length (68 centimeters or just short of 27 inches) as the Rudham Dirk. The Oxborough Dirk is slightly longer at 70 centimeters, while the Jutphaas Dirk is 20 centimeters shorter. If one shop is responsible for all of them, it had an impressive reach through ancient trade networks.

Their dimensions and details are so similar that all dirks likely came from the same workshop, perhaps even the same hand. They are virtually identical in form, decoration and cross-section. The Beaune and Ommerschans examples are the same length (68 centimeters or just short of 27 inches) as the Rudham Dirk. The Oxborough Dirk is slightly longer at 70 centimeters, while the Jutphaas Dirk is 20 centimeters shorter. If one shop is responsible for all of them, it had an impressive reach through ancient trade networks.

The Norwich Castle Museum’s acquisition of the Rudham Dirk is momentous not just because of the artifact’s immense rarity and archaeological significance. It’s also a homecoming that was denied them the first time a ceremonial dirk was unearthed in the county. The Oxborough Dirk was found in 1988. It was thrust into the peat vertically and erosion had exposed the hilt leaving the finder to literally stumble over it.

The artifact was exhibited at the Norwich Castle Museum in 1989 and the British Museum in 1990 before the owner decided to sell it at a Christie’s auction on July 6th, 1994. It was purchased by high society antiques dealer and notorious loot fencer Robin Symes for £51,000 ($79,076), five times the pre-sale estimate. An export block stopped it from leaving the country and gave the British Museum the time to fundraise so they could buy the dirk from Symes for the price he paid. Thanks to a £20,000 Art Fund grant, the museum was able to acquire the Oxborough Dirk later that year.

The artifact was exhibited at the Norwich Castle Museum in 1989 and the British Museum in 1990 before the owner decided to sell it at a Christie’s auction on July 6th, 1994. It was purchased by high society antiques dealer and notorious loot fencer Robin Symes for £51,000 ($79,076), five times the pre-sale estimate. An export block stopped it from leaving the country and gave the British Museum the time to fundraise so they could buy the dirk from Symes for the price he paid. Thanks to a £20,000 Art Fund grant, the museum was able to acquire the Oxborough Dirk later that year.

So it was saved for the nation, but not so much for Norfolk. The dirk visited its home county three times, twice in exhibits at the Norwich Castle Museum, last winter at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich. This time around, Norfolk’s principal museum gets to keep the rare Middle Bronze Age ceremonial dirk in the county where it was discovered, the only county in the world where two of them have been found.

Dr Tim Pestell, Senior Curator of Archaeology at Norwich Castle said: “We are delighted to have secured such an important and rare find as this, which provides us with insights into the beliefs and contacts of people at the dawn of metalworking. Through its display we hope to bring residents and visitors to Norfolk closer to the remarkable archaeology of our region and stories of our ancient past.”