In 2009, the Rijksmuseum acquired two vast collections of fashion plates: the Raymond Gaudriault Collection and the MA Ghering-van Ierlant Collection. The two collections brought more than 8,000 prints, many of the hand-colored engravings, from the year 1600 through the first half of the 20th century to the museum. It took years for curators to catalogue and document this exceptional record of historical clothing and costume. This month, more than 300 prints will go on display for the first time at the New for Now: The Origin of Fashion Magazines exhibition which runs from June 12th to September 27th, 2015.

In 2009, the Rijksmuseum acquired two vast collections of fashion plates: the Raymond Gaudriault Collection and the MA Ghering-van Ierlant Collection. The two collections brought more than 8,000 prints, many of the hand-colored engravings, from the year 1600 through the first half of the 20th century to the museum. It took years for curators to catalogue and document this exceptional record of historical clothing and costume. This month, more than 300 prints will go on display for the first time at the New for Now: The Origin of Fashion Magazines exhibition which runs from June 12th to September 27th, 2015.

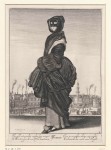

The first fashion plates — mechanically reproduced portraits depicting the contemporary clothes worn in given place and time rather than a specific individual — appeared in the 16th century. Books like Omnium fere gentium nostrae aetatis habitus (1563) by Ferdinando Bertelli and Trachtenbuch (1577) by Hans Weigel showed what people wore in different countries in significant detail. Books on what different classes wore within one country, on hairstyles and accessories followed. Bohemian printmaker Wenceslaus Hollar, a highly prolific and varied artist who made etchings of the rich and famous, landscapes, anatomical studies, maps, ruins, animals, architecture, religious subjects, heraldry and much more, published two series of costume prints of women wearing fashionable outfits, Theatrum Mulierum in 1643 and Aula Veneris in 1644.

The first fashion plates — mechanically reproduced portraits depicting the contemporary clothes worn in given place and time rather than a specific individual — appeared in the 16th century. Books like Omnium fere gentium nostrae aetatis habitus (1563) by Ferdinando Bertelli and Trachtenbuch (1577) by Hans Weigel showed what people wore in different countries in significant detail. Books on what different classes wore within one country, on hairstyles and accessories followed. Bohemian printmaker Wenceslaus Hollar, a highly prolific and varied artist who made etchings of the rich and famous, landscapes, anatomical studies, maps, ruins, animals, architecture, religious subjects, heraldry and much more, published two series of costume prints of women wearing fashionable outfits, Theatrum Mulierum in 1643 and Aula Veneris in 1644.

Thirty years later, the Mercure Galant, a periodical by Jean Donneau de Visé, published fashion plates and articles on the styles of the season in supplementary issues. France under King Louis XIV set fashion trends all over Europe. People wanted to see what courtiers were wearing and de Visé obliged. The plates were also sold separately as prints of elegantly attired men and women were increasingly popular. In the 18th century series of fashion plates were published for retail and subscription. They weren’t magazines — they were captioned but that was it as far as words were concerned — but they were periodically published glossy prints designed to make contemporary fashion look damn good.

Thirty years later, the Mercure Galant, a periodical by Jean Donneau de Visé, published fashion plates and articles on the styles of the season in supplementary issues. France under King Louis XIV set fashion trends all over Europe. People wanted to see what courtiers were wearing and de Visé obliged. The plates were also sold separately as prints of elegantly attired men and women were increasingly popular. In the 18th century series of fashion plates were published for retail and subscription. They weren’t magazines — they were captioned but that was it as far as words were concerned — but they were periodically published glossy prints designed to make contemporary fashion look damn good.

The publishers of fashion prints did everything to make their product as attractive as possible. They attracted skilled illustrators for this purpose, some of whom went on to become specialists in this area: true ‘fashion illustrators’. The trick was to portray the models on the prints as skillfully as possible and with a great sense of elegance. The printmaker was responsible for transferring the design sketches onto an engraving that could reproduce the design. A so-called ‘colourist’ subsequently added colours to each individual image by hand.

This painstaking process continued well into the age of multi-colored lithography because brilliant, varied colors and crisp details were of paramount importance in making the clothes look their best.

In the second half of the 18th century, the periodicals like the Galerie des Modes et Costumes Francais and the Collection de la Parure des Dames captured the last hurrah of Ancien Régime style. They were printed in sets called cahiers (notebooks) in the decade before the French Revolution and they celebrated the indulgence and extravagance of aristocratic fashion in clothing, hairstyles and accessories. The French fashion spigot was nearly cut off during the Revolution when anything that suggested appreciation for nobility could land a person in front of a tribunal or in the cold embrace of Madame Guillotine.

In the second half of the 18th century, the periodicals like the Galerie des Modes et Costumes Francais and the Collection de la Parure des Dames captured the last hurrah of Ancien Régime style. They were printed in sets called cahiers (notebooks) in the decade before the French Revolution and they celebrated the indulgence and extravagance of aristocratic fashion in clothing, hairstyles and accessories. The French fashion spigot was nearly cut off during the Revolution when anything that suggested appreciation for nobility could land a person in front of a tribunal or in the cold embrace of Madame Guillotine.

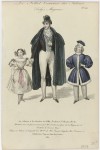

With the advent of the Directory and the revival of imperial grandeur, fashion magazines like the Journal des Dames et des Modes picked up where their predecessors had left off. The epicenter of style had shifted. No longer were the prints focused on the latest elaborate coiffure and gown worn by the First Estate at court. Muses like Josephine de Beauharnais inspired imitation, but editors like Journal des Dames et des Modes‘ Jean Baptiste Sellèque sought out the latest trends worn by fashionable people frequenting the theater, public promenades, balls the Parisian hotspots.

With the advent of the Directory and the revival of imperial grandeur, fashion magazines like the Journal des Dames et des Modes picked up where their predecessors had left off. The epicenter of style had shifted. No longer were the prints focused on the latest elaborate coiffure and gown worn by the First Estate at court. Muses like Josephine de Beauharnais inspired imitation, but editors like Journal des Dames et des Modes‘ Jean Baptiste Sellèque sought out the latest trends worn by fashionable people frequenting the theater, public promenades, balls the Parisian hotspots.

The fashion glossies spread across the continent, the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean. People wanted to see the latest in Parisian and French fashion and replicate them as closely as possible. Fashion plates were widely copied and reprinted. By the 1830s the fashion plates were accompanied by patterns giving readers a template to bring to their seamstresses or to make on their own. In the 19th century we also see the rapid development of what we now recognize as fashion magazines with more and increasingly diverse content. Issues of the Magasin des Demoiselles included editorials, plays, articles on history and nature, how-to guides, detailed explanations of the outfits in the plates and closed with a rebus.

The fashion glossies spread across the continent, the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean. People wanted to see the latest in Parisian and French fashion and replicate them as closely as possible. Fashion plates were widely copied and reprinted. By the 1830s the fashion plates were accompanied by patterns giving readers a template to bring to their seamstresses or to make on their own. In the 19th century we also see the rapid development of what we now recognize as fashion magazines with more and increasingly diverse content. Issues of the Magasin des Demoiselles included editorials, plays, articles on history and nature, how-to guides, detailed explanations of the outfits in the plates and closed with a rebus.

Even the advent of photography couldn’t stop the fashion plate. The color and detail that could be produced with illustrations remained the option of choice for fashion magazines until indoor color photography became widespread in the 1950s.

Even the advent of photography couldn’t stop the fashion plate. The color and detail that could be produced with illustrations remained the option of choice for fashion magazines until indoor color photography became widespread in the 1950s.

What makes the Rijksmuseum’s collection so signficant is that it covers almost the entire history of fashion glossies from their antecedents in the costume books well into their modern magazine setting, 400 years of what-are-they-wearing. And the best part, which I have deliberately saved for last, is that you will soon be able to browse the whole thing. The fashion plates are being digitized and integrated in the museum’s exceptional online database of high resolution photographs of the art and objects in its permanent collection. While they’re not quite done with the digitization project, there are already thousands of images you can peruse. I  count 5,915 plates uploaded as of this moment although some of them — almost all of them from the 20th century — have no photographs attached yet.

count 5,915 plates uploaded as of this moment although some of them — almost all of them from the 20th century — have no photographs attached yet.

Have I scrolled through all 5,915 search results, you ask? Yes. Yes I have. It’s historical fashion porn of the highest quality. You can refine the search to narrow them down by date, place, maker, etc. if you’re looking for something in particular, or you can just spend the forseeable future bingeing on the whole beautiful buffet of style.