Researchers have identified the oldest known tea in Britain in the stores of the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. The small box of loose-leaf green tea is part of a collection of “Vegetables and Vegetable Substances” that was bequeathed to the nation by Hans Sloane, physician to three monarchs in a row, president of the Royal Society and avid collector of curiosities. Sloane’s natural history specimens became the nucleus of the NHM when in 1881 it became a museum in its own right instead of the neglected and abused natural history department of the British Museum, so this box of tea has been there since the very beginning.

Researchers have identified the oldest known tea in Britain in the stores of the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. The small box of loose-leaf green tea is part of a collection of “Vegetables and Vegetable Substances” that was bequeathed to the nation by Hans Sloane, physician to three monarchs in a row, president of the Royal Society and avid collector of curiosities. Sloane’s natural history specimens became the nucleus of the NHM when in 1881 it became a museum in its own right instead of the neglected and abused natural history department of the British Museum, so this box of tea has been there since the very beginning.

It wasn’t until a recent study of the Vegetable Substances collection that the specimen was properly documented and made easily accessible to scholars. PhD candidate Victoria Pickering, who is doing her doctoral studies on Sloane’s Vegetable Substances, created a searchable digital transcript of the catalogue. That’s why historians from Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) were able to find the sample while researching an upcoming book on the history of tea, and they’re the ones who pinned down its age and historical significance.

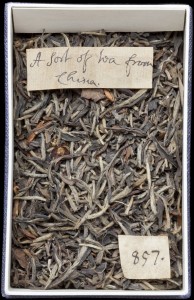

The tea is labeled “A sort of tea from China” and note marks it as a gift “from Mr Cuninghame.” That is the clue that helped establish the age of the tea. James Cuninghame was a Scottish surgeon, explorer and dedicated specimen hunter who had gotten in touch with Hans Sloane, then Secretary to the Royal Society, after returning from a voyage to the East Indies in 1696. The next year Cuninghame boarded the private trading ship Tuscan on its illicit (because it violated the East India Company and New Company’s monopoly on Asian trade) voyage to the Chinese city of Amoy, today’s Xiamen. There he collected a large number of plant and animal specimens for Sloane. Upon Cuninghame’s return in 1699, Sloane was so delighted with the haul he nominated his friend for election as a fellow of the Royal Society. Cuninghame’s Amoy specimens were the first collected by a European in China to arrive safe and intact back home.

The tea is labeled “A sort of tea from China” and note marks it as a gift “from Mr Cuninghame.” That is the clue that helped establish the age of the tea. James Cuninghame was a Scottish surgeon, explorer and dedicated specimen hunter who had gotten in touch with Hans Sloane, then Secretary to the Royal Society, after returning from a voyage to the East Indies in 1696. The next year Cuninghame boarded the private trading ship Tuscan on its illicit (because it violated the East India Company and New Company’s monopoly on Asian trade) voyage to the Chinese city of Amoy, today’s Xiamen. There he collected a large number of plant and animal specimens for Sloane. Upon Cuninghame’s return in 1699, Sloane was so delighted with the haul he nominated his friend for election as a fellow of the Royal Society. Cuninghame’s Amoy specimens were the first collected by a European in China to arrive safe and intact back home.

Cuninghame went back to China just six months later, this time on an authorized East India Company (EIC) ship the Eaton. That authorization didn’t make things easier the second time around. Cuninghame’s was ship’s surgeon so he was inextricably connected to the trade mission. The mission failed in China so in 1702 they moved on to the island of Pulo Condore in what is today Vietnam. The settlement and garrison were obliterated in 1705 when the locals massacred almost everyone for reasons that are unclear today. Cuninghame was one of few survivors. He was wounded, though, and taken prisoner for two years. After his release in 1707, Cuninghame was sent by the EIC to its trading post in Banjarmassin, southeastern Borneo. That settlement was also attacked by locals three weeks after Cuninghame’s arrival. That’s when the good doctor decided it was time to head home. He wrote to Sloane in January of 1709 telling him he was on his way back. That was the last anybody heard from him. The ship that was bringing him home, the Anna, disappeared without a trace.

Because Cuninghame regularly sent specimens to his correspondents back home while he was still abroad, the tea could have been collected when he was in Amoy (1698-99) or when he was in Chusan (present-day Zhoushan) between 1700 and 1702. The Amoy collection was larger with many dried plant specimens and Amoy was an early center for the tea trade, but tea was also grown and processed in Chusan and we know he found wild tea plants there and witnessed its manufacture.

Because Cuninghame regularly sent specimens to his correspondents back home while he was still abroad, the tea could have been collected when he was in Amoy (1698-99) or when he was in Chusan (present-day Zhoushan) between 1700 and 1702. The Amoy collection was larger with many dried plant specimens and Amoy was an early center for the tea trade, but tea was also grown and processed in Chusan and we know he found wild tea plants there and witnessed its manufacture.

Ubiquitous today, the common cup of tea was once considered an exotic and fashionable pleasure. [QMUL researcher and co-author of the book Dr. Richard] Coulton says the consumption of tea in Britain did not become widespread until decades later.

“In the seventeenth century, the simple act of blending hot water with infused leaves was considered pretty extraordinary. It was priced as a luxury item and the best tea was ten times more expensive than the best coffee. In 1663, tea was priced at up to 60 shillings per pound for the finest quality, whereas the best coffee was only six shillings per pound. What makes this discovery so fascinating is that it captures the very moment at which tea was about to lay claim to a mass market in Britain.” […]

“The tea is loose-leaf green tea, manufactured by peasant labourers on small-holdings in China. The basic process for manual tea production hasn’t really changed, so we might assume that this tea would have tasted much like an artisanal green tea today, albeit one of the rough-and-ready rather than boutique variety. The ‘green’-ness of the tea is interesting: for its first half century, so 1650-1700, Britain’s tea-habit was almost entirely green. It wasn’t until the second quarter of the eighteenth century that darker teas started to take over.”

For more about the early history of tea in England, see this excellent blog by the Queen Mary University of London research team. Their book, Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf that Conquered the World, is available for pre-order on Amazon, but can be purchased directly from the publisher now.