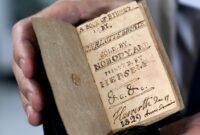

The Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, West Yorkshire, has acquired A Book of Rhymes, a newly-rediscovered miniature manuscript written and hand-bound by Charlotte Brontë in 1829. Just 3.8 x 2.5 inches, smaller than a playing card, the 15-page manuscript was the last mini-book of Charlotte Brontë’s known to be in private hands. It will now return to Charlotte’s childhood home where it was written.

The Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, West Yorkshire, has acquired A Book of Rhymes, a newly-rediscovered miniature manuscript written and hand-bound by Charlotte Brontë in 1829. Just 3.8 x 2.5 inches, smaller than a playing card, the 15-page manuscript was the last mini-book of Charlotte Brontë’s known to be in private hands. It will now return to Charlotte’s childhood home where it was written.

Between August and December of 1829, Charlotte and her brother Branwell produced six issues of a miniature magazine they named Blackwood’s Young Men’s Magazine. In 1830 they rebranded the publication as The Young Men’s Magazine and released another six issues between August and December. The manuscripts were written in tiny handwriting mimicking the regularity of print and bound with hand-sewn covers made of sugar paper.

They were inspired by the real literary periodicals like Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine that the family read avidly. Each issue contained short stories, poetry, art critiques and even advertisements, all set against the context of the city of Glasstown, capital of Angria, the imaginary world the Brontë siblings had invented as the background story for a box of 12 toy soldiers Branwell had been given for his 9th birthday.

A BOOK OF RHYMES comprises : i). The Beauty of Nature; ii). A Short Poem; iii). Meditations while Journeying in a Canadian Forest; iv). Song of an Exile; v). On Seeing the Ruins of the Tower of Babel; vi). A Thing of fourteen lines; vii). A Bit of a rhyme; viii). Lines written on the Bank of a River one fine Summer Evening; ix). Spring, a Song; x). Autumn, a Song. xi). Contents.

On the verso of her title page, Charlotte writes: “The following are attempts at rhyming of an inferior nature it must be acknowledged but they are nevertheless my best.” At the end of this Book of “Ryhmes” she refers to the secondary world created by the Brontë children amongst themselves, while asserting her authorship and creative control over that world:

“This book is written by myself but I pretend that the Marquis of Duro & Lord Charles Wellesley in the Young Men’s World have written one like it, & the Songs marked in the Index so * are written by the Marquis of Duro and those marked so † are written by Lord Charles Wellesley.” At the head of the page she also alludes to one of her best known early productions, Tales of the Islanders: “I began this book, the second volume of the Tales of the Islanders, 2 magazines for December, and the Characters of the most Celebrated Men of the Present time on the 26th of October, 1829, & finished them all by the 17 of December, 1829”.

The mini-manuscripts were kept together for decades after Charlotte’s death in 1855, first by her widower Rev. A.B. Nicholls, then by the reverend’s second wife. A Book of Rhymes was known to Brontë scholars because the 10 poems in the book were listed in the catalogue of works Charlotte compiled in her own hand and mentioned in Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1857 biography of Charlotte, but none of the poems had ever been published. After the second Mrs. Nicholls died, the manuscripts were sold off by her estate and dispersed into British and US collections.

A Book of Rhymes was last seen in November 1916 when it was sold in New York and then disappeared from public view altogether for more than a century. It emerged again four weeks ago when James Cummins Bookseller announced it had been rediscovered in a private collection and would be sold at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair on April 21st. The price tag was $1.25 million.

The seller was an anonymous private collector who thankfully prioritized the long-term preservation of the book. James Cummins Bookseller reached out to the Friends of the National Libraries in the UK and offered them first dibs if they could raise the purchase price. They only had two weeks to accomplish this daunting task. The organization reached out to multiple institutional and private donors and was able to meet the goal just under the wire. Once the sale was made, the Friends of the National Libraries donated the little book to the Haworth Parsonage Museum which is already home to nine other little books and will soon welcome another seven from the Blavatnik Honresfield Library.

The Haworth Parsonage Museum will conserve and digitize A Book of Ryhmes before putting it on display later this year.