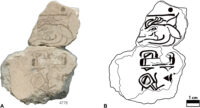

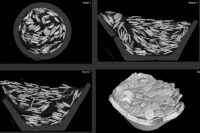

A section of mosaic flooring from the 5th century palace of Ostrogoth king Theodoric has been discovered in Verona. The mosaic was found during installation of new gas pipes in the Montorio hamlet less than four miles from Verona’s historic town center.

A section of mosaic flooring from the 5th century palace of Ostrogoth king Theodoric has been discovered in Verona. The mosaic was found during installation of new gas pipes in the Montorio hamlet less than four miles from Verona’s historic town center.

Remains of an enormous country villa more than five acres in surface area have been turning up in Montorio since the 19th century. While there is no direct evidence that it was one Theodoric’s many palaces, the sheer size and scale strongly suggests it was a royal estate. If it wasn’t Theodoric’s palace, it must have belonged to someone of enormous wealth who was very close to him.

Theodoric was not technically a Roman emperor. He was three different varieties of king, though, starting in 475 A.D. as King of the Ostrogoths, then adding King of Italy in 493 and of the Visigoths in 511. By the time of his death in 526, Theodoric reigned over most of what had been the Western Roman Empire. He spent his childhood as a noble hostage at the imperial court in Constantinople and was educated there in the Eastern Roman tradition.

As ruler of a territory stretching from the Atlantic to the Danube, Theodoric embraced the ancient imperial trappings. He donned the purple, accepted the regalia of the Western Empire from Eastern Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus and allowed all Roman citizens in the kingdom to be governed by Roman judicial law. He instituted a vast program of reconstruction of Roman cities and infrastructure, restoring ancient aqueducts, baths, churches, the Aurelian walls of Rome and the defensive walls of a myriad other cities in Italy. He threw in a few new palaces for himself while he was at it, most famously in his capital of Ravenna, but also in other northern Italian cities like Verona.

As ruler of a territory stretching from the Atlantic to the Danube, Theodoric embraced the ancient imperial trappings. He donned the purple, accepted the regalia of the Western Empire from Eastern Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus and allowed all Roman citizens in the kingdom to be governed by Roman judicial law. He instituted a vast program of reconstruction of Roman cities and infrastructure, restoring ancient aqueducts, baths, churches, the Aurelian walls of Rome and the defensive walls of a myriad other cities in Italy. He threw in a few new palaces for himself while he was at it, most famously in his capital of Ravenna, but also in other northern Italian cities like Verona.

The mosaic will remain in situ. It will be cleaned and documented in detail before being reburied. Some local residents have proposed covering it with plexiglass so the mosaic can still be seen, something that has been done already in Verona’s historic center, but this mosaic is in a terribly awkward position, trapped under networks of old pipes surrounded by homes, so it’s not a good candidate for display, unfortunately.