The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has returned an ancient Egyptian clay child sarcophagus to Uppsala University’s Museum Gustavianum more than 50 years after it was stolen under mysterious circumstances.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has returned an ancient Egyptian clay child sarcophagus to Uppsala University’s Museum Gustavianum more than 50 years after it was stolen under mysterious circumstances.

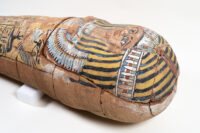

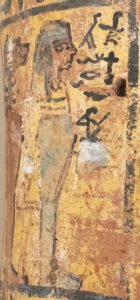

Made of alluvial clay, the sarcophagus dates to the 19th Dynasty (1295–1186 B.C.). It is 43 inches high and vividly painted. The child is depicted wearing a headdress of blue and yellow stripes tied with a headband of white, blue and red lotuses. Lotus petals cover the collar on his chest. The head and chest are on a cut-out section that can be removed to access the interior. Beneath the collar are more lotus flowers, wadjet eyes and the goddess Nut with outstretched wings flanked by Anubis seated jackals. The bottom part of the sarcophagus is covered with hieroglyphs identifying the deceased as a boy named Pa-nefer-neb.

The MFA Boston acquired it in 1985, and the ownership record seemed to be thorough and above-board, even at a time when museum’s paid zero attention to that sort of thing. It was sold by one Olaf Liden claiming to be an agent of Swedish artist Eric Ståhl (1918–1999). A letter ostensibly written by Ståhl described how he had personally discovered the sarcophagus in Amada, Egypt, in 1937, and the Egyptian government had later gifted it to him for his aid in the archaeological rescue operations before construction of the Aswan Dam. The coffin’s authenticity was attested to in writing by Swedish experts.

The MFA Boston acquired it in 1985, and the ownership record seemed to be thorough and above-board, even at a time when museum’s paid zero attention to that sort of thing. It was sold by one Olaf Liden claiming to be an agent of Swedish artist Eric Ståhl (1918–1999). A letter ostensibly written by Ståhl described how he had personally discovered the sarcophagus in Amada, Egypt, in 1937, and the Egyptian government had later gifted it to him for his aid in the archaeological rescue operations before construction of the Aswan Dam. The coffin’s authenticity was attested to in writing by Swedish experts.

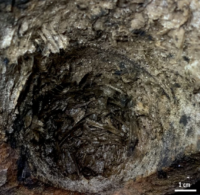

It was the MFA itself that realized this story was complete fiction, that Ståhl was never involved in any archaeological excavations in Egypt, that the letter and authentication documents were forged and the sarcophagus had been purloined from the Swedish museum, smuggled to Boston and fraudulently sold. The trigger was the 2008 publication of previously unseen photographs from the archive of the Petrie Museum. The sarcophagus was in one of the pictures: a shot of a 1920 archaeological excavation in Gurob, Egypt, by the British School of Archaeology under the direction of British archaeologist Flinders Petrie. A note with the photograph stated the coffin had been given to Uppsala University in 1922 as part of the partage system that was common at the time. All institutions involved in digs got a cut of the artifacts, basically, in exchange for their funding and fieldwork.

It was the MFA itself that realized this story was complete fiction, that Ståhl was never involved in any archaeological excavations in Egypt, that the letter and authentication documents were forged and the sarcophagus had been purloined from the Swedish museum, smuggled to Boston and fraudulently sold. The trigger was the 2008 publication of previously unseen photographs from the archive of the Petrie Museum. The sarcophagus was in one of the pictures: a shot of a 1920 archaeological excavation in Gurob, Egypt, by the British School of Archaeology under the direction of British archaeologist Flinders Petrie. A note with the photograph stated the coffin had been given to Uppsala University in 1922 as part of the partage system that was common at the time. All institutions involved in digs got a cut of the artifacts, basically, in exchange for their funding and fieldwork.

MFA curators initiated an investigation and contacted the Gustavianum to let them know about the discrepancy. Provenance researchers from both museums cooperated and shared information during the process. They found that the sarcophagus went missing from the museum’s stores in 1970 or earlier. It was not deaccessioned or traded. Both parties came to the same conclusion: the coffin had been taken from the Gustavianum illegally and should be returned.

“It is very gratifying that this return has now come to pass. The child’s sarcophagus is an important item in our collections and it means a lot to the museum and the University that it has now been returned to us. The sarcophagus is an excellent complement to our Egyptian collections and will now be available for research,” says Mikael Ahlund, Museum Director of Gustavianum, or Uppsala University Museum. “But the sarcophagus needs some work and it will be some time before it can be shown to the public in Gustavianum,” he adds.

You can see the petite coffin being unpacked upon its return to Sweden in this video.