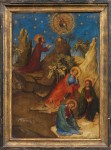

Conservators at Madrid’s Prado Museum have uncovered a rare portrait of Louis I, Duke of Orléans, son of Charles V of France and brother of Charles VI, hidden under overpaint in The Agony in the Garden, a 15th-century French painting depicting Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane while Peter, John and James slumber. The museum first encountered the work in February of 2011, when the private owner offered it to the Prado for study and potential acquisition. The lab gave it the full analytical monty: ultraviolet photography, X-rays, Infra-red reflectography, tests on the pigments and the panel.

Conservators at Madrid’s Prado Museum have uncovered a rare portrait of Louis I, Duke of Orléans, son of Charles V of France and brother of Charles VI, hidden under overpaint in The Agony in the Garden, a 15th-century French painting depicting Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane while Peter, John and James slumber. The museum first encountered the work in February of 2011, when the private owner offered it to the Prado for study and potential acquisition. The lab gave it the full analytical monty: ultraviolet photography, X-rays, Infra-red reflectography, tests on the pigments and the panel.

They found that the painting was an extremely high quality piece. The pigments contain large amounts of expensive lapis lazuli painted on a Baltic oak panel. Tree ring analysis of the oak indicated the tree was felled in 1382. The X-rays and Infra-red reflectography revealed the artist had painted two figures on the bottom left which were later painted over with a thick layer of brown. The standing figure is clearly a saint, identified by the lamb at her feet as Saint Agnes. At her feet, a male figure kneels holding a scroll and looking at the scene in the garden. The man is dressed in sumptuous clothes that were fashionable around 1400. According to painterly convention, his posture and position indicates that he was included in the painting because he or his family commissioned the work.

They found that the painting was an extremely high quality piece. The pigments contain large amounts of expensive lapis lazuli painted on a Baltic oak panel. Tree ring analysis of the oak indicated the tree was felled in 1382. The X-rays and Infra-red reflectography revealed the artist had painted two figures on the bottom left which were later painted over with a thick layer of brown. The standing figure is clearly a saint, identified by the lamb at her feet as Saint Agnes. At her feet, a male figure kneels holding a scroll and looking at the scene in the garden. The man is dressed in sumptuous clothes that were fashionable around 1400. According to painterly convention, his posture and position indicates that he was included in the painting because he or his family commissioned the work.

Conservators could not identify the kneeling figure from the X-rays. The pattern on his sleeves was a likely clue — they could be a family emblem — but it wasn’t clear what they were. Saint Agnes was another clue. She takes a protective posture in the painting so could be the patron saint of the man kneeling in front of her. Researchers looked for someone in the upper ranks of French nobility with a connection to Saint Agnes and Louis of Orléans came up. Agnes was the patron saint both of his father King Charles V, to whom he was devoted, and of his wife Valentina Visconti, daughter of the Duke of Milan.

There are only three extant portraits of Louis, all of them manuscript illuminations. If the Donor could be confirmed as Louis of Orléans, this painting would be the only one of him ever found. Restorers decided to attempt to remove the overpainting to reveal the figure if it could be accomplished without damaging the original paint. The top layer was a natural resin varnish, easily removed using a light solvent. There were two layers of overpainting, the most recent applied in the 19th century or later. The overpainting was separated from the original paint by an isolating layer of varnish, but because the original paint is a very fragile egg tempera, it was too risky to use any solvents. Instead, restorers removed the overpaint with scalpel, looking through a stereoscopic microscope at the highest magnification so they could identify non-original pigment not visible to the naked eye.

There are only three extant portraits of Louis, all of them manuscript illuminations. If the Donor could be confirmed as Louis of Orléans, this painting would be the only one of him ever found. Restorers decided to attempt to remove the overpainting to reveal the figure if it could be accomplished without damaging the original paint. The top layer was a natural resin varnish, easily removed using a light solvent. There were two layers of overpainting, the most recent applied in the 19th century or later. The overpainting was separated from the original paint by an isolating layer of varnish, but because the original paint is a very fragile egg tempera, it was too risky to use any solvents. Instead, restorers removed the overpaint with scalpel, looking through a stereoscopic microscope at the highest magnification so they could identify non-original pigment not visible to the naked eye.

Once liberated from their brown prison, the figures were revealed in all their brilliant glory. The colors were far brighter and richer than the colors on the saints and Jesus. The Donor’s scroll was found to be inscribed with the first words of the Psalm 50, aka the Miserere mei. The decorations on the sleeves turned out to be gold nettle leaves and they looked like appliqué rather than a fabric print.

The nettles were the key to the identification of Louis of Orléans. The nettle leaf was one of the duke’s emblems, one he particularly favored from 1399 until his death in 1407. Inventories of his possessions have survived and the 1403 inventory list “LXV feuilles d’or en façon d’orties,” meaning 65 gold leaves in the shape of nettles. He would have used these to decorate his clothes, like the dramatic fur-lined batwing houppelande the Donor wears in the painting.

The nettles were the key to the identification of Louis of Orléans. The nettle leaf was one of the duke’s emblems, one he particularly favored from 1399 until his death in 1407. Inventories of his possessions have survived and the 1403 inventory list “LXV feuilles d’or en façon d’orties,” meaning 65 gold leaves in the shape of nettles. He would have used these to decorate his clothes, like the dramatic fur-lined batwing houppelande the Donor wears in the painting.

Comparisons with the manuscript depictions of Louis support the identification. The distinctive nose and chin are similar in all the images, but his bald pate is only visible in the painting because Louis wears a hat in all three illuminations. He can’t wear a hat in Gethsemane, however, because he’s in the presence of God, Father and Son, no less. That makes this portrait even more remarkable.

Once Louis’ identity was pinned down, researchers were able to extrapolate from that the possible artist. There are very few surviving panel paintings from this period, and the style and quality of this one is unique so there is no means to devise attribution by comparing techniques. Louis of Orléans had painter in his household. Colart de Laon worked as a painter and as personal valet to the duke from 1391 until Louis’ death. He then did the same work for Louis’ son Charles until 1411. Contemporary sources praise him as one of the most significant artist of the day, but none of his work has been known to survive.

Once Louis’ identity was pinned down, researchers were able to extrapolate from that the possible artist. There are very few surviving panel paintings from this period, and the style and quality of this one is unique so there is no means to devise attribution by comparing techniques. Louis of Orléans had painter in his household. Colart de Laon worked as a painter and as personal valet to the duke from 1391 until Louis’ death. He then did the same work for Louis’ son Charles until 1411. Contemporary sources praise him as one of the most significant artist of the day, but none of his work has been known to survive.

This painting is a small piece, probably intended for a use in a private chapel rather than a large church. The Gethsemane theme and the Miserere mei were usually included in funerary artworks, and since Louis’ family is not included in the panel, it’s likely that it was commissioned by his wife or son after his assassination.

Louis I, Duke of Orléans, Count of Valois, Duke of Touraine, Count of Blois, Angoulême, Périgord, Dreux, and Soissons, regent of France when his older brother Charles VI, aka Charles the Mad, went insane, was assassinated by his cousin and co-regent John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. John’s courage against Ottoman forces in the Battle of Nicopolis (1396) earned him his nickname and his bullheaded vanity helped ensure his side was utterly routed. You can read all about it in one of my favorite books of all time, Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Many of these events are covered in Book IV of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, which sadly I cannot find for free online, but here’s a full version available for 90 cents.

Louis I, Duke of Orléans, Count of Valois, Duke of Touraine, Count of Blois, Angoulême, Périgord, Dreux, and Soissons, regent of France when his older brother Charles VI, aka Charles the Mad, went insane, was assassinated by his cousin and co-regent John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. John’s courage against Ottoman forces in the Battle of Nicopolis (1396) earned him his nickname and his bullheaded vanity helped ensure his side was utterly routed. You can read all about it in one of my favorite books of all time, Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Many of these events are covered in Book IV of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, which sadly I cannot find for free online, but here’s a full version available for 90 cents.

The Prado decided to purchase the painting, needless to say. They cleaned the entire thing, removing the overpaint that had darkened and dulled the rest of the figures and revealing the original brilliant color. The Agony in the Garden is now on display in Room 58A of the Villanueva Building. For more about the painting and restoration, watch these subtitled videos on the Prado’s website.

This. Is. Wonderful!

I love how (wealthy) medieval piety has given us so much info on clothing, housing & lifestyle of people that might otherwise be a mystery. Not to mention providing 3 hots & a cot for some of the best artists the world has ever known.

Liv, you’re the only other person I’ve known who claimed Tuchman’s “Mirror” as a favorite. That book weaned me off Plaidy & Co. when I was very young. It taught me that “real history” could be as fascinating as pseudo-soap operas.

She opened my door into the world & cemented my love of history. I recommend her to anyone who wants good scholarship combined with page-turning prose.

This is a particularly stellar example of medieval devotional art showcasing the lives of real people. I’m completely blown away by the gold nettle accessories being listed in the inventory and displayed in this painting. What are the odds of the primary source surviving and of this overpainted work ever giving up its secrets?

Come to my arms, fellow Tuchman fanatic! She is a role model of how to research and reveal history in the most approachable, passionate, understanding way. I love everything she’s ever written and three of her books (A Distant Mirror, The Proud Tower, The Guns of August) engendered genuine epiphanies in me and became a permanent part of my character.

What are the three parallel bars revealed in the xray? Braces to repair splits in the panel? And is there any clue to why and when Louis was painted out?

Fascinating post, as always, Mr. Drusus!

I couldn’t find out anything specific about those horizontal bars, but I suspect they are structural elements of the panel. Some sort of brackets that kept it together, perhaps? No clue as to why Louis was painted out or when the first overpaint layer was applied. The second layer could be dated because the paint type was invented in the 19th century. The one beneath it wasn’t so helpful.

Thank you! :thanks:

Liv, I read, and enjoyed, The Guns of August but my top three have to be A Distant Mirror, The Proud Tower and Bible and Sword. I also found Practicing History in a small NC library & that one put the icing on the cake.

Tuchman taught me what scholarship was FOR, not just how to do it. She breathed a soul into what I had always seen as brain exercise. Like yourself, she changed who I am. Fanatic, indeed…and proudly so.

I just ordered Practicing History from The River and I thank you for making me think about it again. I hadn’t realized it was still in print and now I can round out my collection.

In this blog, you do all the prep and cooking and I get to sit down at the feast. Doesn’t seem fair but I really do thank you.

I just wonder what Louis of Orléans did to draw Stalin’s ire?

I, too, wondered who tried to consign Louis to artistic oblivion. And why.

Maybe someone will have an idea and I thank you for asking.

Was it Stalin? I’ll have to go back & read the article again.

edahstip is referring the vanishing comissar syndrome. Not that Stalin had a hand in this particular blot out, just that it was his style to paint people out of history once they fell from his favor.

I am not an expert, but a hundred years of war with England seemingly made the French catholic. Even if, unlike Agnes, our little Agnus here comes by to sort it all out with, what ‘some’ might call almost ‘weasel-like’ features. Some other people might claim that the ‘Maître du retable de Pierre de Wissant‘ could be identified as Colart de Laon. From a hill nearby Wissant you can in fact almost see the cliffs of Dover.

Oh, Livius, thank you for brightening my day yet again! I love the sole of St. Peter’s bare foot, a couple of centuries before Caravaggio. In another life, I definitely want to be a paintings conservator.

I love all their little saintly feet. They’re so cute! They could wear Pauline Borghese’s shoes.

Me too. Canvases were costly so I can understand why artists would try and reuse old materials. But If King Charles V commissioned a painting of his son, surely the finished product would be hanging in a palace somewhere. Perhaps the royal family didn’t like the portrait and would not pay the artist.

Charles V was dead and Louis’ older brother Charles VI was on the throne by the time Louis was killed. It was his son Charles, Duke of Orléans, and his mother who would have commissioned this piece after his father’s death. Still royalty, of course, but not ruling. The painting would have been hung in a castle of theirs, perhaps the Château de Blois where Valentina lived after Louis’ death.