If you, like me, are grumpy about the complete dearth of dragons in the past two episodes of Game of Thrones, the British Library is providing a healing unguent for that burning sensation in the form of gorgeous illuminations of dragons from Medieval manuscripts. The library’s always outstanding Medieval Manuscripts blog kicked off the homage to the winged serpents of lore with a selection of diverse representations.

If you, like me, are grumpy about the complete dearth of dragons in the past two episodes of Game of Thrones, the British Library is providing a healing unguent for that burning sensation in the form of gorgeous illuminations of dragons from Medieval manuscripts. The library’s always outstanding Medieval Manuscripts blog kicked off the homage to the winged serpents of lore with a selection of diverse representations.

Dragons were popular subjects in Medieval literature, making appearances in manuscripts from Bibles to bestiaries to histories to romances to hagiographies. Although St. George may be the saint most associated with dragon-slaying today, he was far from the only holy figure to have that claim to fame. Dragons in this tradition are symbols of demonic evil and paganism, and indeed like George, many of the saints whose legends have them fighting dragons lived in the fourth century when the battle between Christianity and the traditional polytheistic religions came to a head.

The late 4th century bishop Mercurialis of Forlì, the first bishop of the city, slew a dragon and saved the Forlians from a fate worse than death (ie, their own pre-Christian beliefs). Early 4th century Saint Theodore of Amasea (aka St. Theodore of Tyro), who burned down a temple of Cybele was martyred for refusing to join in pagan sacrifice while a soldier in the Roman army, killed a dragon with a cross. Saint Margaret of Antioch (d. 304), daughter of a pagan priest who disowned her when she became a Christian and dedicated her virginity to God, slew a dragon from the inside out. Tortured by a Roman governor and would-be suitor, Margaret was swallowed by Satan in the form of the dragon only to burst out of its belly holding after making the sign of the cross. St. George himself defeated the maiden-devouring dragon after crossing himself, and the grateful population of “Silene” (it’s uncertain which city the legend refers to) convert to Christianity in response.

The late 4th century bishop Mercurialis of Forlì, the first bishop of the city, slew a dragon and saved the Forlians from a fate worse than death (ie, their own pre-Christian beliefs). Early 4th century Saint Theodore of Amasea (aka St. Theodore of Tyro), who burned down a temple of Cybele was martyred for refusing to join in pagan sacrifice while a soldier in the Roman army, killed a dragon with a cross. Saint Margaret of Antioch (d. 304), daughter of a pagan priest who disowned her when she became a Christian and dedicated her virginity to God, slew a dragon from the inside out. Tortured by a Roman governor and would-be suitor, Margaret was swallowed by Satan in the form of the dragon only to burst out of its belly holding after making the sign of the cross. St. George himself defeated the maiden-devouring dragon after crossing himself, and the grateful population of “Silene” (it’s uncertain which city the legend refers to) convert to Christianity in response.

This association of saint-slain dragons with victory of paganism is made explicit in many of the hagiographies. Here’s an instructive passage from the Life of Saint Silvester in the Golden Legend, a popular compendium of the lives of saints compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in 1275:

In this time it happed that there was at Rome a dragon in a pit, which every day slew with his breath more than three hundred men. Then came the bishops of the idols unto the emperor and said unto him: O thou most holy emperor, sith the time that thou hast received christian faith the dragon which is in yonder fosse or pit slayeth every day with his breath more than three hundred men. Then sent the emperor for S. Silvester and asked counsel of him of this matter. S. Silvester answered that by the might of God he promised to make him cease of his hurt and blessure of this people.

Then S Silvester put himself to prayer, and S. Peter appeared to him and said: Go surely to the dragon and the two priests that be with thee take in thy company, and when thou shalt come to him thou shalt say to him in this manner: Our Lord Jesu Christ which was born of the Virgin Mary, crucified, buried and arose, and now sitteth on the right side of the Father, this is he that shall come to deem and judge the living and the dead, I commend thee Sathanas that thou abide him in this place till he come. Then thou shalt bind his mouth with a thread, and seal it with thy seal, wherein is the imprint of the cross. Then thou and the two priests shall come to me whole and safe, and such bread as I shall make ready for you ye shall eat.

Thus as S. Peter had said, S. Silvester did. And when he came to the pit, he descended down one hundred and fifty steps, bearing with him two lanterns, and found the dragon, and said the words that S. Peter had said to him, and bound his mouth with the thread, and sealed it, and after returned, and as he came upward again he met with two enchanters which followed him for to see if he descended, which were almost dead of the stench of the dragon, whom he brought with him whole and sound, which anon were baptized, with a great multitude of people with them. Thus was the city of Rome delivered from double death, that was from the culture and worshipping of false idols, and from the venom of the dragon

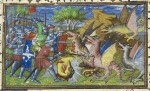

Aside from those in the lives of saints, I think my favorite dragons from the Medieval Manuscripts selection are the ones battled by Alexander the Great. Alexander became a chivalric hero in the Medieval romances and as such had several confrontations with fantastical creatures. In the French illuminated manuscript Le livre et la vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre (c. 1420 -1425), which you can browse in glorious high resolution here, he fights dragons with large emeralds embedded in their heads, dragon with ram horns and dragons with two heads, eight legs and multiple eyes on their torsos.

Aside from those in the lives of saints, I think my favorite dragons from the Medieval Manuscripts selection are the ones battled by Alexander the Great. Alexander became a chivalric hero in the Medieval romances and as such had several confrontations with fantastical creatures. In the French illuminated manuscript Le livre et la vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre (c. 1420 -1425), which you can browse in glorious high resolution here, he fights dragons with large emeralds embedded in their heads, dragon with ram horns and dragons with two heads, eight legs and multiple eyes on their torsos.

The mythologizing of Alexander the Great started in antiquity, with the source of many of these fantastical stories in the Medieval romances going back to a Greek language biography by Pseudo-Callisthenes, an unknown author from the 3rd century. Another ancient source the Medieval writers relied on heavily was the Historia Alexandri Magni by Quintus Curtius Rufus, a 1st century historian who used the character Alexander to teach lessons about proper kingship versus tyranny, a subject people who lived under Julio-Claudian rule obviously had a strong personal interest in exploring.

The Historia Alexandri Magni is incomplete, with the first two books and parts of the remaining eight lost, but that didn’t stop authors like Walter of Châtillon in the 12th century and the Archpriest Leo in the 10th century from writing epic poems and prose in Latin based on the Historia. They just filled in the blanks with bits from other sources (like the Greek version of a heavily mythological Persian history of Alexander that was translated by Simeon Seth, an 11th century Jewish doctor and chamberlain to Byzantine Emperor Michael VII Doukas) and from their own fertile imaginations. Le livre et la vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre is a French treatment of Archpriest Leo’s Historia de preliis Alexandri Magni.

The Historia Alexandri Magni is incomplete, with the first two books and parts of the remaining eight lost, but that didn’t stop authors like Walter of Châtillon in the 12th century and the Archpriest Leo in the 10th century from writing epic poems and prose in Latin based on the Historia. They just filled in the blanks with bits from other sources (like the Greek version of a heavily mythological Persian history of Alexander that was translated by Simeon Seth, an 11th century Jewish doctor and chamberlain to Byzantine Emperor Michael VII Doukas) and from their own fertile imaginations. Le livre et la vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre is a French treatment of Archpriest Leo’s Historia de preliis Alexandri Magni.

Another Alexander romance with a particularly juicy dragon treatment is Les faize d’Alexandre, a French translation of the Historia Alexandri Magni done by Vasco da Lucena for Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, between 1468 and 1475. It didn’t make the Medieval Manuscripts blog entry, but its author, Sarah J. Biggs, has been tweeting additional dragons today and one from Les faize d’Alexandre is a stand-out:

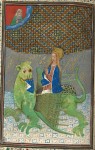

Who is that lady in bed with the dragon while a crowned man watches? That is Olympias, mother of Alexander, and the dragon is his real daddy. The voyeur is his, let’s just say adoptive, father Philip II of Macedon. This is what happens when the first two books of an ancient source go missing. Things get a tad fanciful and that version spreads far and wide. The Medieval Alexander romances all start with a dragon impregnating Olympias. There’s a less naughty version in the Le livre et la vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre where the dragon is just flying in through the window rather than actively making out with her.

Here’s the story in a nutshell. Egyptian pharaoh and sorcerer Neptanabus takes refuge in Macedonia after the gods tell him he’s about to be defeated by the Persian king Ochus. He bills himself as an astrologer and becomes a regular at court while the king is abroad fighting. Neptanabus becomes infatuated with Olympias and conceives a cunning plan to get in her bed through deception. He tells her the god Ammon will soon come to her chambers and together they will conceive a child. He then either changes himself into a dragon or tricks her into thinking he’s a dragon (there is some variety in the retelling) and they have sex, Olympias certain the whole time that she’s being impregnated by the god Ammon.

Here’s the story in a nutshell. Egyptian pharaoh and sorcerer Neptanabus takes refuge in Macedonia after the gods tell him he’s about to be defeated by the Persian king Ochus. He bills himself as an astrologer and becomes a regular at court while the king is abroad fighting. Neptanabus becomes infatuated with Olympias and conceives a cunning plan to get in her bed through deception. He tells her the god Ammon will soon come to her chambers and together they will conceive a child. He then either changes himself into a dragon or tricks her into thinking he’s a dragon (there is some variety in the retelling) and they have sex, Olympias certain the whole time that she’s being impregnated by the god Ammon.

Neptanabus then sends Philip a dream about Ammon getting his wife pregnant, so when he returns he’ll accept the demi-god foster son rather than, say, slaughter the baby and his mother for her adultery. Philip isn’t happy about it, but he takes it. Later magical occurrences confirm the accuracy of the prophecy, and so little Alexander is set on his path to greatness.

He does eventually find out about the deception. Alexander is 12 years old and doing military maneuvers when he playfully pushes Neptanabus into a ditch and breaks his neck. As any smartass would, Alexander tells Neptanabus he should have known that was going to happen,. The pharaoh replies that nobody can avoid their fate, and that his fate was to be killed by his own son. He then explains the true circumstances of the conception. Alexander takes it improbably well, as does Olympias. Alexander buries Neptanabus with all honors due a king, sorcerer, rapist, liar who conned his mother, father, country and himself into believing he was the son of a god.

Look at that dude caught his wife hooking up with a dragon!

Right? And the dragon is like “Ya, I’m hitting this. Deal with it.”

Hide yo kids, hide yo wives cuz dragons gettin’ errbody pregnant up here.

Terrific blog lesson today !! Thanks bunches! Love dragons, love manuscripts, this was heaven. 🙂

Alexander’s dragon dad looks suspiciously like a dog with fake wings. I think Phil was fooled.

Things that might also come to mind in relation to St. George and the dragon could be mythical dragon slayers like Theseus finishing off the Minotaur or Sigurd/ Sigismund -and all his incarnations- killing ‘the dragon’. – Apart from that, there was the ‘Order of the Dragon’ (Societas Draconistarum) founded in 1404 with members like Vlad II Dracul, his son Vlad III Dracula or Oswald of Wolkenstein and allies like Henry V of England. Moreover, the ‘Order of St George’, Hungarian: Szent György Vitézei Lovagrend, is said to be the first secular chivalric order in the world (established by King Charles I of Hungary in 1326).

Sigismund, King of Hungary, when fighting off the Ottomans: “we and the faithful barons and magnates of our kingdom shall bear and have, and do choose and agree to wear and bear, in the manner of society, the sign or effigy of the Dragon incurved into the form of a circle, its tail winding around its neck, divided through the middle of its back along its length from the top of its head right to the tip of its tail, with blood forming a red cross flowing out into the interior of the cleft by a white crack, untouched by blood, just as and in the same way that those who fight under the banner of the glorious martyr St George are accustomed to bear a red cross on a white field…”

See, Olympias, this is what happens when you wear your crown to bed.

I wonder if that dragon-in-the-boudoir illustration was as hilarious in the 15th century as it appears to us today. I’d like to think so!

a new plot line for Game of Thrones and perhaps the ay to tame a dragon