After years of negotiations, the City of Gothenburg in southwestern Sweden has agreed to return its collection of 89 textiles from the Paracas peninsula to Peru. The 2,000-year-old textiles are in extremely fragile condition, so they will be repatriated in phases. The first four pieces arrive in Peru next week and will be unveiled on June 18th. The rest will be transported over the course of seven years until the whole collection is returned by 2021.

After years of negotiations, the City of Gothenburg in southwestern Sweden has agreed to return its collection of 89 textiles from the Paracas peninsula to Peru. The 2,000-year-old textiles are in extremely fragile condition, so they will be repatriated in phases. The first four pieces arrive in Peru next week and will be unveiled on June 18th. The rest will be transported over the course of seven years until the whole collection is returned by 2021.

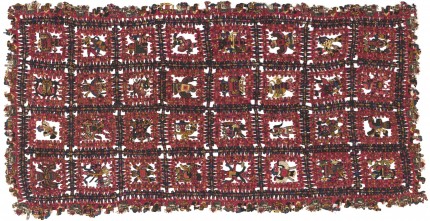

These extraordinary embroidered textiles first came to archaeologists’ attention in the early 20th century when they began to appear in private collections. Their intensity of color, size, design and composition were unique, unlike any textiles from known Peruvian cultures. Realizing that the textiles had to have been looted from an unknown site, Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello hired professional looter Juan Quintana to guide him to the find spot in 1925. He led Tello to Paracas, a desert peninsula on the southern coast of Peru, where Tello’s team excavated the remains of a civilization that flourished from around 700 B.C. to the second century A.D. when it became assimilated into the Nazca culture.

These extraordinary embroidered textiles first came to archaeologists’ attention in the early 20th century when they began to appear in private collections. Their intensity of color, size, design and composition were unique, unlike any textiles from known Peruvian cultures. Realizing that the textiles had to have been looted from an unknown site, Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello hired professional looter Juan Quintana to guide him to the find spot in 1925. He led Tello to Paracas, a desert peninsula on the southern coast of Peru, where Tello’s team excavated the remains of a civilization that flourished from around 700 B.C. to the second century A.D. when it became assimilated into the Nazca culture.

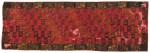

The people of the Paracas culture were able fishermen, farmers and craftspeople. They made obsidian tools, ceramics, hammered gold jewelry, basketry and most gloriously of all, complex and beautiful textiles. Made from the wool of camelids (llamas, alpacas and vicuñas) and cotton, the textiles were colored in more than 200 different bright shades using natural dyes. Every fabric was embroidered by hand with cactus thorn needles, and when you consider that textiles have been found that are 34 meters (112 feet) long, you can imagine what an incredibly labor-intensive process it was. Archaeologists believe it took years to produce a single such masterpiece.

The people of the Paracas culture were able fishermen, farmers and craftspeople. They made obsidian tools, ceramics, hammered gold jewelry, basketry and most gloriously of all, complex and beautiful textiles. Made from the wool of camelids (llamas, alpacas and vicuñas) and cotton, the textiles were colored in more than 200 different bright shades using natural dyes. Every fabric was embroidered by hand with cactus thorn needles, and when you consider that textiles have been found that are 34 meters (112 feet) long, you can imagine what an incredibly labor-intensive process it was. Archaeologists believe it took years to produce a single such masterpiece.

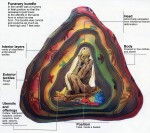

Creating such intricate and large textiles was a collaborative effort, the work of many people working at once. The textiles had important religious significance and indicated a person’s status in the community. The most exceptional examples were discovered by Tello on October 1st, 1927, when he encountered a vast funerary complex he named the Wari Kayan necropolis. There 429 people were found buried wrapped in layer after layer of textiles. The dead were adorned in their most prized possessions — jewelry, clothes, headbands — and seated in fetal position in a basket. Grave goods, food and sacrificial objects were added, and then the entire basket was wrapped in layers of fine embroidered textiles with a rough cotton cloth on the outermost layer. That’s why the large textiles were needed, because by the time they got to the outer layers, the bundles got big, as much as five feet high and seven feet wide.

Creating such intricate and large textiles was a collaborative effort, the work of many people working at once. The textiles had important religious significance and indicated a person’s status in the community. The most exceptional examples were discovered by Tello on October 1st, 1927, when he encountered a vast funerary complex he named the Wari Kayan necropolis. There 429 people were found buried wrapped in layer after layer of textiles. The dead were adorned in their most prized possessions — jewelry, clothes, headbands — and seated in fetal position in a basket. Grave goods, food and sacrificial objects were added, and then the entire basket was wrapped in layers of fine embroidered textiles with a rough cotton cloth on the outermost layer. That’s why the large textiles were needed, because by the time they got to the outer layers, the bundles got big, as much as five feet high and seven feet wide.

![]() When Tello unearthed these marvels, they had been kept in pristine condition by the arid desert climate and the lack of oxygen and light in the underground burials. As soon as they were excavated, the textiles started to degrade. All the Paracas finds were sent to museums in Lima for study and conservation. In 1930, the dictatorship of Augusto B. Leguía was overthrown in a military coup led by Lieutenant Colonel Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro. The subsequent social and political upheaval and war with Colombia left the Paracas textiles vulnerable to depredation. Looting and smuggling increased dramatically.

When Tello unearthed these marvels, they had been kept in pristine condition by the arid desert climate and the lack of oxygen and light in the underground burials. As soon as they were excavated, the textiles started to degrade. All the Paracas finds were sent to museums in Lima for study and conservation. In 1930, the dictatorship of Augusto B. Leguía was overthrown in a military coup led by Lieutenant Colonel Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro. The subsequent social and political upheaval and war with Colombia left the Paracas textiles vulnerable to depredation. Looting and smuggling increased dramatically.

It was during this chaos that 89 Paracas textiles found their way to Sweden. They were smuggled out of Peru in the early 1930s by Sven Karell, then the Swedish Consul General in Peru, who acquired them on the black market and shipped them back home into the appreciative arms of the Ethnographic Department of Gothenburg Museum. They went on display in November of 1932, but they were exposed to UV light, varying levels of heat and moisture, and repeated handling, all of which contributed to their decay.

It was during this chaos that 89 Paracas textiles found their way to Sweden. They were smuggled out of Peru in the early 1930s by Sven Karell, then the Swedish Consul General in Peru, who acquired them on the black market and shipped them back home into the appreciative arms of the Ethnographic Department of Gothenburg Museum. They went on display in November of 1932, but they were exposed to UV light, varying levels of heat and moisture, and repeated handling, all of which contributed to their decay.

In 1939 the museum was renovated. To prepare for their new exhibition, the Paracas textiles were sewn onto linen or dyed cotton and framed in glass. In 1963 the textiles were mounted vertically onto panels that could be pulled out. This turned out to be a disaster, as the vibrations from the pulling out damaged the increasingly delicate pieces. Finally in 1970 the textiles were taken out of public view. The museum moved to a new building in 1992, by which time the textiles had been installed in custom-built display cases. Then the Paracas collection moved again in 2001, this time to the Museum of World Culture. Because the fibers were in such poor condition, the textiles were moved on air suspended truck.

In 1939 the museum was renovated. To prepare for their new exhibition, the Paracas textiles were sewn onto linen or dyed cotton and framed in glass. In 1963 the textiles were mounted vertically onto panels that could be pulled out. This turned out to be a disaster, as the vibrations from the pulling out damaged the increasingly delicate pieces. Finally in 1970 the textiles were taken out of public view. The museum moved to a new building in 1992, by which time the textiles had been installed in custom-built display cases. Then the Paracas collection moved again in 2001, this time to the Museum of World Culture. Because the fibers were in such poor condition, the textiles were moved on air suspended truck.

They remained out of view until 2008, when after careful analysis the textiles which were found to be able to withstand movement were put on display. They were laid out horizontally and transported the short distance from the archives to the Museum of World Culture in vibration-free cases. A crane lifted them into the gallery through a window. The exhibition ran for three years. When the textiles returned to the museum archives, there was more fiber damage even with nothing but the utmost of caution employed in their transportation and display.

They remained out of view until 2008, when after careful analysis the textiles which were found to be able to withstand movement were put on display. They were laid out horizontally and transported the short distance from the archives to the Museum of World Culture in vibration-free cases. A crane lifted them into the gallery through a window. The exhibition ran for three years. When the textiles returned to the museum archives, there was more fiber damage even with nothing but the utmost of caution employed in their transportation and display.

It was that 2008 exhibition that spurred the repatriation talks. Not only did the museum not deny that the textiles had been smuggled by the Consul General, the exhibition was entitled A Stolen World and detailed the whole saga without flinching. It’s quite remarkable, really. I’ve never seen a museum so directly confront its complicity in the traffic in looted antiquities. Peruse the museum’s dedicated Paracas website to see how they handle the issue and to view some exquisite photographs of the collection.

It was that 2008 exhibition that spurred the repatriation talks. Not only did the museum not deny that the textiles had been smuggled by the Consul General, the exhibition was entitled A Stolen World and detailed the whole saga without flinching. It’s quite remarkable, really. I’ve never seen a museum so directly confront its complicity in the traffic in looted antiquities. Peruse the museum’s dedicated Paracas website to see how they handle the issue and to view some exquisite photographs of the collection.

In December of 2009, Peru contacted the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs formally requesting the return of the purloined Paracas textiles. Since the museum had just opened an exhibition whose catalog included copies of the letters between Karell and the Gothenburg Museum officials overtly plotting the receipt of stolen goods, there was none of the usual nonsense about “good faith” and “anonymous Swiss collections.” Peru’s legal right was undisputed. The main question was whether the textiles could stand transportation across the globe when they could barely stand to be transported a mile or so from storage to the display galleries.

In December of 2009, Peru contacted the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs formally requesting the return of the purloined Paracas textiles. Since the museum had just opened an exhibition whose catalog included copies of the letters between Karell and the Gothenburg Museum officials overtly plotting the receipt of stolen goods, there was none of the usual nonsense about “good faith” and “anonymous Swiss collections.” Peru’s legal right was undisputed. The main question was whether the textiles could stand transportation across the globe when they could barely stand to be transported a mile or so from storage to the display galleries.

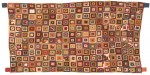

Now those issues have been dealt with as responsibly as possible, and the first four Paracas textiles are on their way home. One of them is a particularly exceptional example, a cloak about 104 by 53 centimeters made of squares with 32 different figures of animals, humans, plants and tools. Paracas textiles usually employ single motifs repeated over and over, so this tiled design is unique. Archaeologists believe it represents the movement of time, like a gorgeously embroidered Advent calendar. According to the felicitously named Luis Jaime Castillo Butters, Peru’s Vice Minister of Cultural Patrimony, the Paracas calendar textile is “the most important textile from Peru and one of the most important in the world.”

Now those issues have been dealt with as responsibly as possible, and the first four Paracas textiles are on their way home. One of them is a particularly exceptional example, a cloak about 104 by 53 centimeters made of squares with 32 different figures of animals, humans, plants and tools. Paracas textiles usually employ single motifs repeated over and over, so this tiled design is unique. Archaeologists believe it represents the movement of time, like a gorgeously embroidered Advent calendar. According to the felicitously named Luis Jaime Castillo Butters, Peru’s Vice Minister of Cultural Patrimony, the Paracas calendar textile is “the most important textile from Peru and one of the most important in the world.”

No disrespect meant, but after seeing the funeral bundle illustration, I’ll never look at a Hershey’s kisses with almond the same again. 😮

Sounds like the Swedish Consul-General’s action saved these textiles from certain destruction in the Peru of the 1930’s.

The Mantle with squares reminds me a lot of a painting called Color Study by Wassily Kandinskiy (1913). He used circles inside the squares, but it seems like 2000 years ago there was a huge attraction to circles.

http://uploads3.wikiart.org/images/wassily-kandinsky/color-study-squares-with-concentric-circles-1913(1).jpg

Thank you! These textiles are simply astounding. Yet another great example of the out-of-nowhere wonders that regularly show up on this blog.

Livius, given your obsession with high-quality photos, you must have been giddy with delight over the detail in these!