Forensic studies on the skeletal remains of Pharaoh Senebkay discovered last year at Abydos have found numerous sharp-force injuries indicating that he died a brutal death in battle. A pharaoh from a weak transitional dynasty in Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period (1650 and 1550 B.C.), Senebkay was beset by enemies to the north — the Canaanite Hyksos 15th Dynasty — and south — the Theban 16th and 17th Dynasties (1650 – 1590 B.C., 1580 – 1550 B.C.). These were turbulent times that would only come to end with the unification of Egypt under Pharaoh Ahmose I, founder of the 18th Dynasty and of the New Kingdom.

Forensic studies on the skeletal remains of Pharaoh Senebkay discovered last year at Abydos have found numerous sharp-force injuries indicating that he died a brutal death in battle. A pharaoh from a weak transitional dynasty in Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period (1650 and 1550 B.C.), Senebkay was beset by enemies to the north — the Canaanite Hyksos 15th Dynasty — and south — the Theban 16th and 17th Dynasties (1650 – 1590 B.C., 1580 – 1550 B.C.). These were turbulent times that would only come to end with the unification of Egypt under Pharaoh Ahmose I, founder of the 18th Dynasty and of the New Kingdom.

Senebkay lived somewhere in the middle of the Second Intermediate Period, probably around 1600 B.C., which makes him the earliest pharaoh known to have died in battle. Before this study the first pharaoh thought to have died in battle was Theban Pharaoh Seqnenre of the 17th Dynasty (ca. 1558 B.C.), father of the future Ahmose I. Although Seqnenre too was viciously slaughtered, there are no defensive wounds so he could well have been attacked in his sleep or executed by his Hyksos enemies.

Osteologists found that Senebkay was between 35 to 49 years old at the time of his death and of unusual height for his era at five feet seven inches to six feet tall. His wounds were so extensive he must have been the target of multiple attackers.

Osteologists found that Senebkay was between 35 to 49 years old at the time of his death and of unusual height for his era at five feet seven inches to six feet tall. His wounds were so extensive he must have been the target of multiple attackers.

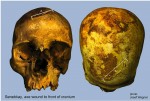

The king’s skeleton has an astounding eighteen wounds that penetrated to the bone. The trauma includes major cuts to his feet, ankles, knees, hands, and lower back. Three major blows to Senebkay’s skull preserve the distinctive size and curvature of battle axes used during Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period. This evidence indicates the king died violently during a military confrontation, or in an ambush.

The weapon in question was a bronze duckbill axe. University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Josef Wegner, leader of the excavation team, believes the pharoah’s injuries, the weapons they were inflicted with and force with which they were used indicates professional soldiers took the king down in a fight rather than, say, assassins or muggers.

The weapon in question was a bronze duckbill axe. University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Josef Wegner, leader of the excavation team, believes the pharoah’s injuries, the weapons they were inflicted with and force with which they were used indicates professional soldiers took the king down in a fight rather than, say, assassins or muggers.

Senebkay appears to have been on horseback when the assault began. Wounds to his lower body — a cut to his right ankle so severe it would have all but amputed his foot, slashes on his knees and hands — were inflicted from the ground upwards and the strikes on his lower back indicate he was seated when he received them. That was more than enough to unhorse him. By the time his assailants embedded their axes in his skull, the pharaoh was probably on the ground.

Another surprising result of the osteological analysis is that muscle attachments on Senebkay’s femurs and pelvis indicate he spent a significant amount of his adult life as a horse rider. Another king’s body discovered this year in a tomb close to that of Senebkay also shows evidence for horse riding, suggesting these Second Intermediate Period kings buried at Abydos were accomplished horsemen.

This is a significant discovery because the introduction of the horse to Egypt was still recent at the time. The first inscriptions referring to the use of horses among the Egyptian elite appear shortly after this period and the chariots that would become inextricably associated with pharaonic Egypt weren’t introduced until the New Kingdom.

One of other skeletons thought to be from a royal tomb (other than Senebkay’s, none of the seven other royal tombs had cartouches identifying the deceased), was a powerfully built man trained to perform a strenuous, repetitive activity with his left arm, possibly archery or combat. Between their prowess on horseback and their tough physical training, it’s possible these Abydos pharaohs were warrior-kings. The research team is hoping to be able to confirm with DNA testing if any of the people found buried in the tombs bore a familial relationship to each other.

One of other skeletons thought to be from a royal tomb (other than Senebkay’s, none of the seven other royal tombs had cartouches identifying the deceased), was a powerfully built man trained to perform a strenuous, repetitive activity with his left arm, possibly archery or combat. Between their prowess on horseback and their tough physical training, it’s possible these Abydos pharaohs were warrior-kings. The research team is hoping to be able to confirm with DNA testing if any of the people found buried in the tombs bore a familial relationship to each other.

Because we know so little about the Abydos kings, the geographic boundaries of their territory are unclear. It seems Senebkay did not die close to Abydos, however. The linen bandages wrapping him are close to the bones, which means the body had already been decaying for a while when he was mummified. He could have been exposed, perhaps by the enemies who killed him, before being sent home, or the voyage home was so long it took several weeks to get his decomposing body to the royal necropolis at Abydos.

Possibly the king died in battle fighting against the Hyksos kings who at that time ruled northern Egypt from their capital at Avaris in the Nile Delta. However, Senebkay may have died in struggles against enemies in the south of Egypt. Historical records dating to Senebkay’s lifetime record at least one attempted invasion of Upper Egypt by a large military force from Nubia to the south. Alternatively, Senebkay may have had other political opponents, possibly kings based at Thebes.

The University of Pennsylvania team will continue excavations at Abydos and to study the remains in the hope of answering some of these questions.

I’m interested in the Negroid features of the skull. Often racial claims about the ancient Egyptians have a less than convincing they-lived-in-Africa-so-they-were-Black reasoning behind them, but judging from the eye sockets, the wide bridge to the nose, and what I can see of the upper jaw, we do have a Black pharaoh here.

Skull features of in particular Egyptian Pharaos should probably be handled with care. Of which colour -would you say- are people like e.g. Mariah Carey ? A mix of people from ‘far south’ and ‘the northeast’ in northern Africa is actually no real surprise. Have a look at Tiye, mother of Akhenaten and Tut’s own nanna.

What a pity that there is no view at the skull from the LEFT side, where apparently something cracked his frontal bone. The wound revealed by the TOP view, the one that is marked on the left with an ‘A’, however, seems to be the blunt impact of a club. Unsure if a stone axe could possibly have done it, this does not look like a cut at all. The marks at his ankle and knee, of course, are clear cuts.

Indeed, he seems to have been attacked by foot soldiers, successfully unhorsed (dehorsed ?) and then finished off, maybe similar to a light armoured medieval knight under attack by revolting peasants or foot soldiers without bows and arrows. His legs might have been indeed unprotected.

Fascinating! Started looking at other pharaohs online after reading this and apparently there is a lot of controversy over whether Ramesses II was red-haired or not!

I didn’t realize it was still a controversy. I thought they’d found he was indeed a natural redhead by examining hairs under a microscope.

Fascinating. I was very surprised to read about the riding, which is indeed the only thing that makes sense considering the injuries.

I’ve read enough about ancient Egypt to know horses were not used in the Old and Middle Kingdom and the elite fought from chariots in the New Kingdom. However, the intermediate times were troubled eras which saw a lot of fighting and a lot of influence from outside Egypt.

Oh, and to reply to John Cooper, I don’t know about this pharaoh, it’s probably more difficult to tell, like soph wrote (and based on information from other periods of ancient Egypt, I’d say this dynasty had its power base too far north to assume they were black). However, there was certainly a dynasty of black pharaohs in the late period (the 25th dynasty, originally from Nubia)

I love it when archaeologists can capture transitional moments. It stands to reason that somewhere in between no horses and the development of chariot technology there were accomplished horsemen. It even makes sense that there’s been no art found thus far documenting this transition because the Abydos kings had very rudimentary decoration on their tombs.

There is a lot of discussion in the circles of those studying medieval sword techniques about modes of attack. Feet, ankles, knees and upper legs were common targets whether the individual was on foot or mounted. A crippling leg injury pretty much puts paid to one’s ability to fight rendering even the best armored soldier vulnerable. Low back attacks also fits this bill. So in light of that it might call into question whether he was mounted at all but was on foot. Hammering away at a mounted man’s legs won’t necessarily unhorse him, but it would bring down someone on foot. The low back would be difficult to reach at all if a man were mounted, but not so with a man on foot.

I would wager in that our late King was on foot, or maybe in a chariot and not horseborne.