I’m asking for a friend. (The British Library is my friend, right?) On display at the British Library’s Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy exhibition is a medieval double-edged sword made of steel with an inlaid gold wire inscription on one side. The inscription appears to read:

I’m asking for a friend. (The British Library is my friend, right?) On display at the British Library’s Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy exhibition is a medieval double-edged sword made of steel with an inlaid gold wire inscription on one side. The inscription appears to read:

Experts haven’t been able to decipher this mysterious assortment of letters, so the British Library’s phenomenal Medieval Manuscripts blog is opening up the floor to the Internet. Some think it was a religious dedication of some kind using the first initials of words. There are inscribed crosses on the other side and an inlaid crescent near the point on both sides which may be the maker’s mark.

The sword was discovered in the River Witham, Lincolnshire, in July of 1825 by workers widening and deepening the river just below the lock to make room for larger vessels. The Bishop of Lincoln gave the sword to the Royal Archaeological Institute which in 1858 donated it to the British Museum. It dates to around 1250-1330 and has a straight cross guard with a wheel-shaped pommel atop the grip. Weighing 2 lb 10 oz and measuring 38 inches long, the sword was a killer, capable of cleaving a man’s skull in two.

The sword was discovered in the River Witham, Lincolnshire, in July of 1825 by workers widening and deepening the river just below the lock to make room for larger vessels. The Bishop of Lincoln gave the sword to the Royal Archaeological Institute which in 1858 donated it to the British Museum. It dates to around 1250-1330 and has a straight cross guard with a wheel-shaped pommel atop the grip. Weighing 2 lb 10 oz and measuring 38 inches long, the sword was a killer, capable of cleaving a man’s skull in two.

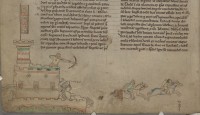

This kind of sword was a classic knightly weapon of the 13th century and is depicted in many an effigy and illustration. Here’s an example from the British Library’s 14th century illuminated manuscript of the Grandes Chroniques de France in which French knights besiege Rouen in 1203/1204 during King Philip Augustus’ invasion of Normandy.

In fact, the sword was believed to have a very close connection to French knights from that turbulent period. When the sword was first discovered, workers found other armature — swords, daggers, chain mail — in the muck of the riverbed leading to speculation that these were the remains of French knights who had drowned in the river after the Second Battle of Lincoln in 1217. When the First Barons’ War broke out between King John and his nobles in 1215 after John refused to abide by the terms of Magna Carta, the barons invited Prince Louis of France to take the throne of England. He accepted and turned up with an army in May of 1216. Louis waltzed into London unopposed and was proclaimed king in a ceremony at St. Paul’s Cathedral. He doesn’t make the official king list because he was never crowned, but for a while in 1216-1217 the Dauphin of France actively occupied half of England.

In fact, the sword was believed to have a very close connection to French knights from that turbulent period. When the sword was first discovered, workers found other armature — swords, daggers, chain mail — in the muck of the riverbed leading to speculation that these were the remains of French knights who had drowned in the river after the Second Battle of Lincoln in 1217. When the First Barons’ War broke out between King John and his nobles in 1215 after John refused to abide by the terms of Magna Carta, the barons invited Prince Louis of France to take the throne of England. He accepted and turned up with an army in May of 1216. Louis waltzed into London unopposed and was proclaimed king in a ceremony at St. Paul’s Cathedral. He doesn’t make the official king list because he was never crowned, but for a while in 1216-1217 the Dauphin of France actively occupied half of England.

The tide turned when King John died in October of 1216. Even though John’s son Henry was only nine years old, barons who had sided with Louis switched sides in droves. William Marshal, “the greatest knight that ever lived,” was Henry’s regent and fought at the head of his army, drawing more knights to abandon Louis for Henry. On May 20th, 1217, forces loyal to the nine-year-old King Henry III of England attacked the city of Lincoln, then held by the French. The English held Lincoln Castle, however, so while Marshall’s army took the north gate of the city, Falkes de Breauté deployed his crack crossbowmen along the castle ramparts to rain a hellfire of bolts into the French occupiers. It was a rout, followed by a very thorough pillaging of the city that has gone down in history as the Lincoln Fair. French knights who weren’t killed or captured fled, some of them sailing down the Witham. Some of the ships, laden with men, arms and armour, sank drowning the flower of French chivalry and, ostensibly, leaving their stuff behind for canal diggers to find 600 years later.

The tide turned when King John died in October of 1216. Even though John’s son Henry was only nine years old, barons who had sided with Louis switched sides in droves. William Marshal, “the greatest knight that ever lived,” was Henry’s regent and fought at the head of his army, drawing more knights to abandon Louis for Henry. On May 20th, 1217, forces loyal to the nine-year-old King Henry III of England attacked the city of Lincoln, then held by the French. The English held Lincoln Castle, however, so while Marshall’s army took the north gate of the city, Falkes de Breauté deployed his crack crossbowmen along the castle ramparts to rain a hellfire of bolts into the French occupiers. It was a rout, followed by a very thorough pillaging of the city that has gone down in history as the Lincoln Fair. French knights who weren’t killed or captured fled, some of them sailing down the Witham. Some of the ships, laden with men, arms and armour, sank drowning the flower of French chivalry and, ostensibly, leaving their stuff behind for canal diggers to find 600 years later.

Without identifying marks connected to specific knights, this story is impossible to prove. Still, the design and period of the sword make it relevant as a weapon very much like those used during the battles between the English crown and its unruly barons. It’s neat to think that it may even go a step further and be an actually relict of the First Barons’ War.

If you have any ideas about what the inscription might mean, join the party in the comments on the Medieval Manuscripts blog entry where smart people are saying smart things.

Perhaps it’s the initials for the Middle-English version of “This Side Toward Enemy.” ^___^

It’s medieval scrabble.

I immediately thought of Ulberht swords. I’m neither a Viking scholar nor a medievalist, though.

Apparently, there’s more swords with mystery inscriptions from the area…

http://www.bostontarget.co.uk/Magic-swords-River-Witham-display-Boston-s/story-16668870-detail/story.html

There’s something odd about the letters. I’ve been looking at it for a while now…

The two Rs are completely different and the W seems like it shouldn’t be there at all…

Maybe the inscription was added after it was found?

In medieval times not many could read, except for monks and nobles, the rest were pretty much illiterates. Even though the bible was quite widespread it was often written in latin and the common people had to go to church and listen to the priests read from it… which didn’t really matter since no one knew latin :facepalm:

I’m guessing that this writing is mostly gibberish added to the blade by someone trying to increase their status: “Look at me! I’m educated! I know letters and stuff! 😎 ”

Since it seems that someone has added crusader symbols and fake latin, and a tiny half moon at the tip.

It somewhat resembles roman numbers, though everything is wrong and makes no sense.

At the same time the golden engraving is to well preserved, this blade does not seem to have been wielded since it was decorated. Perhaps a souvenir of sort to commemorate a travel/part of the crusade to the holy land? 🙂

++ :confused:

… ok, that was REALLY cryptic.

+YMRAEHTNIOJ+

If it’s a French knight’s sword… Anyone tried French on this? But I can’t get much past ND as “Notre Dame” :confused:

I think it’s obviously an ancient form of the “Has Anyone Really Been Far Even as Decided to Use Even Go Want to do Look More Like?”

😮

with the ‘X’s as word separators: “By Our Lord, this Sword belongs to Orvi”.

I think it’s interesting that it weighs less than 3 pounds. Oh, but medieval swords were soooo HEAVY! Like, barely liftable by ordinary people!

I just want to know why a knight would have *wanted* to carry a twenty pound sword when a 3 pound one could cleave his enemy’s skull nicely and not wear him out in the process. Silly misconceptions …

At the beginning could ND be Nomine Deum, for the rest of it try either the canon of the Mass or relevant prayer or invocation of the period.

Following up on this suggestion, could the “X” indicate the Greek initial (Chi) for “Christ”.

might then the beginning be “Nostre Domine Christus” – “Our Lord Christ…”?

Well if it is a french (owned) sword then I think it reads “I surrender”…

Mabey dates in Roman nurmerals and inetials?

cyrrilic?

(Translated: “putin killed me”)

There is only one “r”. The symbol after the D

appears to be something else, like a lower case n

This site is excellent for deciphering other engraved swords. Similar words found on this sword: http://polisharms.com/zbaszyngladius/

According to: http://polisharms.com/zbaszyngladius/ …

cross-shaped signs, made before, and behind an inscription on sword 1 indicate that the inscription is complete. The inscription is probably made in Roman majuscule, and is probably Latin. +NDXOXCHWDRGHDXORVI+: ND = N(omine) D(omini), (X)ristus ?, C or CH = C(hristi)?. You get the idea. Some swords had abbreviated psalms. Google sword inscriptions and further assistance.

It is to bad that this excellent blog draws attention from so manny naive persons.Yes, I’m from Europe.

Speaking of naive, I just held it up to a mirror, thinking, …. well maybe, lol

You’re the odd one out here, you non imaginative twat :hattip:

the middle section ie CHWDRGHD has a hint of welsh about it, but no partic word comes to mind. if the Xs are spaces between words then ORVI could be a name. but if this item was left in 13th Cent. lincs, then there wouldnt’ve been much of a celtic presence there by then.

I know what you mean. I’m thinking the sword was created 1200s but inscribed 1400s for King Henry VI. Encrypted because he was on a special mission. It was the time of the war of the roses. So maybe they were agents of the King sent North with a message. Maybe they were on a spying mission. But I also think their may have been an Emperor in the 12CE. I will check him out.

The Crusader symbolic crosses could have been an invocation of the spirit of the people who won France for England when the sword was made.

ND = By our God

X = seperator

O = This, my, our

X = seperator

CHWDR = chowder

GHD = good/best

X = seperator

Orvi = (latin), orbi, world

So, the sword’s inscription reads: “By God, my chowder’s the goodest (best) in the world” … or something like that.

I vision the first and last symbols as Templar crosses and the marks notating the “beginning and the end” If you notice them they face opposite could this mean that the rule of the church is over and that the rule by the people has begun?

X is random, the letters is the first name of the people it killed

to Catherine, an intriguing idea. the year 1400 jumps out so could we amend your theory slightly and place it during the Glyndwr [Glendower] rebellion? either a message to, or from him? possibly heading to or from the coast to France?

The dialect is very simler maltese