Turkish archaeologists have discovered an ancient mosaic in the remains of a house from the 3rd century that features a skeleton enjoying a large loaf of bread and pitcher of wine. It was found in 2012 in Turkey’s southernmost state, Hatay Province, in the provincial capital of Antakya, (Antioch in antiquity) during construction of a cable car system.

Turkish archaeologists have discovered an ancient mosaic in the remains of a house from the 3rd century that features a skeleton enjoying a large loaf of bread and pitcher of wine. It was found in 2012 in Turkey’s southernmost state, Hatay Province, in the provincial capital of Antakya, (Antioch in antiquity) during construction of a cable car system.

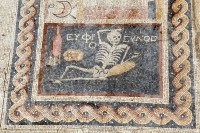

It is believed to have been the emblema, the elaborate centerpiece of a mosaic floor, in the triclinium (dining room) of an elegant villa. There are three  scenes inside a rectangle with a woven guilloche border. On one end is missing a large section but the head and arms of a servant carrying a flame are visible. This represents the heating of the bath. The middle scene is almost intact and depicts two men moving towards a sundial on a column. The leader is a young man who was of some rank in the household, the son of the owner, perhaps, while the his manservant or butler follows. The sundial is set to between 9:00 and 10:00 PM and the text refers to him being late for dinner. The last panel has the recumbent skeleton, holding a drinking cup in one hand, his other arm thrown casually over his head, two loaves of bread and a wine amphora by his side. The motto “Be cheerful and live your life” is written on both sides of his head.

scenes inside a rectangle with a woven guilloche border. On one end is missing a large section but the head and arms of a servant carrying a flame are visible. This represents the heating of the bath. The middle scene is almost intact and depicts two men moving towards a sundial on a column. The leader is a young man who was of some rank in the household, the son of the owner, perhaps, while the his manservant or butler follows. The sundial is set to between 9:00 and 10:00 PM and the text refers to him being late for dinner. The last panel has the recumbent skeleton, holding a drinking cup in one hand, his other arm thrown casually over his head, two loaves of bread and a wine amphora by his side. The motto “Be cheerful and live your life” is written on both sides of his head.

(Writer İlber Ortaylı disputes the eat, drink and be merry interpretation. He reads it as “You get the pleasure of the food you eat hastily with death” and thinks the structure was not a private home of a wealthy person, but a sort of soup kitchen trying to hustle people out the door as quickly as possible.)

There’s some confusion over the date of the mosaic. The first article about the find that I read said it was from the 3rd century, which means A.D., but later stories by the same press outlet date it to the 3rd century B.C. That in turn has been picked up by the international press. Greek was spoken and written by the elites in both periods, so the words are of no particular help.

This one says “Hatay is known for its Roman-era mosaics dating back to the second and third centuries BCE,” but those are not Roman dates. Antioch was founded by Alexander the Great’s general Seleucus I Nicator in 300 B.C. and was ruled by Seleucid monarchs until 64 B.C. when it was absorbed into the Roman Syrian province as a free city.

It doesn’t seem likely to me that this mosaic was created in the early years of the Seleucid monarchy. I think this is a Roman-era mosaic, because of its glass tesserae, the theme, look and quality of the piece. Indeed, Demet Kara, the Hatay Archaeology Museum archaeologist who provides the date in all the articles, compares the Antioch mosaic to other skeleton mosaics in Italy and those are unquestionably Roman.

It doesn’t seem likely to me that this mosaic was created in the early years of the Seleucid monarchy. I think this is a Roman-era mosaic, because of its glass tesserae, the theme, look and quality of the piece. Indeed, Demet Kara, the Hatay Archaeology Museum archaeologist who provides the date in all the articles, compares the Antioch mosaic to other skeleton mosaics in Italy and those are unquestionably Roman.

While the theme of a skeleton or skull representing the inevitability of death was Hellenistic, the Romans developed it further in their art. They were fond of a skeleton partying with  them in the dining room. There are several extant drinking, eating and reclining mosaics from the 1st century found at Pompeii and in Rome. The glorious Boscoreale treasure, a silver dining set buried before the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D., has two silver cups embossed with the skeletons of philosophers and engraved with Epicurean sayings like “Enjoy life while you can, for tomorrow is uncertain.” The cups, like the skeleton mosaics, were meant to remind diners of the fleeting nature of life and the importance of enjoying the moment, a relevant message for a room dedicated to the gustatory pleasures.

them in the dining room. There are several extant drinking, eating and reclining mosaics from the 1st century found at Pompeii and in Rome. The glorious Boscoreale treasure, a silver dining set buried before the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D., has two silver cups embossed with the skeletons of philosophers and engraved with Epicurean sayings like “Enjoy life while you can, for tomorrow is uncertain.” The cups, like the skeleton mosaics, were meant to remind diners of the fleeting nature of life and the importance of enjoying the moment, a relevant message for a room dedicated to the gustatory pleasures.

A large number of mosaics of exceptional quality have been found in Antakya because Antioch was an important city for centuries. In the Early Roman period, it was the third largest city in the world after Rome and Alexandria. The homes of wealthy and influential people were decorated at great expense with the best floor art money could buy. Antioch had its own mosaic schools and workshops that were internationally renown. Roman Antioch was replete with top notch mosaics.

Hatay’s mayor, Lütfi Savaş, has visions of tourism plums dancing in his head. Just this February he helped launch the Mosaic Road Project to promote four cities in the province that are rich in Greek and Roman-era mosaics — Hatay, Gaziantep, Kahramanmaraş and Şanlıurfa — as desirable tourist destinations. The plan is to build an archaeological park in Hatay, scheduled for completion in 2017, and to house the mosaics in a dedicated museum. Ortaylı thinks the skeleton mosaic should remain in situ and a new museum built on the site similar to Israel’s plan for the Lod mosaic.

Carpe diem – Loaves of bred with skeletons, or Dia De Los Muertos as it is known today in Mexico.

The whole thing might be a depiction of, beginning at the mainly disappeared right, ‘Birth or a slave assisting at birth’, ‘Rushing fro/to the bathhouses’ in the middle and ‘An unsure eternal -as the Romans would have said- Triclinium‘ on the left.

The inscriptions in the middle appear to be names, maybe indeed ‘being late for dinner’, whereas the ones on the left appear to be something like:

‘euthro’ / εὐτρο(φία) / nourishing condition

‘synos’ / συνο(σ/δ)ία / companionship on a journey

:skull:

Daww, they’re adorable! :love:

dead heads from a long time ago, another home-run, thank you so much for your efforts, you are a dear from whatever age.

I deleted your flood of oddness, Mc, as you said you’d keep going until I asked you to stop. So, yeah, stop, please.

down 2me last drink, a cider, sure happy2 to have followed this site 4many, many yeahs

I figured a bit of the ol’ demon liquor was involved. Thanks for following for so many years. Be safe!

luv the light tan, desert look, of the background here . . .

Yeah me too. That’s enough now, Mc. Sleep it off.

How can a sundial be set to between 9 and 10 PM? Wouldn’t the sun be down by then? Maybe he was late to breakfast? 😉

Also, I would be surprised if someone took the time and money to create such a beautiful and artistic mosaic floor for a soup kitchen. They’d have thought plain ol’ flat tiles would have sufficed for their poor soup-kitcheners.

I hope the mayor gets his wish and lots of tourists descend on the town to see these and other amazing mosaics.

To set a sundial place the sundial on a horizontal surface (hence the name, “horizontal sundial”) and align the gnomon with true north (on the dial face, 12 noon should point north). Morning times appear on the dial face to the left side of the meridian; afternoon times to the right.

So it’s quite easy for the mosaic artist (artistic licence) to represent anytime they wish to depict. After all a skeleton wouldn’t eat nor drink much either, would they?

Wonderful!!

Does it not say “ΕΥΦΡΟΣΥΝΟΣ” (“euphro-synos”, split by the skeleton), “euphoric”? How does it form “be cheerful and live your life”?

I agree. That is more on the lines of “[be] cheerful”, I guess the live your life is more of an added interpretation also in light perhaps of Epicurean phylosophy. There is a slightly more nuanced discussion on https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/a-different-view-on-hatays-skeleton-mosaic-104739

Hi, I just saw this article and i’m very interested in your claim , how do we know that the concept of skulls and the inevitability of death goes back to Hellenistic years?