A Roman fort built in London in the aftermath of the Boudiccan uprising is shedding new light on this little-known period in the development of the capital. The site, on the edge of the early town 750 feet or so northeast of Roman-era London Bridge, was excavated by experts from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) between 1997 and 2003. They found a fort built over the ruins of commercial and residential structures destroyed in the revolt of 60/61 A.D.

A Roman fort built in London in the aftermath of the Boudiccan uprising is shedding new light on this little-known period in the development of the capital. The site, on the edge of the early town 750 feet or so northeast of Roman-era London Bridge, was excavated by experts from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) between 1997 and 2003. They found a fort built over the ruins of commercial and residential structures destroyed in the revolt of 60/61 A.D.

Londinium was still a smaller city at the time of the uprising. It was founded after the Roman conquest of 43 A.D. so it was less than 20 years old and wasn’t an official colony yet when it fell to Boudicca. Thanks to the Thames and its direct line to maritime trade, Londinium was a growing concern with enough wealth to make it an appealing target for the Iceni. When he realized they were coming, the governor of Britannia, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, decided his scant troops could not successfully defend the city so it was better to sacrifice London and live to fight another day. He left, taking his army with him and the residents to the not-so-tender mercies of Boudicca. From Tacitus’ Annals 14:33:

Those who were chained to the spot by the weakness of their sex, or the infirmity of age, or the attractions of the place, were cut off by the enemy. Like ruin fell on the town of Verulamium, for the barbarians, who delighted in plunder and were indifferent to all else, passed by the fortresses with military garrisons, and attacked whatever offered most wealth to the spoiler, and was unsafe for defence. About seventy thousand citizens and allies, it appeared, fell in the places which I have mentioned. For it was not on making prisoners and selling them, or on any of the barter of war, that the enemy was bent, but on slaughter, on the gibbet, the fire and the cross, like men soon about to pay the penalty, and meanwhile snatching at instant vengeance.

Londinium was devastated. It was still in ruins in around 63 A.D. when the fort was built. It’s likely the fort’s aim wasn’t solely defense, but also to serve as a base for reconstruction efforts. From its size, it would have held between 500 and 800 soldiers.

Londinium was devastated. It was still in ruins in around 63 A.D. when the fort was built. It’s likely the fort’s aim wasn’t solely defense, but also to serve as a base for reconstruction efforts. From its size, it would have held between 500 and 800 soldiers.

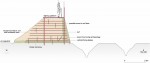

Our excavations at Plantation Place for British Land on Fenchurch Street in the City of London exposed a section of a rectangular fort that covered 3.7 acres. The timber and earthwork fort had 3 metre high banks reinforced with interlacing timbers and faced with turves and a timber wall. Running atop the bank was a ‘fighting platform’ fronted by a colossal palisade, with towers positioned at the corners of the gateways. This formidable structure was enclosed by double ditches, 1.9 and 3m deep, forming an impressive obstacle for would be attackers.

Archaeologists unearthed a number of military artifacts from the site — plate armor, spears, shields, harness fittings, a partial cavalry helmet — as well as construction tools including a pick axe and hammer. They also found evidence of roads, storage facilities, a granary, a latrine, cookhouse, etc. within the fort precinct. The barracks appear to have been tents, however, not permanent buildings, and the fort was only in active use for a decade. Unlike later forts, this one was a temporary installation meant to help rebuild the city and keep the residents secure.

Archaeologists unearthed a number of military artifacts from the site — plate armor, spears, shields, harness fittings, a partial cavalry helmet — as well as construction tools including a pick axe and hammer. They also found evidence of roads, storage facilities, a granary, a latrine, cookhouse, etc. within the fort precinct. The barracks appear to have been tents, however, not permanent buildings, and the fort was only in active use for a decade. Unlike later forts, this one was a temporary installation meant to help rebuild the city and keep the residents secure.

The fort is of great significant despite its impermanence because it is a strong indication that the Romans had picked Londinium to be the new capital. The previous provincial capital, Camulodunum, aka Colchester, does not appear to have had a similar fort built in the wake of its destruction by Boudicca. London was a practical choice. Unlike Colchester, London had easy access to the sea, ocean-going ships could go directly to the city via the Thames, and the city was new, not founded by potentially troublesome British tribes. Troops stationed at the fort provided much-needed labour and engineering expertise to rebuild roads, docks and buildings.

The fort is of great significant despite its impermanence because it is a strong indication that the Romans had picked Londinium to be the new capital. The previous provincial capital, Camulodunum, aka Colchester, does not appear to have had a similar fort built in the wake of its destruction by Boudicca. London was a practical choice. Unlike Colchester, London had easy access to the sea, ocean-going ships could go directly to the city via the Thames, and the city was new, not founded by potentially troublesome British tribes. Troops stationed at the fort provided much-needed labour and engineering expertise to rebuild roads, docks and buildings.

The Plantation Place fort was dismantled around 85 A.D. and the land it had occupied was built over with new development. Much of that was felled in the raging fire of 145 A.D., after which the area welcomed a new masonry townhouse. A hoard of gold coins was hidden in the basement around 174 A.D.

The Plantation Place fort was dismantled around 85 A.D. and the land it had occupied was built over with new development. Much of that was felled in the raging fire of 145 A.D., after which the area welcomed a new masonry townhouse. A hoard of gold coins was hidden in the basement around 174 A.D.

The full research on the Plantation Place fort has been published in An Early Roman Fort and Urban Development on Londinium’s Eastern Hill, now for sale in the museum shop and available for pre-order on Amazon.

How did Boudica ever become Boadicea, or vice versa?

A Roman “passus” equals 4.855643 ft. The standard Roman foot (“pes”) was usually about 295.7 mm (97 percent of today’s measurement), so 1.03 * 1 passus makes 5 “modern” feet.

One can only assume, however, if ‘Boadicea’, or whatever her real name might have been, was able to write her own name. Remarkably, some Celts wrote in Greek: βουδόκος=receiving oxen; δίκα=justice.

Tacitus and other Romans in return may have had their difficulties with locally spoken languages, maybe as Londoners from today might have difficulties with their Latin.

Tacitus himself apparently wrote of ‘Boudicca generis regii femina duce‘ – because in contrast to the Romans – neque enim sexum in imperiis discernunt.

I love this comment more than is decent. Thanks so much, Caligula Minus. :thanks:

Thanks for that. But what I meant was that when I was at primary school she was “Boadicea”. Always. Now she’s always Boudicca. How come? If the latter has the Tacitus stamp of approval, where did “Boadicea” come from? If “Boadicea” had been the term in English for decades, or centuries, as the case may be, why be fusspots and turn to Boudicca?

Still, the story hasn’t changed, perhaps because there was only one source for the story anyway.

On the other hand, there is I gather only one source for the story of King Canute and the tide, but much of the population believes a yarn that’s counter to that one source. And while we are at it, what sort of fusspots decreed he must be spelled Cnut? Given the propensities of schoolboys, they might at least have had the sense to insist on Knut.

Boadicea entered the English lexicon in the 17th century. It was a misprint of “Boadicia” in the 1624 edition of Polydore Vergil’s Anglica Historia. People weren’t overly concerned about spelling consistently back then, so there were several different versions floating about. Boadicea is probably the farthest from the Celtic original or the Latinized version. As for why the error stuck long enough to make it into your schoolbooks, who can say? I wouldn’t be surprised if it were something as simple as it looking cool.

Come to think of it, given the propensities of schoolboys, “Knut” might not work either.

This design is wicked! You obviously know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog well, almostHaHa! Wonderful job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool! afbebeggadcakced

Hello!