Burghead Fort near the town of Lossiemouth in Moray, northeastern Scotland, was a major power center in the early Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. Between 6th and 9th centuries, the promontory fort at the site of the modern town of Burghead dominated the region. It was the largest of its time, three times larger than any other fort in Scotland. It is also the oldest known Pictish fort.

Burghead Fort near the town of Lossiemouth in Moray, northeastern Scotland, was a major power center in the early Pictish kingdom of Fortriu. Between 6th and 9th centuries, the promontory fort at the site of the modern town of Burghead dominated the region. It was the largest of its time, three times larger than any other fort in Scotland. It is also the oldest known Pictish fort.

Its true origin and great historical significance wasn’t understood in the early 19th century. The fort was believed to be Roman, “the Ultima Ptoroton of Richard of Cirencester and Alta Castra of Ptolemy,” as Major-General William Roy labelled it in his drawing of the floor plan and sections of what was left of the fort in 1793. You might think that its purported Roman origin and association with the 2nd century writer Ptolemy who was believed to have described it in his Geography would be sufficient to ensure some degree of preservation, but you would be wrong. More than half of the fort’s surviving remains were destroyed when the town of Burghead was built between 1805 and 1809.

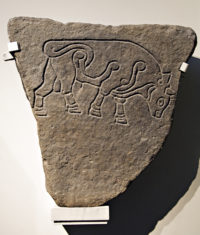

The orgy of destruction was entirely undeterred by the exceptional discovery of as many as 30 symbol stones engraved with realistic line art of bulls. Now known to be rare Pictish stones, most of them were casually reused as construction materials in the quay wall of the new harbour and are considered lost. Today only six of the Burghead Bulls survive, two in the Burghead visitor centre, the rest in the Elgin Museum, the National Museum of Scotland and the British Museum. All that’s left of the Pictish fort above ground are some lengths of the earth and rubble inner ramparts and a snippet of one of the outer ramparts on the southern side. A subterranean ritual well in a rock-cut chamber discovered during utilities work in 1809 is the most intact remnant of the fort.

The orgy of destruction was entirely undeterred by the exceptional discovery of as many as 30 symbol stones engraved with realistic line art of bulls. Now known to be rare Pictish stones, most of them were casually reused as construction materials in the quay wall of the new harbour and are considered lost. Today only six of the Burghead Bulls survive, two in the Burghead visitor centre, the rest in the Elgin Museum, the National Museum of Scotland and the British Museum. All that’s left of the Pictish fort above ground are some lengths of the earth and rubble inner ramparts and a snippet of one of the outer ramparts on the southern side. A subterranean ritual well in a rock-cut chamber discovered during utilities work in 1809 is the most intact remnant of the fort.

Archaeological digs at Burghead began in the late 19th century (less than a hundred years from “who cares?” obliteration to desperately seeking antiquity). They usually focused on the perimeter of the structure — the inner and outer ramparts, the defensive wall — and while the occasional artifact was found, the fort was generally considered to have been gutted beyond recovery by the construction of the town and harbour.

University of Aberdeen archaeologists have been excavating the site since 2015 and this season has seen remarkable discoveries: evidence of a Pictish longhouse and a late 9th century Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great. Pictish architectural remains are rare and there are major lacunae in our understanding of Pictish buildings. The longhouse gives archaeologists a unique opportunity to study the Picts’ living spaces within a great fort. The coin not only helped establish the dates for the occupation of the longhouse, but it is from a key transitional period when Viking raiders began savaging Pictish territories and would ultimately bring about the demise of Pictish kingdoms.

University of Aberdeen archaeologists have been excavating the site since 2015 and this season has seen remarkable discoveries: evidence of a Pictish longhouse and a late 9th century Anglo-Saxon coin of Alfred the Great. Pictish architectural remains are rare and there are major lacunae in our understanding of Pictish buildings. The longhouse gives archaeologists a unique opportunity to study the Picts’ living spaces within a great fort. The coin not only helped establish the dates for the occupation of the longhouse, but it is from a key transitional period when Viking raiders began savaging Pictish territories and would ultimately bring about the demise of Pictish kingdoms.

Dr Gordon Noble, Head of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen, said: “The assumption has always been that there was nothing left at Burghead; that it was all trashed in the 19th century but nobody’s really looked at the interior to see if there’s anything that survives inside the fort.

“But beneath the 19th century debris, we have started to find significant Pictish remains. We appear to have found a Pictish longhouse. This is important because Burghead is likely to have been one of the key royal centres of Northern Pictland and understanding the nature of settlement within the fort is key to understanding how power was materialised within these important fortified sites.

“There is a lovely stone-built hearth in one end of the building and the Anglo-Saxon coin shows the building dates towards the end of the use of the fort based on previous dating. The coin is also interesting as it shows that the fort occupants were able to tap into long-distance trade networks. The coin is also pierced, perhaps for wearing; it shows that the occupants of the fort in this non-monetary economy literally wore their wealth.

“Overall these findings suggest that there is still valuable information that can be recovered from Burghead which would tell us more about this society at a significant time for northern Scotland – just as Norse settlers were consolidating their power in Shetland and Orkney and launching attacks on mainland Scotland.”

That bull looks indeed very ‘pictish‘ :love:

Wonderful to see this excavation taking place. I’ve been to Burghead many times having spent 16 years in Moray from the 70s through the early 90s.

My understanding has been that the ‘who cares’ phase was due to the Crown’s desire to resettle in coastal towns those Highland crofters whom they couldn’t export to the colonies. It was, after all, the tail end of the Clearances. So the Red Coats ‘romanized’ Burghead with the gridded street layout it’s had ever since.

I’d always wondered what the fort might have looked like, so appreciate the 1809 drawing you linked to.

Thank you for another wonderful post!

It is a quite lovely bull.

Can anyone show livirius how to correct his blogs subscription list? I can FOLLOW the list in WordPress, but I CANNOT TURN ON daily blog posts. These options are greyed out, unavailable to me. The only way I get the blog is to visit the blog home page.

I used to receive his daily posts, does anyone know what changed?

Love your usage. Lacuna? Had to look it up. Great stuff!

Sorry. Lacunae. Will learn to type someday…

Here’s something I don’t understand: the term ‘rock cut.”

I always think it should be ‘cut rock’. Otherwise, it sounds like the rock is the device used to ‘cut’ the tomb (or well, etc,)

Thoughts?

When artists cut rock, the rock is cut.

Sometimes, if all goes well, the result -i.e. the ‘cut rock’- will be a rock cut. Grammatically, the verb ‘cut’ will remain -so to speak, rock-solid– ‘cut’ in all its tenses and flexion, which might explain this ‘phenomenon’ (as far as a non-native speaker like me possibly could explain it).

:hattip:

Was this helpful ? Moreover, I could not even imagine how all this would look like in French 😮

Are there more detailed photo data to be found on this site (e.g., shot with a Canon DS-1 with 250mm lens @ f-4.5)? Normally, that stuff is really TL;DR, but these photos had me swapping back and foth, zooming, etc., like crazy to see just where and from what angle they were taken.

The one with the AC/DC researcher had to be with a pretty long lens to get enough depth of field to keep the bench(?) and old stone wall in the background in focus. Damn near felt like a scientist to have worked it all out.

Needless to say, as always all the above was literally done from the comfort of an armchair.

Thank you, Ealdberth, that’s an excellent explanation!