Precious textiles from the reliquary of St King Canute the Holy preserved in the cathedral of Odense, Denmark, have been found to actually belong to his brother’s reliquary. The two were killed together inside a nearby church in 1086 and were laid to rest in shrines. After centuries of having been moved, hidden, hidden again and displayed the reliquary textiles’ origins became nebulous.

Precious textiles from the reliquary of St King Canute the Holy preserved in the cathedral of Odense, Denmark, have been found to actually belong to his brother’s reliquary. The two were killed together inside a nearby church in 1086 and were laid to rest in shrines. After centuries of having been moved, hidden, hidden again and displayed the reliquary textiles’ origins became nebulous.

King Canute IV was the second of the five sons of King Sven Estridsen to rule Denmark after their father’s death in 1076. Canute succeeded to the throne in 1080 but only reigned for six years. He was a proponent of a strong centralized monarchy in tandem with a strong centralized church. He forced feudal nobles and peasants alike to provide him with transportation, supplies and protection as he traveled the country extracting tithes and press-ganged labor for the construction of new churches.

He pushed his luck even further in 1085 when he demanded a huge armada and crew for an invasion of England. The Danes left the rendezvous spot before his arrival, blaming the weather, and the bulk of the would-be invasion fleet went home. Canute was furious and imposed insane punitive fines that would have bankrupted everyone. Nobles and peasants rebelled, destroying royal property and forcing the king to flee to Odense.

Canute, together with his younger half-brother Benedikt and 17 housecarls (paid bodyguards), took refuge in the small wooden church of St. Alban’s in Odense. The rebels attacked the church and killed both Benedikt and Canute, plus all 17 of the housecarls. The monks of St. Alban’s buried the bodies of the king and prince in front of the altar where Canute had been slain as he prayed on his knees.

His death was almost immediately seen as a martyrdom, and indeed he would be canonized 14 years after the killing. The bodies, Canute in an oak shrine with columns, Benedikt in an oak shrine with a hipped lid, were moved to a new, large Romanesque church built in Canute’s honor southwest of St. Alban’s.

His death was almost immediately seen as a martyrdom, and indeed he would be canonized 14 years after the killing. The bodies, Canute in an oak shrine with columns, Benedikt in an oak shrine with a hipped lid, were moved to a new, large Romanesque church built in Canute’s honor southwest of St. Alban’s.

A hagiography of Canute written by Ælnoth of Canterbury, a monk at the new church dedicated to the saint, in the first quarter of the 12th century described Canute’s bones as being wrapped in silk and placed in a bejeweled reliquary. Even when the church was rebuilt in the late 13th century by a Gothic cathedral, the reliquaries of the brothers were still venerated in the crypt.

Come the Reformation, relics of saints fell most distinctly out of favor, and in 1536, the reliquaries were stripped of precious metals and gems and walled up. They were uncovered again in 1582 when the church was again rebuilt. The large oak reliquaries decorated with metal fittings and crystals were described as lined with silks and the bones wrapped in fine linen and covered with more silk textiles.

Come the Reformation, relics of saints fell most distinctly out of favor, and in 1536, the reliquaries were stripped of precious metals and gems and walled up. They were uncovered again in 1582 when the church was again rebuilt. The large oak reliquaries decorated with metal fittings and crystals were described as lined with silks and the bones wrapped in fine linen and covered with more silk textiles.

The reliquaries were sealed up again, this time in a wall behind the altar. They had been placed vertically, so when they were rediscovered again in 1694, all the bones, silks and linen had tumbled to the bottom of the reliquary shrines. Antiquarians examined the contents, intrigued by the historic textiles, and documented silks in one reliquary with a hipped lid and linen in the reliquary with columns. The shrines were then again immured in a vertical position.

They were removed for good from their cramped vertical quarters only in 1833, given new glass lids and put on display in the church. Inside the hipped roof shrine was red and blue silk textile with eagles and a yellow silk pillow cover with a motif of birds and crosses. The columned reliquary contained just a pillow and fringed linen cloth.

The larger, more important silks from the hipped lid reliquary were sent for conservation to what would become the National Museum in Copenhagen. When they were returned in 1875, they were placed in the reliquary with the columns because that was Canute’s shrine and the most expensive textiles seemed like they should go with the saintly king instead of his brother.

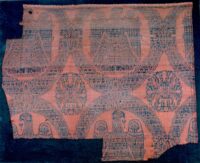

Samples of nine of the textiles taken during conservation in 2008 have been analyzed as part of a new study to determine their age, condition and historical context. The two most splendid of the textiles are a pillow with birds, likely peacocks, alternating with stylized crosses or trees, and a blue and red samite weave with elaborate eagle decoration.

Samples of nine of the textiles taken during conservation in 2008 have been analyzed as part of a new study to determine their age, condition and historical context. The two most splendid of the textiles are a pillow with birds, likely peacocks, alternating with stylized crosses or trees, and a blue and red samite weave with elaborate eagle decoration.

Radiocarbon dating found that the textiles date from the mid-11th century to the mid-12th, in accordance with the date the brothers were enshrined around 1100. Dendrochronoligcal analysis of the wood of the Canute’s shrine with the columns also confirmed the date range, having been harvested approximately 25 years after 1074.

Radiocarbon dating found that the textiles date from the mid-11th century to the mid-12th, in accordance with the date the brothers were enshrined around 1100. Dendrochronoligcal analysis of the wood of the Canute’s shrine with the columns also confirmed the date range, having been harvested approximately 25 years after 1074.

Neither the silk pillow with birds and crosses nor the Eagle Silk could have originated in Denmark or thereabouts.

The Eagle Silk and the pillow with the bird motif. It is the general and most likely assumption that the preserved silks must have been part of the costly gifts that were sent from South Italy to St Canute’s shrine by his widow, Edel. As duchess of Calabria and Apulia Edel had access to high-quality silks from the Byzantine Empire. Perhaps the textiles were brought to Denmark by St Canute’s half-brother, King Erik 1. Ejegod, who visited Italy in order to promote the sanctification of Canute and who is known to have visited Bari in Apulia on this occasion.

The textiles are the largest and best-preserved high-status textiles from the High Middle Ages in Denmark. At the time of Canute’s canonization and enshrinement, silk weaving in Europe was not yet established outside the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire and silk was both a precious and a much-coveted import article.

The argument made in 1875 when the silks from the hipped lid shrine were moved to the column shrine was the best belonged in the king’s shrine, but while these were the best silks found in the reliquaries, they were not the best someone like Erik would have had access to via the Byzantine Empire.

The precondition for the argument that the best silks should belong in the king’s shrine is that all original textiles are preserved. That is clearly not the case. The description of the king’s shrine from 1582 mentions a double yellow silk with yellow silk embroidery as well as a golden piece of textile. These silks seem to have been lost. On the other hand, the description does not mention such characteristic textiles as the Eagle Silk or the pillow with the birds. The most reasonable conclusion is that most of the preserved textiles right from the beginning lay in Benedikt’s shrine where they were also found in 1694–96 and in 1833. The silks are indeed fine and suitable for a saint. But as the somewhat enforced use of the silk for the pillow with the birds indicate, Benedikt’s shrine could not necessarily claim the best silks or the best handicraft. The silks in St Canute’s shrine were probably of even better quality. That might explain why most of the textiles which were found in the shrine in 1582 have disappeared, probably stolen like all the metal fittings on the shrine. The shrine was clearly plundered for all valuables. It is a likely—but unverifiable suggestion—that the shrine with the hipped lid was the shrine which is recorded to have been stripped of its silver and copper fitting in connection with the large confiscations of precious metal in 1536.

King Erik I visited Bari in Apulia?

A couple of years ago, while I was entertaining a bunch of young kittens in the medieval ruins in Paphos, I accidentally saw a plate, remembering that he had died there ‘on his way to the Holy Land’. Apparently, the trip to Bari had indeed be a much earlier one. The corresponding small church in Paphos is still standing, but I cannot tell, if it is the original one and I saw no official grave.

Canute’s half-brother, it seems, had traveled via what today is Russia to Byzantion/ Constantinople, and the plan seems to have been to visit Paphos, and from there the Holy Land. Instead, he was buried in Cyprus, and only Queen Boedil made it to Jerusalem.

To trade silk and linnen to places like Denmark was seemingly no big deal even back then. Very expensive maybe, but certainly not big.

cf.: Chrysopolitissa (Paphos) – Paleochristian basilica