Archaeologists working with a local historian and metal detectorists have discovered an Iron Age weapons deposit that is the largest ever found in the northwestern German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Between 2018 and 2020, volunteers coordinated with archaeologists from the Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe (LWL) to scan the top of the Wilzenberg mountain in the hilly Sauerland region. In three seasons, the survey recovered more than 150 metal weapons, armour and horse fittings from the pre-Roman Iron Age. Most of the objects date to around 300 B.C. through the 1st century B.C., with the coins and blades dating to the later part of the range.

Archaeologists working with a local historian and metal detectorists have discovered an Iron Age weapons deposit that is the largest ever found in the northwestern German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Between 2018 and 2020, volunteers coordinated with archaeologists from the Regional Association of Westphalia-Lippe (LWL) to scan the top of the Wilzenberg mountain in the hilly Sauerland region. In three seasons, the survey recovered more than 150 metal weapons, armour and horse fittings from the pre-Roman Iron Age. Most of the objects date to around 300 B.C. through the 1st century B.C., with the coins and blades dating to the later part of the range.

The Wilzenberg, a mountain 658 meters (2159 feet) high, stands out on a ridge of smaller forested hills in what is now the Sauerland-Rothaargebirge nature park. Known as the Holy Mountain of the Sauerland, the geographic singularity has been held in reverence at least since the 3rd century B.C. At the summit is the Wallburg, the remains of a hill fort built in the 3rd-2nd century B.C. from wood, stone and earth. Christian worshipers added a second circular structure in the 9th or 10th century. A chapel was documented at the site in 1543 when it was already a site of pilgrimage. The last hermit to renounce the world and choose an ascetic life atop the Wilzenberg only died around 1850, and pilgrims still flock to the mountain for processions on Ascension Day (39 days after Easter) and Trinity Day (first Sunday after Pentecost, May 30th this year).

The Wilzenberg, a mountain 658 meters (2159 feet) high, stands out on a ridge of smaller forested hills in what is now the Sauerland-Rothaargebirge nature park. Known as the Holy Mountain of the Sauerland, the geographic singularity has been held in reverence at least since the 3rd century B.C. At the summit is the Wallburg, the remains of a hill fort built in the 3rd-2nd century B.C. from wood, stone and earth. Christian worshipers added a second circular structure in the 9th or 10th century. A chapel was documented at the site in 1543 when it was already a site of pilgrimage. The last hermit to renounce the world and choose an ascetic life atop the Wilzenberg only died around 1850, and pilgrims still flock to the mountain for processions on Ascension Day (39 days after Easter) and Trinity Day (first Sunday after Pentecost, May 30th this year).

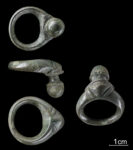

In 1950, a small cache of three spear tips was discovered wrapped by two swords that had been deliberately coiled around the points. Among the recent discoveries are around 40 spear tips. There are also fragments of shield bosses, belt hooks, tools, a fibula, three silver coins and an extremely rare horse bridle that has handles at the bit. These were likely used for horses that were pulling chariots; the handles allowed for precision steering necessary in the heat of battle.

In 1950, a small cache of three spear tips was discovered wrapped by two swords that had been deliberately coiled around the points. Among the recent discoveries are around 40 spear tips. There are also fragments of shield bosses, belt hooks, tools, a fibula, three silver coins and an extremely rare horse bridle that has handles at the bit. These were likely used for horses that were pulling chariots; the handles allowed for precision steering necessary in the heat of battle.

But there was no battle on the Wilzenberg, or at least no archaeological evidence of a violent clash has ever been recorded. The damage to the  weapons and armature was not inflicted in a war. The tips of spears and lances were blunted, the iron bosses broken off the shields and left in place. A few pieces were buried, but most of them simply subsided into the ground. It’s not clear whether they were scattered on the mountaintop in a single event or over time.

weapons and armature was not inflicted in a war. The tips of spears and lances were blunted, the iron bosses broken off the shields and left in place. A few pieces were buried, but most of them simply subsided into the ground. It’s not clear whether they were scattered on the mountaintop in a single event or over time.

“According to current research, it is conceivable that a fight took place in the area around Wilzenberg and that the winners completed their triumph by bringing the captured weapons, belts and harnesses to the Wallburg”, explains LWL archaeologist Dr. Manuel Zeiler. The winners apparently willfully damaged many of the pieces before they were then put on display on the Wilzenberg and left to their own devices. These assumptions are based on the results of French research, which shows that such cult acts in Iron Age Europe took place primarily in the Celtic culture and on its periphery. Weapons of inferior opponents were ritually destroyed; these actions were usually preceded by a battle. […]

Especially in the last centuries BC In the area between France in the west and Slovakia in the east, such weapons depots were set up again and again. Now the hoard find from Wilzenberg in the Sauerland can possibly close research gaps.

Usually, the activities on those kind of hill forts happened in ‘periods’, i.e. sometimes beginning already in the Neolithic or Bronze Age, people moved up there whenever necessary, with phases of hardly any activity at all.

The structure from the 9th or 10th century reminds of what, according to Widukind of Corvey in his three-volume ‘Res Gestae Saxonicae’, Emperor Henry I as king of East Francia ordered in 926AD due to imminent Magyar invasions:

———

“…ex agrariis militibus nonum quemque eligens in urbibus habitare fecit, ut ceteris confamiliaribus suis octo habitacula extrueret, frugum omnium tertiam partem exciperet servaretque. Caeteri vero octo seminarent et meterent frugesque colligerent nono et suis eas locis reconderent. ….”

…Every 9th of the king’s rural warriors shall live in a ring wall and shall arrange housing for his remaining 8 buddies. He shall keep a third of all the harvest and those 8 buddies shall supply him. Also, councils, convents and trade shall only take place within those erected ring walls….

———

To give an example, a description of the ‘Ehrenbürg’ site (a.k.a. “Walberla”), a double-peaked hill in Eastern Franconia in what is now Bavaria, reads as follows (their 9th or 10th century ringwalls, however, were built on hills nearby):

upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bb/Nürnberger_Feldschlange.JPG (A. Dürer)

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ehrenbürg

———

“The hill was a settlement site from the early Neolithic (4000 BCE) until the end of the Roman period in the 5th century CE. In the late 14th century BCE, it became a hill fort; in the early Iron Age (appr. 550–380 BCE), under the Celtic Hallstatt and early La Tène cultures, it was a strongly fortified regional centre, with two gates and a citadel, and finds originating from Mediterranean cultures indicate far-flung trade. Remnants of these fortifications are still discernible. However, in the late Iron Age, during the late La Tène period (appr. 150–30 BCE) the hill was only lightly settled; instead, a large unfortified town grew up nearby […]. After an interruption, there was then possible occupation by Germanic people during the late Roman period, around 400 CE; unlike the Celtic settlement, only on the Rodenstein. Archaeological finds indicate that during the Hallstatt and La Tène periods, the hill was the site of human sacrifices [the hill has two peaks]. Some human bones, such as a woman’s skeleton which was unnaturally bent and buried under boulders, appear to be sacrifices for the luck of a building; some skulls have been cut up and had holes bored in them for use as amulettes; the armless and legless skeleton of a baby, and discarded fragments of human bones with cut marks, both suggest cannibalism. Nine skeletons of newborn babies were also found to have been buried against the eastern foundation of the chapel in the 17th or the 18th century. […] An early 16th-century wooden statue of St. Walburga by Hans Nußbaum used to stand in the chapel, flanked by statues of her brothers.”

——–

:hattip: