Researchers have discovered that a mummy in the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw that is the only known pregnant Egyptian mummy has large cavities in her face not typical of the mummification process that strongly indicate she suffered from nasopharyngeal cancer.

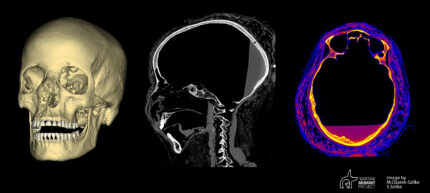

“When preparing the skull of the mummy we examined for 3D prints, we noticed large defects in parts of the facial bones, larger than those usually formed during mummification runs” – Marzena Ożarek-Szilke, anthropologist and archaeologist from the Medical University of Warsaw (MUU) told PAP . As she added, such smaller cavities usually arose when the brain was removed through one of the nostrils. At that time, i.a. the ethmoid bone was broken while “picking” out the brain.

Prof. Rafał Stec from the Oncology Clinic of the Medical University of Warsaw. PAP asked the scientist what proves that the Egyptian woman suffered from cancer and whether it is possible to conclude with high probability that this was the case without sampling.

“First, there are atypical changes in the nasopharyngeal bones that are not typical of the mummification process, according to experts in the study of mummies. Secondly, the opinions of radiologists based on computed tomography indicate the possibility of changes in the bones due to neoplastic causes “- the scientist pointed out. He added that the young age of the deceased and the lack of any other cause of death may very likely indicate “an oncological cause”.

The 1st century B.C. mummy inside its decorated sarcophagus was brought to Poland in December 1826 and given to the University of Warsaw to expand its nascent antiquities collection. This was the era of mummy unwrapping parties, but in a stroke of good fortune, the Warsaw mummy managed to survive the period fully wrapped and unmolested. Documentation from the 19th century claimed it was the mummy of a lady, but after World War I, researchers translated the hieroglyphics on the coffin and the inscription identified the sarcophagus’ owner as a priest named Hor-Jehuti.

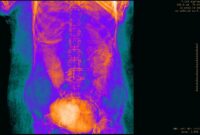

That mistake was only corrected when new X-rays and CT scans taken in 2016 found that the mummy was actually an adult woman. Two years after that, a researcher examining the scans spotted an object in the pelvis region. At first she thought it might be mummification materials used to fill the abdomen, but a closer analysis of the imaging results revealed the mass had a small head, hands and a foot. It seems the natron packed into the body had all but sealed off the uterus and mineralized the fetus, preserving much of its tissue and making it visible in X-ray and CT images even though the bones largely decomposed. Scans also revealed that she was young, between 20 and 30 years old when she died, and that she had been in her early third trimester of pregnancy (26th-30th week).

That mistake was only corrected when new X-rays and CT scans taken in 2016 found that the mummy was actually an adult woman. Two years after that, a researcher examining the scans spotted an object in the pelvis region. At first she thought it might be mummification materials used to fill the abdomen, but a closer analysis of the imaging results revealed the mass had a small head, hands and a foot. It seems the natron packed into the body had all but sealed off the uterus and mineralized the fetus, preserving much of its tissue and making it visible in X-ray and CT images even though the bones largely decomposed. Scans also revealed that she was young, between 20 and 30 years old when she died, and that she had been in her early third trimester of pregnancy (26th-30th week).

Another two years of research ensued to confirm that there were no other pregnant Egyptian mummies known and the discovery was announced to the public in April 2021. Maternal and infant mortality rates were high in antiquity, so it’s surprising that there is so little evidence of it on the archaeological record in a society were mummification was so widespread. Skeletal remains of pregnant women and mummified fetuses have been found before (there were two fetuses in Tutankhamen’s tomb), but they are extremely rare.

Another two years of research ensued to confirm that there were no other pregnant Egyptian mummies known and the discovery was announced to the public in April 2021. Maternal and infant mortality rates were high in antiquity, so it’s surprising that there is so little evidence of it on the archaeological record in a society were mummification was so widespread. Skeletal remains of pregnant women and mummified fetuses have been found before (there were two fetuses in Tutankhamen’s tomb), but they are extremely rare.

The multi-disciplinary Warsaw Mummy Project team is still studying the mummy. They suspect she suffered from a malignant tumor, but that can only be confirmed by histopathological examination. They plan to extract tissue samples from the cavities to compare them to cancer samples found in other Egyptian mummies currently stored in US and UK tissue banks.

According to the researchers, the analysis of mummies may contribute to the development of modern medicine. As explained by prof. Stec, it will be possible to learn about the “molecular signature” of cancers and compare it with current cancers. He expressed hope that it will also broaden the knowledge about the evolution of cancer and that it may indicate further research directions in both diagnostics and treatment.

It would seem that if you are going to make a claim that a person died of nasopharyngeal carcinoma there would be far more evidence for this on the CT scan. As far as “lack of any other cause of death”, gee, could it just be that the baby died in utero leading to the mother’s death?

Herodotus reports a few centuries earlier about Egyptian physicians and also about embalmers. As there is more than one embalming method –probably even more than three– there might be more than one way to cut out a tumor or e.g. to get a dead brain out of a skull. Also there certainly were different levels of mastery in doing so. There might have been even different “crooked iron tools”.

:hattip:

————–

2.84. The art of medicine among them is distributed thus:–each physician is a physician of one disease and of no more; and the whole country is full of physicians, for some profess themselves to be physicians of the eyes, others of the head, others of the teeth, others of the affections of the stomach, and others of the more obscure ailments.

2.86. …the third [embalming method] is the least expensive of all. … after they have agreed for a certain price depart out of the way, and the others being left behind in the buildings embalm according to the best of these ways thus:– First with a crooked iron tool they draw out the brain through the nostrils, extracting it partly thus and partly by pouring in drugs; and after this with a sharp stone of Ethiopia they make a cut along the side and take out the whole contents of the belly, and when they have cleared out the cavity and cleansed it with palm-wine they cleanse it again with spices pounded up: then they fill the belly with pure myrrh pounded up and with cassia and other spices except frankincense, and sew it together again. Having so done they keep it for embalming covered up in natron for seventy days, but for a longer time than this it is not permitted to embalm it; and when the seventy days are past, they wash the corpse and roll its whole body up in fine linen cut into bands, smearing these beneath with gum, which the Egyptians use generally instead of glue…

————–