Sharp wooden stakes used as defensive barriers of a Roman fort have been discovered in Bad Ems, western Germany. Preserved in the water-logged soil of Blöskopf hill, the spikes were mounted in a v shape onto a central post. Enemies falling into the defensive ditch would meet the business ends of this very sharp structure. There are references to these kinds of rigs in ancient sources, but this is the first example ever discovered.

Sharp wooden stakes used as defensive barriers of a Roman fort have been discovered in Bad Ems, western Germany. Preserved in the water-logged soil of Blöskopf hill, the spikes were mounted in a v shape onto a central post. Enemies falling into the defensive ditch would meet the business ends of this very sharp structure. There are references to these kinds of rigs in ancient sources, but this is the first example ever discovered.

Roman troops had been in the area since 55 B.C., when Julius Caesar built a bridge over the Rhine between what are now Koblenz (10 miles west of Bad Ems) and Andernach. Germanicus built a castellum (guard tower) in Koblenz in 9 B.C. Later in the first century a castrum (miliary fort) was built in Bad Ems.

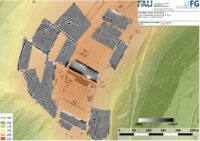

Recent excavations were triggered by a rather brilliant hunter’s report of differences in grain color that could indicated underground structures. Drone photography and geomagnetic scans confirmed that under the grain were large double ditches that formed defensive perimeter of a Roman camp. It would have been a huge Roman camp: eight hectares with 40 wooden towers — much larger than the known to have been built one at Bad Ems. It was meant to be permanent but it was never completed. Only a warehouse was built in the end and a few years later the camp was burned down.

Recent excavations were triggered by a rather brilliant hunter’s report of differences in grain color that could indicated underground structures. Drone photography and geomagnetic scans confirmed that under the grain were large double ditches that formed defensive perimeter of a Roman camp. It would have been a huge Roman camp: eight hectares with 40 wooden towers — much larger than the known to have been built one at Bad Ems. It was meant to be permanent but it was never completed. Only a warehouse was built in the end and a few years later the camp was burned down.

A second, much smaller camp, was unearthed a mile away. The stake structure was part of the defenses of this second camp.

Exploratory excavations carried out [in the Blöskopf area] in 1897 uncovered processed silver ore, raising the assumption that a Roman smelting works was once located there. The thesis was further supported by the discovery of wall foundations, fire remains and metal slag. For a long time it was assumed that the smelting works were connected to the Limes, built some 800 meters to the east at around 110 AD. These assumptions, considered valid for decades, have now been disproved: The supposed furnace in fact turned out to be a watchtower of a small military camp holding about 40 men. It was probably deliberately set on fire before the garrison left the camp. The spectacular wooden defense structure was discovered on literally the penultimate day of the excavations – along with a coin minted in 43 AD, proof that the structure could not have been built in connection with the Limes.

We know from Tacitus’ Annals that in 47 A.D., Emperor Claudius dispatched an arriviste praetor by the name of Curtius Rufus (who may or may not have been the son of a gladiator) to the area in order to mine silver.

[Curtius Rufus] had opened mines in the territory of the Mattiaci for working certain veins of silver. The produce was small and soon exhausted. The toil meanwhile of the legions was only to a loss, while they dug channels for water and constructed below the surface works which are difficult enough in the open air.

The excavation did indeed discover a shaft and tunnel system that appears to be of Roman origin, but it never reached the silver vein. They gave up too early because the silver was just a few feet beneath the tunnels.

The excavation did indeed discover a shaft and tunnel system that appears to be of Roman origin, but it never reached the silver vein. They gave up too early because the silver was just a few feet beneath the tunnels.

The search for silver would explain the presence of two camps. The legions provided necessary (hard) labor to dig for silver, and the necessary security to protect the precious metal from Germanic raids.

…and the VERY FIRST picture that I click says “FAU” – From back home in Erlangen, Institute of Prehistory and Early History at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, in Franconia, i.e. north of the ‘Limes’.

However, Bad Ems is indeed where the (later) ‘Upper Germanic Limes’ begins in the West. Back in December, I saw –at the other end– in “Castra Regina” the Roman stone structures, not the ones near the river bank, but on the opposite corner of the former Roman camp, rather close to where today the main station is: Yes, the dude in red is me.

Close nearby, only 5km to the east, at the ‘Villa Rustica’ in Burgweinting, at the premises of BMW, the severed and scalped(!) heads of what in the 3rd century must have been the inhabitants, were found dumped into a well. Unfortunately, I could not inspect the skull(s) myself, as we visited the *wrong* museum.