A coin recently acquired by Centre Charlemagne in Aachen bears the name of Charlemagne and his third wife Fastrada. It is not only the first known example of her name on a coin, it is the first known example of any queen (or woman, for that matter, other than the Virgin Mary) named on a Carolingian coin.

Fastrada was born around 765, the daughter of powerful East Frankish Count Rudolph. Charlemagne married her in 783, only five months after the death of his second wife Himiltrude, to cement an alliance with her father in his war against the Saxons. They would go on to have two daughters over 11 years of marriage before Fastrada’s death in 794. No portraits of her have survived.

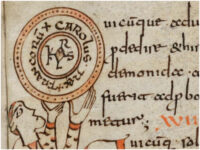

Minted between 793 and 794, likely in Aachen, the coin is inscribed on the obverse side with +CARoLVSREXFR[ancorum], (‘Charles, king of the Franks’), and on the reverse +FASTRADA REGIN[a], (‘Queen Fastrada’), around the royal monogram of Charlemagne (KAROLVS). It is a silver denier of a type known as the monogram denier after the KAROLVS monogram.

Minted between 793 and 794, likely in Aachen, the coin is inscribed on the obverse side with +CARoLVSREXFR[ancorum], (‘Charles, king of the Franks’), and on the reverse +FASTRADA REGIN[a], (‘Queen Fastrada’), around the royal monogram of Charlemagne (KAROLVS). It is a silver denier of a type known as the monogram denier after the KAROLVS monogram.

Carolingian queens were not written about very much by chroniclers, and what was written about Fastrada was less than flattering. Writers blamed her cruelty (no specifics as to its nature) for the rebellion of Charlemagne’s son Pippin the Hunchback in 792. In the Royal Frankish Annals of 792, however, Charlemagne’s reunion with Fastrada in Worms after his long absence fighting the Avars, is described as warm and happy. A letter from Charlemagne to her survives in which he addresses her as “our dear and very lovely wife the queen.”

These are unusually glowing terms for a Frankish royal marriage, and may explain why Charlemagne took the extraordinary step of putting their names together on a coin. The presence of Fastrada’s name is all the more notable because Charlemagne had made a point of eliminating all personal names but his from the coinage after his accession to the throne. It suggests a willingness to share power with his third wife in a very public, visible way.

Charlemagne must have been inspired by King Offa of Mercia who in 792 had had a penny minted bearing the name of his wife Queen Cynethryth. The two had extensive trade contacts and at one point were actively planning a marriage between Charles’ son and Offa’s daughter. It can’t be a coincidence that the silver denier duplicates the Cynethryth penny’s syntax with the Latinate title of ‘REGIN(a)’ for Fastrada.

Despite the parallels between these Mercian and Carolingian coinages, three significant differences are also evident from the discussion above. The first is the scale: as was noted earlier, there are more than fifty recorded examples of Cynethryth’s coinage, from numerous different dies, but this is the first and to date only specimen of a coin of Fastrada. The second is the design: Cynethryth’s was in the main a portrait type, Fastrada’s a regular monogram issue. The third is the timing of their appearance: the minting of Cynethryth’s coinage stopped at almost exactly the same time as Fastrada’s began. What, if any, is the significance of these dissimilarities?

With regard to the scale, this might well reflect nothing more than the duration of minting. Pennies in the name of Cynethryth are believed to have been minted from the introduction of Offa’s Light coinage in the mid-780s until his reform of 792/3. As we have seen, Fastrada died only a matter of months after the introduction of Charlemagne’s new heavier denier, and it is quite possible that minting ceased at that point. As a result, only a small number of coins would have been minted, of which this one specimen has survived. The reason it bore no portrait, unlike the majority of the coins of Cynethryth, is that Charlemagne did not introduce a portrait type until 813, whereas Offa was minting pennies bearing a bust of himself at the very time these coins of his queen were struck, in the 780s. It has indeed been observed that on some of the coins of Cynethryth the portrait is virtually identical to that of Offa himself, though others are more distinctively feminine. In other words, both issues followed the design of their husband’s coinage at the time.