Electoral graffiti are one of the most common types found on the streets and walls of Pompeii. There are more than 1500 documented examples of political campaign electioneering and slogans painted on the walls of Pompeii. Politicians running for office would hire professional graffiti writers to publicize their names, virtues, campaign promises and endorsements by well-known individuals and professional associations (bakers, goldsmiths, mystery cult members, etc.). They even did negative campaigning via graffiti, claiming an opponent was supported by the drunkards and thieves association, for example.

The political graffiti of Pompeii are so extensive that historians have been able to trace which candidates ran for which office in which elections, who endorsed them, who opposed them, what their platforms were; the real meat-and-potatoes of local electoral politics in a 1st century Roman city.

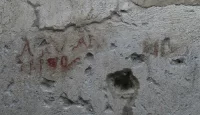

Now a new discovery has added a fresh dimension to our understanding of how campaigns for political office operated. A series of electoral inscriptions have been discovered inside House X in Pompeii’s Regio IX neighborhood, the same villa where the fresco with the fruit focaccia was found earlier this year. The inscriptions were in the room where the lararium, the home’s altar, was located. This was a fully interior space, not the exterior of the house where passersby would see which candidate the homeowner supported. The presence of the inscriptions indicates campaign promotions took place inside private homes.

Now a new discovery has added a fresh dimension to our understanding of how campaigns for political office operated. A series of electoral inscriptions have been discovered inside House X in Pompeii’s Regio IX neighborhood, the same villa where the fresco with the fruit focaccia was found earlier this year. The inscriptions were in the room where the lararium, the home’s altar, was located. This was a fully interior space, not the exterior of the house where passersby would see which candidate the homeowner supported. The presence of the inscriptions indicates campaign promotions took place inside private homes.

The inscriptions are faded and fragmentary, but the remains are legible and promote the campaign of Aulus Rustius Verus, candidate for aedile, the magistrate responsible for public games, markets and the maintenance of sacred and private buildings. Epigraphers translate the longest and clearest two inscriptions as: “I exhort you sincerely to vote for Aulus Rustius Verus, aedile candidate, man worthy of the office.” Verus’ name has appeared before in electoral inscriptions. He owned a grand villa on the Via dell’Abbonzanza and in 73 A.D., a scant six years before the city’s obliteration, he attained the position of duovir, the next step up for aedile and the highest office possible in the city, alongside Gaius Julius Polybius. The graffiti must therefore pre-date 73 A.D.

The inscriptions are faded and fragmentary, but the remains are legible and promote the campaign of Aulus Rustius Verus, candidate for aedile, the magistrate responsible for public games, markets and the maintenance of sacred and private buildings. Epigraphers translate the longest and clearest two inscriptions as: “I exhort you sincerely to vote for Aulus Rustius Verus, aedile candidate, man worthy of the office.” Verus’ name has appeared before in electoral inscriptions. He owned a grand villa on the Via dell’Abbonzanza and in 73 A.D., a scant six years before the city’s obliteration, he attained the position of duovir, the next step up for aedile and the highest office possible in the city, alongside Gaius Julius Polybius. The graffiti must therefore pre-date 73 A.D.

House X’s owner was clearly a supporter and may have been a relative, friend or freedman of Aulus Rustius Verus’. The house had a professional oven so it was a bakery shop as well as a private home, and bakers were more typically freedmen. Bread was a big political issue in Rome. Roman citizens were given free wheat starting in the 2nd century B.C. and the grain dole was thoroughly entrenched under the emperors. The phrase “panem et circensis” (bread and circuses) was coined by the poet Juvenal around 100 A.D. to decry the decline of civic duty, replaced by the public’s craving for cheap/free bread and entertaining distractions. Verus’ initials appear on a millstone in the atrium that was undergoing renovations when Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D. It’s likely that Aulus Rustius was helping to fund the bakery’s renovation, a tidy way to associate his generosity with bread production. This would make the baker his client and therefore bound to support his political endeavors even to the point of putting up billboards in his house.

House X’s owner was clearly a supporter and may have been a relative, friend or freedman of Aulus Rustius Verus’. The house had a professional oven so it was a bakery shop as well as a private home, and bakers were more typically freedmen. Bread was a big political issue in Rome. Roman citizens were given free wheat starting in the 2nd century B.C. and the grain dole was thoroughly entrenched under the emperors. The phrase “panem et circensis” (bread and circuses) was coined by the poet Juvenal around 100 A.D. to decry the decline of civic duty, replaced by the public’s craving for cheap/free bread and entertaining distractions. Verus’ initials appear on a millstone in the atrium that was undergoing renovations when Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D. It’s likely that Aulus Rustius was helping to fund the bakery’s renovation, a tidy way to associate his generosity with bread production. This would make the baker his client and therefore bound to support his political endeavors even to the point of putting up billboards in his house.

The lararium also preserved another surprise for archaeologists: the remains of the last offering made on its altar. Analysis determined the sacrifice was dates and figs burned on the altar with olive pits and pine cones as the fuel. (Note: I have burned dried olive pits in a fireplace and they smell just as fantastic as you think they would.) The burned offerings were topped with a whole egg and then the altar covered with a tile.

The lararium also preserved another surprise for archaeologists: the remains of the last offering made on its altar. Analysis determined the sacrifice was dates and figs burned on the altar with olive pits and pine cones as the fuel. (Note: I have burned dried olive pits in a fireplace and they smell just as fantastic as you think they would.) The burned offerings were topped with a whole egg and then the altar covered with a tile.

when was the discovery?