A group of Iron Age bronze, copper and lead objects found near a spring in Anglesey, Wales, was declared treasure at a coroner’s inquest on Wednesday. The 16 artifacts were discovered by metal detectorist Ian Porter in two adjacent areas at two different times — some of them in March and the rest in December of 2020. They include Iron Age chariot fittings from the late 1st century A.D., Roman cavalry fittings from the same period and other metal objects from the Romano-British period.

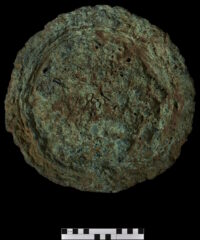

The Roman objects are parts of three bridle bits, a terret, four phalerae (decorative discs from harnesses) and a socketed terminal shaped like a rather jovial ram’s head. There is also a large copper ingot weighing 45 pounds that was likely extracted by the Romans from the copper mine at Parys Mountain which had been mined for centuries before the Roman conquest in the 1st century. Other Roman objects in the group are a copper alloy fibula, a lead pot repair and four copper coins dating from 156-157 A.D., 260-268 A.D., 330-331 A.D. and 364-378 A.D.

The artefacts were all discovered near and around where a spring emerges in a boggy area of a modern field, liable to waterlogging. These unusual bronze, copper and lead artefacts are thought to have been gifted as repeated religious offerings around an ancient sacred spring source during the Late Iron Age and into the Romano-British period. The chariot fittings, cavalry harness pieces and brooch were all placed around AD 50-120, around the time of, or soon after the invasion of the island by the Roman army in AD 60/61. The coins and other artefacts suggest a continuing practice of votive gifting around the spring throughout the Roman period, the latest coin in the group being struck around AD 364-378. […]

Adam Gwilt, Principal Curator for Prehistory at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales said:

“This culturally mixed artefact group, containing both Iron Age chariot fittings and Roman cavalry fittings, is an important new find for the island. It was placed during or in the aftermath of the period of invasion of the island by the Roman army. This dramatic event is vividly captured by the Roman author Tacitus, writing about the strange first encounter between Roman soldiers and Druids on Anglesey. This group of gifted objects illustrates how watery locations, including the sacred lake site at Llyn Cerrig Bach, were seen as significant places for religious ceremony at this time of conflict and change.

We have only Tacitus as an ancient source on the Roman invasion of Anglesey which happened in two attacks more than 15 years apart. The first invasion was led by the Provincial governor of Britannia, Suetonius Paulinus, in 60-61 A.D. He was victorious on the battlefield but was compelled to retreat to handle the Boudican uprising back in England. The second invasion under Gnaeus Julius Agricola in 77 A.D. was successful and Anglesey remained under Roman control until they withdrew from Britain in the early 5th century.

We have only Tacitus as an ancient source on the Roman invasion of Anglesey which happened in two attacks more than 15 years apart. The first invasion was led by the Provincial governor of Britannia, Suetonius Paulinus, in 60-61 A.D. He was victorious on the battlefield but was compelled to retreat to handle the Boudican uprising back in England. The second invasion under Gnaeus Julius Agricola in 77 A.D. was successful and Anglesey remained under Roman control until they withdrew from Britain in the early 5th century.

Here’s how Tacitus describes Suetonius Paulinus first encounter with the people of Anglesey (he calls the island Mona; it is called Môn in Welsh) in The Annals XIV, 29-30:

Now, however, Britain was in the hands of Suetonius Paulinus, who in military knowledge and in popular favour, which allows no one to be without a rival, vied with Corbulo, and aspired to equal the glory of the recovery of Armenia by the subjugation of Rome’s enemies. He therefore prepared to attack the island of Mona which had a powerful population and was a refuge for fugitives. He built flat-bottomed vessels to cope with the shallows, and uncertain depths of the sea. Thus the infantry crossed, while the cavalry followed by fording, or, where the water was deep, swam by the side of their horses.

On the shore stood the opposing army with its dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair dishevelled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds. Then urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the foe in the flames of his own brands. A force was next set over the conquered, and their groves, devoted to inhuman superstitions, were destroyed. They deemed it indeed a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their deities through human entrails.

Oriel Môn, a museum in Llangefni less than 10 miles from the find site, is hoping to acquire the group for its permanent collection after the valuation process.

As it seems, those “sacred groves” were here not entirely “destroyed” –as indicated by Tacitus, who happened to be Agricola’s son-in-law. They are referred to in English as “Nemeton” (pl.: nemeta).

In Latin, we have ‘nemus’ (pl.: nemora), a “tract of woodland, forest pasture, meadow with shade, grove”, and ‘lucus’ (pl.: luci), a “sacred grove, consecrated wood, park surrounding a temple”.

In Old Irish there is ‘nemed’, a sanctuary, cf. place names like e.g. Nemetacum (Arras), Nemetodurum (Nanterre), Drynemeton (i.e. the Galatian Δρυνεμετον in what today is Turkey) or the Nemetes people.

Latin inscriptions from the area inhabited by the Nemetes invoke the gods ‘Mars Loucetius’ and ‘Nemetona’, there is e.g. the Eisenberg inscription (Pfalz region):

——-

[In h(onorem) d(omus)] d(ivinae) Marti Lou/[cetio et] Victoriae Neme/[tonae] M(arcus) A(urelius) Senillus Seve/[rus b(ene)f(iciarius) l]egati urnam cum / [sortib]us et phiala(m) ex / [vo]to posuit l(ibens) l(aetus) m(erito) / [Grat]o et Seleuco co(n)s(ulibus) / X Kal(endas) Maias

“to the divine house, to Mars Loucetius and victoria Nemetona, Marcus Aurelius Senillus Severus, beneficial heir, set up an urn with lots and dish, in free, cheerful, and deserved fulfilment of his vow on the tenth day before the Kalends of May, consulship of Gratus and Seleucus (22 April 221AD).”

——-

In Bk.1 of Tacitus’ Annals an expedition in 15AD is described, who reburied the remains of the three legions, six years after they were massacred in the Battle led by Varus:

—–

“…in the center of the field were the whitening bones of men, as they had fled, or stood their ground, strewn everywhere or piled in heaps. Near lay fragments of weapons and limbs of horses, and also human heads, prominently nailed to trunks of trees. In the adjacent groves were the barbarous altars, on which they had immolated tribunes and first-rank centurions. …”

—–

In 16 AD, after the Romans massacred the Marsi and destroyed their “temple”, a certain Mallovendus revealed to Germanicus the hiding place of one of the three eagles that had been lost in Varus’ battle.

It may be hard to tell if it were Romans or Britons, who put those metal objects into that spring 🤔️

There are real ‘phalerae’, while there are only depicted ones on the cenotaph of one of Varus’ butchered centurions, Marcus Caelius, whose “bones” were never identified.

I just want to thank you. I know putting together this website is time consuming and I appreciate the articles!