The full-sized reconstruction of the colossal statue of Constantine that once stood in the Basilica of Maxentius in the Roman Forum has gone on display in the garden of the Villa Caffarelli Garden, just behind the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill where the surviving fragments of the original statue are exhibited in the entrance courtyard.

The full-sized reconstruction of the colossal statue of Constantine that once stood in the Basilica of Maxentius in the Roman Forum has gone on display in the garden of the Villa Caffarelli Garden, just behind the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill where the surviving fragments of the original statue are exhibited in the entrance courtyard.

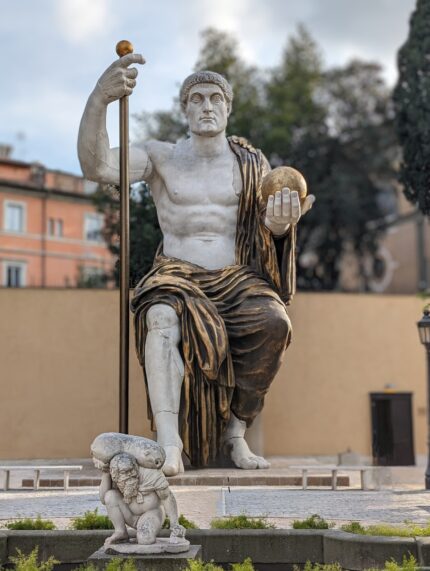

The original colossus was an acrolith (a composite where the head, chest and limbs are made of expensive materials while the hidden structural elements were wood covered with draped clothing) of Constantine seated and enthroned in the style of the cult statue of Jupiter in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline. It may have even been reworked from a statue of Jupiter, as there is evidence the head was recarved from a figure with a high forehead and a beard into the clean-shaven, wavy-banged Constantine. Created between 312 and 315 A.D., the colossus was placed in the western apse of the Basilica Nova, also known as the Basilica of Maxentius. After the Fall of Rome, the statue was looted for the gilded bronze draped around the body and broken up. Nine pieces of it, including the head, hand, foot and knee, were unearthed in 1486 and relocated to the Palazzo dei Conservatori by Michelangelo when he was working on the Capitoline piazza in 1536–1546. A tenth fragment was found in 1951.

The reconstruction was a joint collaboration between the Capitoline Superintendency, the Fondazione Prada and Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Preservation. In 2022, the Factum Foundation scanned the 10 surviving fragments of the statue in ultra-high resolution and used the data to create a 3D model, extrapolating the lost parts from the shape and size of the fragments and from surviving examples of smaller-scale statues of seated and enthroned deities/emperors.

The reconstruction was a joint collaboration between the Capitoline Superintendency, the Fondazione Prada and Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Preservation. In 2022, the Factum Foundation scanned the 10 surviving fragments of the statue in ultra-high resolution and used the data to create a 3D model, extrapolating the lost parts from the shape and size of the fragments and from surviving examples of smaller-scale statues of seated and enthroned deities/emperors.

Once the model was mapped out, the material reconstruction was carried out using resin, polyurethane, marble powder, plaster and gold leaf on an aluminum support to make a light-weight but visually accurate replica of the massive original statue. The finished reconstruction is more than 40 feet high.

The new colossus made its debut at the Fondazione Prada in Milan last year. On Tuesday, February 6th, the Colossus of Constantine was unveiled in Rome. Visitors will be able to see the surviving fragments at the Capitoline Museums then pop over to the beautiful garden of the Villa Caffarelli to see what they looked like before they were fragments.