A rare Archaic period (800 – 480 B.C.) Greek bronze statuette of a horse and rider is the star of a new exhibition that opened yesterday at the Getty Villa Museum. This is the first time the statuette has been on public view since it was discovered in Albania five years ago. It dates to around 500 B.C. and is unique for the high quality of its craftsmanship, its intact condition and for having a known findspot excavated by archaeologists.

A rare Archaic period (800 – 480 B.C.) Greek bronze statuette of a horse and rider is the star of a new exhibition that opened yesterday at the Getty Villa Museum. This is the first time the statuette has been on public view since it was discovered in Albania five years ago. It dates to around 500 B.C. and is unique for the high quality of its craftsmanship, its intact condition and for having a known findspot excavated by archaeologists.

“Although bordering on Greece and sharing the Adriatic coast with Italy, Albania is a country whose ancient heritage is less familiar to American museum audiences,” says Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of the Getty Museum. “Focusing on a single, precious object allows us to offer visitors a glimpse into the close artistic connections within the Mediterranean world, and to highlight the complex process of restoration by the Museum’s antiquities conservators, who carried out the analysis and treatment of this delicate archaeological find in collaboration with colleagues at the Albanian Institute of Archaeology in Tirana.”

The statuette was discovered in 2018 during an excavation of an outpost of the ancient Corinthian colony of Apollonia near the modern-day village of Babunjë, only it wasn’t found in the planned dig. Archaeologists from the international team were watching a local farmer plow his onion field when they spotted something in the churned soil. They stopped the plow, preventing the object from meeting a twisted end, and called in their colleagues to explore its archaeological context.

Even still caked with soil, the exceptional detail of the bronze horseman was evident. It is the only luxury object discovered at this site. Previous finds of ceramics and architectural remains point to a modest settlement founded by Greeks as a defensive outpost of Apollonia. Apollonia was something of an insular society, ruled for hundreds of years by the families that founded it, and the outposts were dependent on the colony’s ties to the Greek mainland for survival.

Even still caked with soil, the exceptional detail of the bronze horseman was evident. It is the only luxury object discovered at this site. Previous finds of ceramics and architectural remains point to a modest settlement founded by Greeks as a defensive outpost of Apollonia. Apollonia was something of an insular society, ruled for hundreds of years by the families that founded it, and the outposts were dependent on the colony’s ties to the Greek mainland for survival.

This suggests that the bronze horseman may also be of Corinthian origin. Corinth was an important center of metalworking in Archaic Greece, and the few horse and rider figures in bronze that are known are believed to have been made in Corinth. The discovery of an exceptional example of a bronze horseman in a remote outpost with almost exclusive links to Corinth supports this hypothesis.

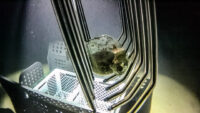

After its discovery, the horseman was kept by the Albanian Institute of Archaeology (AIA) in Tirana for three years. It was still encrusted in soil as it was when it was found. In 2021, the AIA asked the Getty Museum to conserve the object in its state-of-the-art facility. Getty conservators examined the statuette with X-rays and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to learn how it was cast and the metal composition of the bronze. They then focused on removing the dirt, mineral deposits and corrosion materials using miniature scalpels designed as eye surgery tools.

After its discovery, the horseman was kept by the Albanian Institute of Archaeology (AIA) in Tirana for three years. It was still encrusted in soil as it was when it was found. In 2021, the AIA asked the Getty Museum to conserve the object in its state-of-the-art facility. Getty conservators examined the statuette with X-rays and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to learn how it was cast and the metal composition of the bronze. They then focused on removing the dirt, mineral deposits and corrosion materials using miniature scalpels designed as eye surgery tools.

For the most secure possible display, the conservation team created a 3D-printed replica of the statuette to design a bespoke mount that fits the object perfectly. The statuette is now being exhibited on that mount in a case with a dry microclimate to prevent any further corrosion of the metal. The horseman will be at the Getty Villa through January 29th, 2024.