New analyses of the Colchester Vase, a 2nd century clay vessel decorated with scenes of gladiatorial  contests, has confirmed that it was locally made, decorated and inscribed. It was not an import or an object modified with later inscriptions. It was a high-quality piece commemorating a specific gladiatorial event that took place in Colchester.

contests, has confirmed that it was locally made, decorated and inscribed. It was not an import or an object modified with later inscriptions. It was a high-quality piece commemorating a specific gladiatorial event that took place in Colchester.

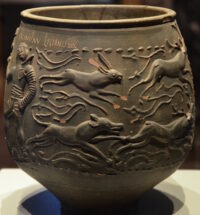

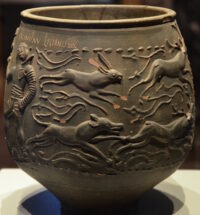

The vase was discovered in a Roman-era grave in West Lodge, Colchester, in 1853. Its format suggests it was more likely a drinking vessel rather than a pitcher or vase, but whatever its original usage, its final use was a cinerary urn. The vessel is nine inches high and is decorated on the outside with three scenes. There are two armed men facing off against each other, two men, one wielding a whip, the other a club, baiting a bear and lastly a hunting dog chasing two stags and a hare. These scenes represent the three types of encounters staged at the arena: men fighting other men, men fighting animals and animals fighting other animals. It is one of the most intricately decorated Roman-era pots ever found in Britain.

The armed men fighting each other can be identified as gladiators by their armature. The one with a short sword (gladius), large rectangular shield (scutus), greaves and a large helmet covering his entire face was a secutor. His opponent, wearing the tall shoulder guard (galerus), arm guard (manica) and loin cloth, is a retiarius or “net fighter.” His trident is on the ground under the secutor’s feet and his finger is raised in the “ad digitum” gesture to acknowledge defeat and request that the munerarius (game director) grant him “missio” (reprieve).

The armed men fighting each other can be identified as gladiators by their armature. The one with a short sword (gladius), large rectangular shield (scutus), greaves and a large helmet covering his entire face was a secutor. His opponent, wearing the tall shoulder guard (galerus), arm guard (manica) and loin cloth, is a retiarius or “net fighter.” His trident is on the ground under the secutor’s feet and his finger is raised in the “ad digitum” gesture to acknowledge defeat and request that the munerarius (game director) grant him “missio” (reprieve).

Four names are incised on the vase: Memnon over the secutor, Valentinus over the retiarius, Secundus and Mario above the bear baiter with the whip. Next to Memnon’s name are the initials SAC and the numeral VIIII, recording that he fought nine times and lived. Next to Valentinus’ name is inscribed LEGIONIS XXX, indicating the retiarius was a soldier in the 30th Legion. This legion was never stationed in Britain.

Four names are incised on the vase: Memnon over the secutor, Valentinus over the retiarius, Secundus and Mario above the bear baiter with the whip. Next to Memnon’s name are the initials SAC and the numeral VIIII, recording that he fought nine times and lived. Next to Valentinus’ name is inscribed LEGIONIS XXX, indicating the retiarius was a soldier in the 30th Legion. This legion was never stationed in Britain.

The uniqueness of the decoration and the reference to a legion that never stepped foot in Britain has spurred debate as to its origin. The clay it was made from was local, but the inscription seemed to point to a foreign hand.

New tests prove the Colchester Vase was made of local clay around AD 160-200 and that an inscription bearing the names of two featured gladiators was cut into the clay before firing, rather than afterwards, as previously assumed. It was therefore an intrinsic part of the vessel’s original design rather than a later addition to a generic arena representation.

That means the vase was the ultimate in sports memorabilia, perhaps commissioned by a gladiator trainer or owner, or someone else involved with such contests.

Frank Hargrave, director of Colchester and Ipswich Museums (CIMS), which owns the vase, told the Observer the research has led to “startling new conclusions”, showing its true significance in recording a real spectacle in Colchester, known to the Romans as Camulodunum.

Frank Hargrave, director of Colchester and Ipswich Museums (CIMS), which owns the vase, told the Observer the research has led to “startling new conclusions”, showing its true significance in recording a real spectacle in Colchester, known to the Romans as Camulodunum.

“It’s the only evidence of a Roman arena gladiator combat actually being staged in Britain,” he said. “There are no written descriptions. The vase is such high quality that there’s been a bit of snobbery, an assumption that it couldn’t possibly have come from Britain, whereas all the analysis has now put that to bed.” […]

Although no amphitheatre – the usual arena for gladiatorial combat – has yet been discovered, Colchester has two Roman theatres where such an event could have been staged. Pearce said: “With our re-analysis of the Colchester Vase, we can be confident that this was an event that took place here.”

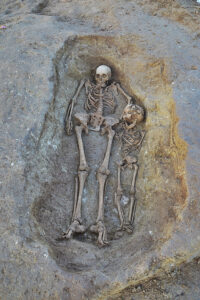

The multidisciplinary research team also studied the cinerary remains found in the urn. Stable isotope analysis revealed the deceased was a non-local male possibly of European origin who was more than 40 years old when he died.

A limestone sphinx from the early Roman Imperial era has been unearthed near the Temple of Hathor in Dendera, 300 miles south of Cairo. The small sphinx was discovered inside a Roman-era shrine. A limestone stele with an inscription written in both hieroglyphics and demotic was found next to the sphinx.

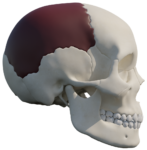

A limestone sphinx from the early Roman Imperial era has been unearthed near the Temple of Hathor in Dendera, 300 miles south of Cairo. The small sphinx was discovered inside a Roman-era shrine. A limestone stele with an inscription written in both hieroglyphics and demotic was found next to the sphinx. The human face on the lion body of the sphinx wears a placid archaic smile with dimples on each side of his lips. He dons the nemes headdress — the striped cloth headdress worn by Egypt’s pharaohs — with the uraeus — the upright cobra that symbolized royal authority — on his forehead. Traces of yellow and red paint have survived on his face.

The human face on the lion body of the sphinx wears a placid archaic smile with dimples on each side of his lips. He dons the nemes headdress — the striped cloth headdress worn by Egypt’s pharaohs — with the uraeus — the upright cobra that symbolized royal authority — on his forehead. Traces of yellow and red paint have survived on his face. With the death of Cleopatra VII, the dynasties of Egyptian pharaohs came to an end. Augustus absorbed Egypt into the Roman Empire but the emperors retained the traditional accoutrements of pharaohs to lend cultural legitimacy to their rules. Roman emperors continued to be styled as Egyptian pharaohs into the 4th century. These iconographic associations were all the more important because most emperors, including Claudius, never visited Egypt in person.

With the death of Cleopatra VII, the dynasties of Egyptian pharaohs came to an end. Augustus absorbed Egypt into the Roman Empire but the emperors retained the traditional accoutrements of pharaohs to lend cultural legitimacy to their rules. Roman emperors continued to be styled as Egyptian pharaohs into the 4th century. These iconographic associations were all the more important because most emperors, including Claudius, never visited Egypt in person.