A double grave from the Late Bronze Age containing three gold and carnelian necklaces has been unearthed at the archaeological site of Metsamor in western Armenia. The skeletal remains of two adults were discovered in a cist (a stone-lined box built into the earth) that also contained the rare remains of a wooden burial bed. The grave dates to 1300–1200 B.C.

A double grave from the Late Bronze Age containing three gold and carnelian necklaces has been unearthed at the archaeological site of Metsamor in western Armenia. The skeletal remains of two adults were discovered in a cist (a stone-lined box built into the earth) that also contained the rare remains of a wooden burial bed. The grave dates to 1300–1200 B.C.

Excavations in the necropolis were carried out in grave No. 23 (chamber dimensions 2.50 x 2.10 m). It is well preserved, covered with a flooring of medium-sized stones. Under it, a burial chamber lined with medium and large stones, oriented from east to west, was unearthed. In the burial chamber on the burial bed, in a twisted state, two human skeletons were found, touching in the area of the pelvic bones. One of the skeletons lay on the right side, the other on the left. In the same layer, 10 solid ceramic vessels were found. Some of the vessels were under the stretcher. As a result of soft tissue rotting, the osteological material ended up on the vessels. In the lower layer, 8 more ceramic items were found, of which the rarest is a small bluish-green glazed vessel with two through holes in the upper part of the body. Cylindrical and spherical beads, bead separators, pendants made of gold, carnelian, amber and tin were found on the neck and chest of the skeletons. Bronze bracelets were found on the wrist of one of them, and tin buckles were found in the abdomen.

A ring made of thin tin wire was found on the wrist of skeleton No. 2. Preliminary research shows that the skeletons of a man and a woman were excavated in the grave chamber. A preliminary study of the archaeological material makes it possible to date the burial to the last quarter of the 2nd millennium BC.

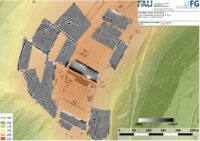

The Bronze Age citadel of Metsamor was built on a hill overlooking the Ararat plain. We don’t know by whom, exactly, as the inhabitants were not literate and left no written documentation behind. In the past decade, a joint team of Polish and Armenian archaeologists excavating the citadel and the lower town have found evidence of occupation in settlements from the Early Bronze Age through the Middle Ages.

When it was at the peak of its population and size in the 4th to the 2nd millennium B.C., the settlement occupied more than 10 hectares and was encircled by cyclopean walls. It continued to expand and grow, reaching nearly 100 hectares in the early Iron Age (11-9th century B.C.). With at least seven temples in the citadel, Metsamor was one of the most important political and cultural centers in the valley.

The necropolis was a third of a mile east of the cyclopean walled perimeter of the settlement. It has been excavated since the 1960s, revealing more than 100 burials from the Middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age. The cist and box graves predominate, but there are also kurgans (burial mounds) and cromlechs (stones arranged in a circular pattern on top of a burial chamber).

The double grave was excavated in the September-October 2022 excavation of the necropolis. The deceased were around 30-40 years old when they died. There is no evidence that the grave was ever reopened, which means the couple died at the same time. There is no obvious cause of death to explain this timing.

The double grave was excavated in the September-October 2022 excavation of the necropolis. The deceased were around 30-40 years old when they died. There is no evidence that the grave was ever reopened, which means the couple died at the same time. There is no obvious cause of death to explain this timing.

The grave is richly appointed and by a lucky break, was never looted in antiquity, a rarity in this context. Only a few of the graves in the necropolis have managed to avoid grave robbers over the millennia, which makes this burial even more significant because of the density of archaeological material that might shed new light on the funerary practices, trade links and lifestyles of Metsamor’s Bronze Age inhabitants.