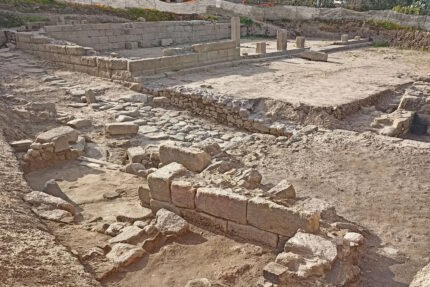

Archaeological excavations at Piazza Pia in Vatican City in anticipation of 2025’s Jubilee Year have uncovered the remains of a colonnaded portico that Caligula built in what had once been his mother’s garden. The remains were found under a later fullonica (laundry) that is being relocated to the nearby Castel Sant-Angelo to make way for a new underpass. The structure consists of a wall of travertine blocks in the opus quadratum (squared) technique terracing the right bank of the Tiber. Behind the wall was the colonnaded portico of which only the foundations remains and a large garden.

Archaeological excavations at Piazza Pia in Vatican City in anticipation of 2025’s Jubilee Year have uncovered the remains of a colonnaded portico that Caligula built in what had once been his mother’s garden. The remains were found under a later fullonica (laundry) that is being relocated to the nearby Castel Sant-Angelo to make way for a new underpass. The structure consists of a wall of travertine blocks in the opus quadratum (squared) technique terracing the right bank of the Tiber. Behind the wall was the colonnaded portico of which only the foundations remains and a large garden.

This was part of the Horti Agrippinae, the gardens of Agrippina the Elder, Caligula’s mother, at her grand suburban villa outside the ancient walls of Rome. Agrippina’s gardens occupied much of today’s Vatican City. Last year archaeologists unearthed the remains of the theater Agrippina’s grandson Nero built on the grounds. Now they’ve found part of the garden Caligula took over.

One lead pipe identifies this as Caligula’s renovation of his mother’s villa and gardens complex. It is stamped “C(ai) Cæsaris Aug (usti) Germanici,” or Caius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the full name of the son of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, grandson of Augustus Caesar. He was known as Caligula after the nickname his father’s soldiers gave him when he was a boy wearing a kid’s version of a military uniform, including the caligae, the hobnailed sandal boots of the legions.

One lead pipe identifies this as Caligula’s renovation of his mother’s villa and gardens complex. It is stamped “C(ai) Cæsaris Aug (usti) Germanici,” or Caius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, the full name of the son of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, grandson of Augustus Caesar. He was known as Caligula after the nickname his father’s soldiers gave him when he was a boy wearing a kid’s version of a military uniform, including the caligae, the hobnailed sandal boots of the legions.

Also from Piazza Pia, but from excavations at the beginning of the last century, come other lead pipes inscribed with the name of Iulia Augusta, presumably Livia Drusilla, the second wife of Augustus and grandmother of Germanicus. It is probable, therefore, that this luxurious residence was first inherited by Germanicus and then, upon his death, to his wife Agrippina the elder and then to his emperor son.

The excavation also revealed an important series of Campana slabs, figurative terracottas used for the decoration of roofs, with unusual mythological scenes, reused as covers for the sewers of the fullonica, but originally probably made for the covering of some structure in the garden, perhaps from the same portico.

There’s a notable reference to Caligula’s use of the Horti Agrippinae in Legatio ad Gaium (The Embassy to Gaius) by Philo of Alexandria, a philosopher and leader of the Jewish community in Alexandria. Philo was one of a delegation of Alexandrian Jews who went to Rome in 39 A.D. to petition for the emperor’s protection after riots targeting Jews in Alexandria the year before had destroyed the synagogues and driven much of the community out of the city. The petition was not ultimately successful, to put it mildly, (Caligula ordered a statue of himself as Jupiter be erected in the Temple in Jerusalem, although he was ultimately talked out of it by his old friend, the last Jewish king of Judea, Herod Agrippa) but the delegation’s first meeting with Caligula seemed to go rather well. From Legatio ad Gaium, XXVIII, 181:

There’s a notable reference to Caligula’s use of the Horti Agrippinae in Legatio ad Gaium (The Embassy to Gaius) by Philo of Alexandria, a philosopher and leader of the Jewish community in Alexandria. Philo was one of a delegation of Alexandrian Jews who went to Rome in 39 A.D. to petition for the emperor’s protection after riots targeting Jews in Alexandria the year before had destroyed the synagogues and driven much of the community out of the city. The petition was not ultimately successful, to put it mildly, (Caligula ordered a statue of himself as Jupiter be erected in the Temple in Jerusalem, although he was ultimately talked out of it by his old friend, the last Jewish king of Judea, Herod Agrippa) but the delegation’s first meeting with Caligula seemed to go rather well. From Legatio ad Gaium, XXVIII, 181:

[R]eceiving us favourably at first, in the plains on the banks of the Tiber (for he happened to be walking about in his mother’s garden), he conversed with us formally, and waved his right hand to us in a protecting manner, giving us significant tokens of his good will, and having sent to us the secretary, whose duty it was to attend to the embassies that arrived, Obulus by name, he said, “I myself will listen to what you have to say at the first favourable opportunity.”

The next time they met was in his palace on the Esquiline and there was no nice walk in mother’s garden and definitely no listening to what they had to say, just a lot of anger about Jews’ refusal to accept Caligula was a god.