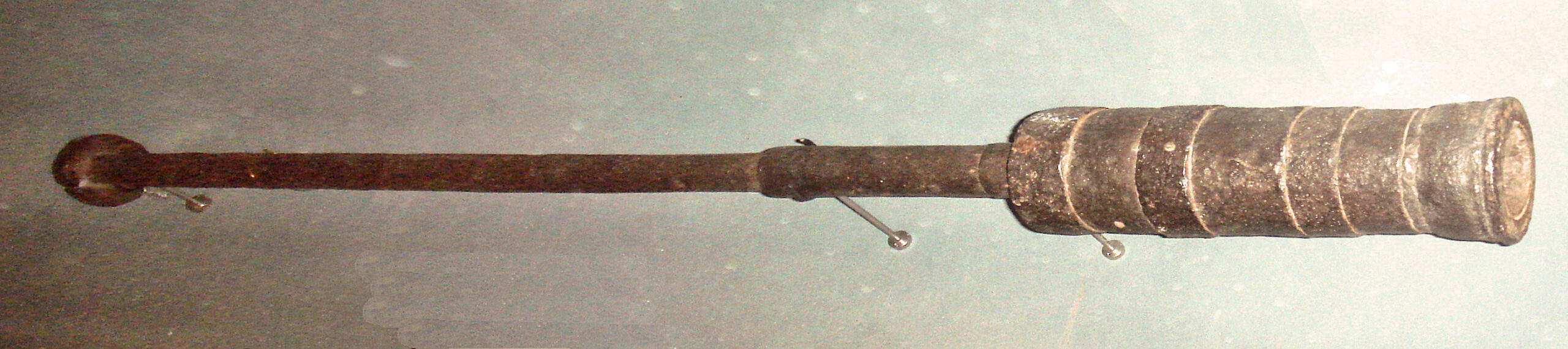

A cylinder of metal bought at a flea market for less than $25 has been identified as an extremely rare medieval hand cannon and sold at auction last Thursday for more than $2,500. The cast bronze cylinder is 17 cm (6.7 inces) long and 4 cm (1.7 inches) wide at its widest end. The bore is 1.7 cm (.7 inches) in diameter. It is a triple-ring cast cannon with a flared muzzle.

A cylinder of metal bought at a flea market for less than $25 has been identified as an extremely rare medieval hand cannon and sold at auction last Thursday for more than $2,500. The cast bronze cylinder is 17 cm (6.7 inces) long and 4 cm (1.7 inches) wide at its widest end. The bore is 1.7 cm (.7 inches) in diameter. It is a triple-ring cast cannon with a flared muzzle.

“It really is a remarkable find,” said Charles [Hanson, owner of Hansons Auctioneers]. “Originally this cannon would have been mounted on wood with a powder bag and ram rod. It evolved to become a match-lock firearm with trigger.

The seller found the bargain of their lifetime at a flea market in Hertfordshire. They spent less than £20 for it, thinking it would make a cool decoration for their garden rockery (which it most certainly would). It was spotted in the rockery by appraisers from Hansons Auctioneers who recognized it as a metal barrel firearm made in Europe between 1400 and 1450.

Gunpowder was invented in China in the 9th century, and weapons that utilized it were widespread by the 12th century. Most of them were forms of bombs, but the fire lance, a spear with a barrel strapped to it capable of firing projectiles, was the precursor to the hand cannon. The oldest confirmed hand cannon, the Heilongjiang hand-gun, dates to 1288. At almost eight pounds, it was a heavy device for a hand weapon and the fire lance remained the more popular firearm until the invention of the musket in the early 16th century.

Gunpowder was invented in China in the 9th century, and weapons that utilized it were widespread by the 12th century. Most of them were forms of bombs, but the fire lance, a spear with a barrel strapped to it capable of firing projectiles, was the precursor to the hand cannon. The oldest confirmed hand cannon, the Heilongjiang hand-gun, dates to 1288. At almost eight pounds, it was a heavy device for a hand weapon and the fire lance remained the more popular firearm until the invention of the musket in the early 16th century.

From China, gunpowder and powder-based weapons migrated to Europe, likely introduced by the Mongols during their invasion of the Turkic states and Eastern Europe in the mid-13th century. The earliest known hand cannon from Europe is the Loshult Gun, a cast bronze gun dating to around 1330-50 discovered in Sweden. Its bottle shape and flared chamber suggests it shot iron bolts or arrows rather than stone or metal balls. It’s also far heavier than the earlier Chinese iterations, weighing in at 22 pounds.

The first written record of hand cannons in England dates to 1473, but there are records of their use in France in the late 14th century and surviving examples going back to the 1380s. The Hundred Years’ War saw to it that the English were thoroughly exposed to the latest and greatest weaponry available in France. The rock garden hand cannon predates the English written account and is closer in age to the French examples.