One of the 14th century painted burial vaults discovered last year under the street in front of the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, Belgium, has been lifted whole and moved to a new location for conservation and eventual display. Similar vaults found before in Bruges were filled with lightweight clay aggregates to preserve the interior wall paintings and reburied for their own protection, but the most recent discoveries have to be moved due to the planned construction of a new pumping station on the street where they were found.

One of the 14th century painted burial vaults discovered last year under the street in front of the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, Belgium, has been lifted whole and moved to a new location for conservation and eventual display. Similar vaults found before in Bruges were filled with lightweight clay aggregates to preserve the interior wall paintings and reburied for their own protection, but the most recent discoveries have to be moved due to the planned construction of a new pumping station on the street where they were found.

Raising a 700-year-old masonry vault presents numerous logistical challenges. They were built to order, as it were, hastily constructed so that a body could be buried within 24 hours of death. The lime plaster coating the interior was painted when still wet and quickly sealed. Past attempts to raise burial vaults have failed and damaged the priceless paintings, so the City of Bruges created a multi-disciplinary committee of scientists, archaeologists and specialist conservators to coordinate the removal of the best-preserved vault first.

Raising a 700-year-old masonry vault presents numerous logistical challenges. They were built to order, as it were, hastily constructed so that a body could be buried within 24 hours of death. The lime plaster coating the interior was painted when still wet and quickly sealed. Past attempts to raise burial vaults have failed and damaged the priceless paintings, so the City of Bruges created a multi-disciplinary committee of scientists, archaeologists and specialist conservators to coordinate the removal of the best-preserved vault first.

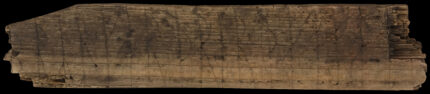

The wall paintings were fixed using Japanese rice paper to prevent plaster loss. While conservators were working on the interior, the exterior base was reinforced with a new poured concrete slab to make it possible to lift the entire vault even in cold, wet and windy weather without the bottom falling out of it.

The vault is now inside the Church of Our Lady where it will be meticulously conserved. The restoration process begins with a controlled drying period. It is a Goldilocks situation. The temperature and humidity levels must be strictly maintained to ensure the tomb doesn’t dry too quickly (because the paint will flake off the contracting walls) or too slowly (because mold will form).

The vault is now inside the Church of Our Lady where it will be meticulously conserved. The restoration process begins with a controlled drying period. It is a Goldilocks situation. The temperature and humidity levels must be strictly maintained to ensure the tomb doesn’t dry too quickly (because the paint will flake off the contracting walls) or too slowly (because mold will form).

It will be conserved in public view, pandemic permitting, in the church museum where it will go on permanent display when the restoration is complete.

Here’s a time-lapse video of conservators working on the vault before it was raised.