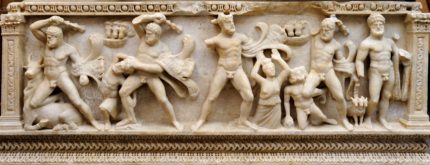

A Roman-era marble sarcophagus decorated with a bas relief of the Twelve Labors of Hercules on its sides has returned to Turkey after a long sojourn in the at haven of looted antiquities smuggling that is the Geneva Free Port. The saga begins on December 3rd, 2010, when the 2nd century A.D. sarcophagus was discovered in one of the Free Port warehouses by customs officials during an inventory check. Measuring 7.7 x 3.7 feet and weighing three tons, the sarcophagus is actually on the smaller side for its type, but it’s still hard to miss as a suspect antiquity, even hidden under piles of blankets and boxes.

This type of sarcophagus was a popular consumer good, produced on a large scale in workshops in Dokimenion (modern-day Iscehisar, western Turkey) from locally quarried marble in the second half of the second century. They weren’t all cookie-cutter pieces, however. Some are distinctly better than others, commissioned by people who could afford the highest reliefs, the most prized marble and the greatest sculptors. This sarcophagus is the best of all the surviving examples, with top-notch carving depth and anatomical detail. A very wealthy person must have commissioned it.

This type of sarcophagus was a popular consumer good, produced on a large scale in workshops in Dokimenion (modern-day Iscehisar, western Turkey) from locally quarried marble in the second half of the second century. They weren’t all cookie-cutter pieces, however. Some are distinctly better than others, commissioned by people who could afford the highest reliefs, the most prized marble and the greatest sculptors. This sarcophagus is the best of all the surviving examples, with top-notch carving depth and anatomical detail. A very wealthy person must have commissioned it.

After years of being used as a pivot for the illicit trade in antiquities thanks to its no questions asked approached and tax-free Geneva warehouse complex, Switzerland was now taking a different approach. In 2003, it finally ratified the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. In 2005 it passed a law requiring that all objects of cultural patrimony had to have verified ownership records. In 2009, a new law forced international traders in cultural goods to file complete and accurate inventories. This law had teeth too, with funding for a customs notification system and thorough inspection of the goods stashed in Free Port warehouses.

So when the sarcophagus’ so-called owner, Phoenix Ancient Art, an antiquities dealership co-owned by brothers Ali and Hicham Aboutaam who have been involved in many, many highly questionable transactions of looted artifacts, was unable to provide proper documentation in compliance with Switzerland’s more stringent regulation, the object was sequestered. Ali protested vociferously. He insisted it had belonged, like all of his loot, to his father who had bought it legally in the 1990s. He fought all attempts at restitution, and the case dragged through the courts for six years.

So when the sarcophagus’ so-called owner, Phoenix Ancient Art, an antiquities dealership co-owned by brothers Ali and Hicham Aboutaam who have been involved in many, many highly questionable transactions of looted artifacts, was unable to provide proper documentation in compliance with Switzerland’s more stringent regulation, the object was sequestered. Ali protested vociferously. He insisted it had belonged, like all of his loot, to his father who had bought it legally in the 1990s. He fought all attempts at restitution, and the case dragged through the courts for six years.

A joint investigation by Swiss and Turkish authorities found that the sarcophagus had likely been looted from the ancient site of Perge in Antalya during an illegal excavation in the 1970s. This was confirmed by soil and marble analyses. How it wound its way from Turkey to Switzerland remains unclear and the Aboutaam’s father Sleiman died in 1998 so he can’t answer any questions. He also can’t be prosecuted. On September 21st, 2015, a Swiss prosecutor issued an order that the sarcophagus be restituted to Turkey. The Aboutaam’s appealed twice before withdrawing the last appeal in March 2016. That left the restitution order as the final legal say in the matter, and all that was left was for the slow grind of the legal grist mill to finish its work before the piece was returned. Culture and Tourism Ministry officials in Geneva received the sarcophagus on September 13th. It was in Turkey on September 14th.

After almost seven years of legal wrangling, detective work and waiting, the Hercules sarcophagus was welcomed to its new home, the Antalya Museum, on Sunday in an unveiling ceremony presided over by Culture and Tourism Minister Numan Kurtulmuş. It is now on display next to the Weary Herakles, a Roman copy in marble of a 4th century B.C. original bronze by the Greek sculptor Lysippos of Sikyon, which was also looted from Perge and whose torso was pried out of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts after a lengthy battle so it could be reunited with the legs already on display the museum.

After almost seven years of legal wrangling, detective work and waiting, the Hercules sarcophagus was welcomed to its new home, the Antalya Museum, on Sunday in an unveiling ceremony presided over by Culture and Tourism Minister Numan Kurtulmuş. It is now on display next to the Weary Herakles, a Roman copy in marble of a 4th century B.C. original bronze by the Greek sculptor Lysippos of Sikyon, which was also looted from Perge and whose torso was pried out of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts after a lengthy battle so it could be reunited with the legs already on display the museum.