The Nymphaeum of the Rain, a frescoed semi-subterranean leisure room in the Farnese Gardens on the Palatine in Rome, has been restored and reopened to the public after decades of closure. Now visitors will be able to enjoy the cultural context of Baroque Rome on the Palatine even as they enjoy the its ancient culture with the reopening of the Domus Tiberiana.

The Nymphaeum of the Rain, a frescoed semi-subterranean leisure room in the Farnese Gardens on the Palatine in Rome, has been restored and reopened to the public after decades of closure. Now visitors will be able to enjoy the cultural context of Baroque Rome on the Palatine even as they enjoy the its ancient culture with the reopening of the Domus Tiberiana.

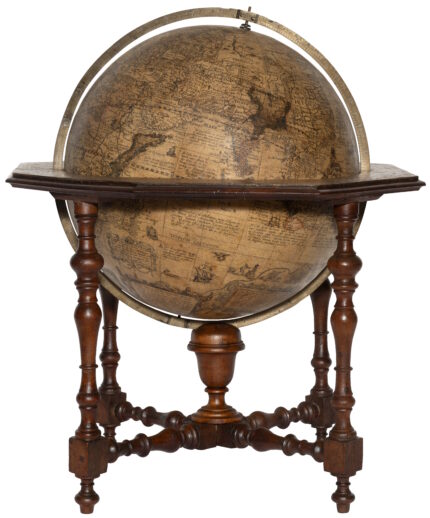

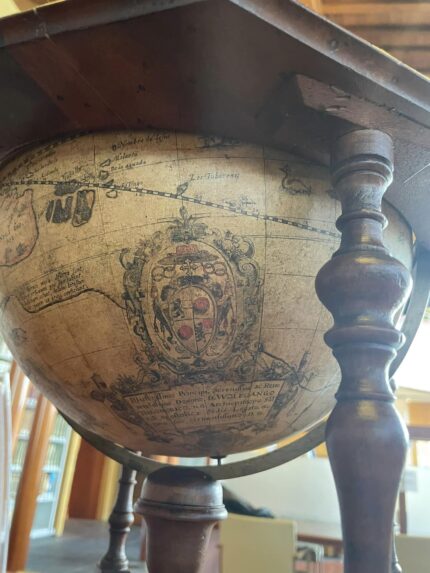

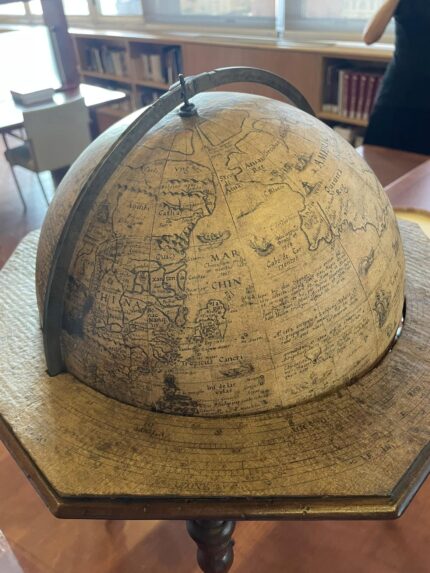

Built in the second half of the 16th century by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, the Farnese Gardens were the first private botanical gardens in Europe. The Nymphaeum of the Rain was built on the northern slope of the Palatine in the 1600s. was commissioned by Cardinal Odoardo Farnese as a “summer triclinium,” a refuge from the heat of summer in Rome to sup and contemplate surrounded by a fine collection of ancient sculptures.

It was his heir, also named Odoardo, who transformed it into a far grander space. The terraces and staircases topped by the twin aviaries, the remains of which are all that remains of the much larger Farnese Gardens, were built at Odoardo’s request by the family architect Girolamo Rainaldi. The cardinal’s old “triclinium” was turned into a sumptuous nymphaeum, inspired by the nymphaea of ancient Rome and Greece, natural or artificial grottoes used as sanctuaries to the water nymphs and as refreshing assembly rooms for recreation.

It was his heir, also named Odoardo, who transformed it into a far grander space. The terraces and staircases topped by the twin aviaries, the remains of which are all that remains of the much larger Farnese Gardens, were built at Odoardo’s request by the family architect Girolamo Rainaldi. The cardinal’s old “triclinium” was turned into a sumptuous nymphaeum, inspired by the nymphaea of ancient Rome and Greece, natural or artificial grottoes used as sanctuaries to the water nymphs and as refreshing assembly rooms for recreation.

In the summer heat, he would welcome guests for parties and concerts into the cool, shady freshness of the nymphaeum. Its fountain, artfully designed to look like a stalactite formation employed a complex series of pipes to move water from the main fountain of the garden through limestone rocks, faux stalactites and seven metal trays from which numerous jets sprang, recreating the sights and sounds of natural rainfall inside the nymphaeum. Baroque artist Giovan Battista Magni, known as il Modanino (1591/92-1674), decorated the walls and ceilings with climbing vines and created the illusion of an opening at the top of the ceiling where birds, grape vines and musicians adorn an arched balustrade looking down at the assembled visitors below.

In the summer heat, he would welcome guests for parties and concerts into the cool, shady freshness of the nymphaeum. Its fountain, artfully designed to look like a stalactite formation employed a complex series of pipes to move water from the main fountain of the garden through limestone rocks, faux stalactites and seven metal trays from which numerous jets sprang, recreating the sights and sounds of natural rainfall inside the nymphaeum. Baroque artist Giovan Battista Magni, known as il Modanino (1591/92-1674), decorated the walls and ceilings with climbing vines and created the illusion of an opening at the top of the ceiling where birds, grape vines and musicians adorn an arched balustrade looking down at the assembled visitors below.

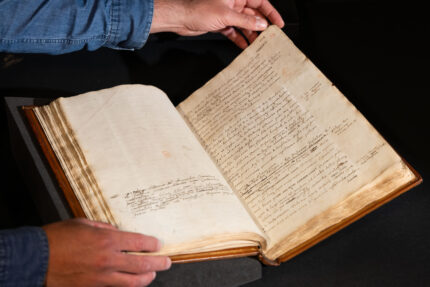

The garden fell into neglect and disrepair in the 18th century and when it was acquired by the newly-unified Italy in 1870, much of what remains was demolished to excavate the ancient palace underneath it. The very top of the terraced garden, including the nymphaeum, survived, but in parlous condition. The frescoes were lost, faded or plastered over, and only rediscovered at the end of the 1950s. For decades it has been too unstable, suffering greatly from moisture penetration, to allow tourists to get a glimpse of its frescoed plaster walls and ceiling framing the elaborate Fountain of the Rain.

The garden fell into neglect and disrepair in the 18th century and when it was acquired by the newly-unified Italy in 1870, much of what remains was demolished to excavate the ancient palace underneath it. The very top of the terraced garden, including the nymphaeum, survived, but in parlous condition. The frescoes were lost, faded or plastered over, and only rediscovered at the end of the 1950s. For decades it has been too unstable, suffering greatly from moisture penetration, to allow tourists to get a glimpse of its frescoed plaster walls and ceiling framing the elaborate Fountain of the Rain.

The Archaeological Park of the Colosseum embarked on a major conservation project to restore the Nymphaeum in 2020. It took three years to repair the water infiltration problem and restore the damaged structure. The Fountain of the Rain has been restored to its original design, with its hydraulic system of seven different metal trays of different size that replicated the sound of rain and its fake stalactites. The restoration of the full frescoes with its climbing vines and musicians looking down on the room from the ceiling sheds new light on the original function of the space, a faux garden pergola where music, poetry and the arts were enjoyed in an environment of simulated nature and ancient influence.

The Archaeological Park of the Colosseum embarked on a major conservation project to restore the Nymphaeum in 2020. It took three years to repair the water infiltration problem and restore the damaged structure. The Fountain of the Rain has been restored to its original design, with its hydraulic system of seven different metal trays of different size that replicated the sound of rain and its fake stalactites. The restoration of the full frescoes with its climbing vines and musicians looking down on the room from the ceiling sheds new light on the original function of the space, a faux garden pergola where music, poetry and the arts were enjoyed in an environment of simulated nature and ancient influence.