In 1995, an archaeological excavation under the Wheelwright’s Shop of Chatham Historic Dockyard in Kent discovered that 167 timbers from a warship had been recycled as floor joists. Many of the great wooden ships of the British Navy during the Age of Sail in the 18th and early 19th centuries had been built at Chatham, most famously Admiral Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory, but it came as a surprise to find a ship had returned the favor and built part of the dockyard.

In 1995, an archaeological excavation under the Wheelwright’s Shop of Chatham Historic Dockyard in Kent discovered that 167 timbers from a warship had been recycled as floor joists. Many of the great wooden ships of the British Navy during the Age of Sail in the 18th and early 19th centuries had been built at Chatham, most famously Admiral Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory, but it came as a surprise to find a ship had returned the favor and built part of the dockyard.

The wine-glass shape of the beams is characteristic of a sailing warship’s hull, and the quantity of timber indicated that it had come from a second- or third-rate ship of the line. There were carpenters’ marks on some of the beams which were identifiable as the signatures of workers at the Chatham Royal Dockyard, some of whom had left the same marks on timber in the hull of HMS Victory. It was clear from the historical layers that the floor was not original to the Wheelwright’s Shop when it was first built in the 1780s, but rather was installed during major alterations to the space done in the 1830s.

The wine-glass shape of the beams is characteristic of a sailing warship’s hull, and the quantity of timber indicated that it had come from a second- or third-rate ship of the line. There were carpenters’ marks on some of the beams which were identifiable as the signatures of workers at the Chatham Royal Dockyard, some of whom had left the same marks on timber in the hull of HMS Victory. It was clear from the historical layers that the floor was not original to the Wheelwright’s Shop when it was first built in the 1780s, but rather was installed during major alterations to the space done in the 1830s.  A key clue was the curve to some of the timbers, indicative of the “round bow” design by naval architect Robert Seppings who was promoted to master shipwright at Chatham in 1804 after the success of his round bow and stern innovations.

A key clue was the curve to some of the timbers, indicative of the “round bow” design by naval architect Robert Seppings who was promoted to master shipwright at Chatham in 1804 after the success of his round bow and stern innovations.

So historians were looking for a second- or third-rate ship of the line built at Chatham between 1750 and 1775, repaired at Chatham and thus still in sailing form in 1804, then broken up in time for reuse in the early 1830s. It took them 17 years to conclusively identify it, but there’s only one ship that fits all the clues: it was HMS Namur, a 90-gun second-rate ship of the line that saw an extraordinary amount of action at some of Britain’s most important sea battles between her launch in 1756 and her dismantling in 1833.

The Seven Years War started in 1756, and the Namur played a major role at the Siege of Fort Louisbourg in 1758, which opened the rest of Canada to British attack; the Battle of Lagos in 1759, which kneecapped France’s planned invasion of England; and the Capture of Havana in 1762, which ended Spanish naval dominance in the West Indies. Namur also fought against the Spanish and French during the American War of Independence, defeating the former at the Second Relief of Gibraltar on April 4th, 1781, then whupping the latter at the Battle of the Saintes almost exactly a year later. Even though she was getting on in years by then, HMS Namur still fought valiantly against the French in the Napoleonic Wars, including at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797 and in Strachan’s cleanup action after Trafalgar in 1805.

The Seven Years War started in 1756, and the Namur played a major role at the Siege of Fort Louisbourg in 1758, which opened the rest of Canada to British attack; the Battle of Lagos in 1759, which kneecapped France’s planned invasion of England; and the Capture of Havana in 1762, which ended Spanish naval dominance in the West Indies. Namur also fought against the Spanish and French during the American War of Independence, defeating the former at the Second Relief of Gibraltar on April 4th, 1781, then whupping the latter at the Battle of the Saintes almost exactly a year later. Even though she was getting on in years by then, HMS Namur still fought valiantly against the French in the Napoleonic Wars, including at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797 and in Strachan’s cleanup action after Trafalgar in 1805.

All told, Namur put in an exceptional 47 years of active service in the Royal Navy and 28 more on guard duty. Most ships from this period had a working life of around 20 years. In 1805 she had her decks shaved down, leaving her a 74-gun ship, and in 1807 was deployed to the east coast of England on harbor service at the Nore, a sandbank in the Thames Estuary which was once the scene of a spectacular kicking of England’s ass by the Dutch. There she remained until her honorable demise in 1833.

All told, Namur put in an exceptional 47 years of active service in the Royal Navy and 28 more on guard duty. Most ships from this period had a working life of around 20 years. In 1805 she had her decks shaved down, leaving her a 74-gun ship, and in 1807 was deployed to the east coast of England on harbor service at the Nore, a sandbank in the Thames Estuary which was once the scene of a spectacular kicking of England’s ass by the Dutch. There she remained until her honorable demise in 1833.

As much as it seems the European powers did nothing but fight on sea and land during this period, it was actually rare for any given ship to see a battle at all. The Namur saw nine, of which seven were of decisive importance in establishing and maintaining Britain’s command of the oceans.

As if that weren’t enough of a claim to fame, HMS Namur was also home to two figures known to history for reasons beyond only their naval roles. Between 1811 and 1814, HMS Namur was captained by one Charles Austen, future Rear Admiral and brother of novelist Jane Austen. She wove the naval experiences of Charles and their elder brother Francis, future Admiral of the Fleet, into several of her works, including Mansfield Park and my personal favorite, Persuasion, her last novel wherein naval officers are central characters and society’s reaction to the new prominence of the navy a central theme.

As if that weren’t enough of a claim to fame, HMS Namur was also home to two figures known to history for reasons beyond only their naval roles. Between 1811 and 1814, HMS Namur was captained by one Charles Austen, future Rear Admiral and brother of novelist Jane Austen. She wove the naval experiences of Charles and their elder brother Francis, future Admiral of the Fleet, into several of her works, including Mansfield Park and my personal favorite, Persuasion, her last novel wherein naval officers are central characters and society’s reaction to the new prominence of the navy a central theme.

Olaudah Equiano, former slave, merchant and author of the first slave narrative, worked on board the Namur in 1759 during the Battle of Lagos. He was a boy of around 14 and had been enslaved since he was kidnapped at 11 years of age. His owner in 1759 was Michael Henry Pascal, the 4th lieutenant on HMS Namur. Pascal put Equiano to work as a powder monkey, a dangerous job that entailed carrying gunpowder from the magazine to the gunners. Children were assigned to the task because they were small and could hide behind the gunwale when enemy sharpshooters aimed for them.

Olaudah Equiano, former slave, merchant and author of the first slave narrative, worked on board the Namur in 1759 during the Battle of Lagos. He was a boy of around 14 and had been enslaved since he was kidnapped at 11 years of age. His owner in 1759 was Michael Henry Pascal, the 4th lieutenant on HMS Namur. Pascal put Equiano to work as a powder monkey, a dangerous job that entailed carrying gunpowder from the magazine to the gunners. Children were assigned to the task because they were small and could hide behind the gunwale when enemy sharpshooters aimed for them.

Equiano’s autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, published in 1789, was a smash hit and played a pivotal role in the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807. He describes his experiences aboard the Namur in chapters three and four, with the Battle of Lagos featured in the latter.

This series of accomplishments, impressive though they may be, could not keep HMS Namur from returning to her birthplace at the Royal Dockyard in Chatham for dismantling in 1833. Somebody there, however, and we don’t know for sure who or why, saw fit to keep part of the legend alive by using large hull timbers and planking to make a new floor for the Wheelwright’s Shop during renovations in 1834. The long, strong beams from the hull support the full width of the floor and are of obvious structural use, but there are also smaller planks laid flat between the joists. Why include them at all?

This series of accomplishments, impressive though they may be, could not keep HMS Namur from returning to her birthplace at the Royal Dockyard in Chatham for dismantling in 1833. Somebody there, however, and we don’t know for sure who or why, saw fit to keep part of the legend alive by using large hull timbers and planking to make a new floor for the Wheelwright’s Shop during renovations in 1834. The long, strong beams from the hull support the full width of the floor and are of obvious structural use, but there are also smaller planks laid flat between the joists. Why include them at all?

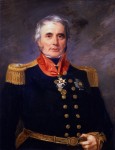

One possible answer is James Alexander Gordon, the Dockyard Captain Superintendent in 1834. Gordon had risen from Midshipman to Admiral of the Fleet, serving an unprecedented 75 years in the Royal Navy. He is thought to have been one of the inspirations for Horatio Hornblower, C.S. Forester’s fictional naval hero. In 1786, when Gordon was 14 years old (he had already been in the navy for three years by then, believe it or not), he served on HMS Namur as a midshipman. He saw action aboard the Namur at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797. It’s possible that he felt a sentimental attachment to the old bucket and saw to it that she would continue to sustain the Royal Navy in a new position: namely, as a floor.

One possible answer is James Alexander Gordon, the Dockyard Captain Superintendent in 1834. Gordon had risen from Midshipman to Admiral of the Fleet, serving an unprecedented 75 years in the Royal Navy. He is thought to have been one of the inspirations for Horatio Hornblower, C.S. Forester’s fictional naval hero. In 1786, when Gordon was 14 years old (he had already been in the navy for three years by then, believe it or not), he served on HMS Namur as a midshipman. He saw action aboard the Namur at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797. It’s possible that he felt a sentimental attachment to the old bucket and saw to it that she would continue to sustain the Royal Navy in a new position: namely, as a floor.

Doubtless Gordon would have been proud to see that floor become the centerpiece of a multi-million dollar redevelopment of the Historic Dockyard Chatham which, in addition to creating a new visitor center and a Command of the Oceans gallery detailing the history of the dockyard during the Age of Sail, will also be dedicated to long-term conservation of the Namur warship timbers. The Heritage Lottery Fund has granted Chatham £4.5 million ($7,140,000) in matching funds, but the dockyard has to raise £4 million ($6,350,000) within 15 months to secure the grant.

Doubtless Gordon would have been proud to see that floor become the centerpiece of a multi-million dollar redevelopment of the Historic Dockyard Chatham which, in addition to creating a new visitor center and a Command of the Oceans gallery detailing the history of the dockyard during the Age of Sail, will also be dedicated to long-term conservation of the Namur warship timbers. The Heritage Lottery Fund has granted Chatham £4.5 million ($7,140,000) in matching funds, but the dockyard has to raise £4 million ($6,350,000) within 15 months to secure the grant.

If you’d like to chip in, you can donate online to the Command of the Oceans project here. You can also mail checks to the address listed on this page and if you’re in Britain, you can send £3 that will go directly to the preservation of the timbers by texting “SHIP01 £3” to 70070.