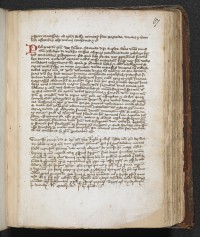

The transcript of a previously unknown letter written by Robert the Bruce of Scotland to King Edward II in October of 1310 has been discovered in a British Library manuscript. Previously attributed to Robert II, the Bruce’s son-in-law and king of Scotland from 1371 to 1390, the letter was included in a scrapbook of sorts, a compendium of poems, histories, legends, medicinal recipes, chronicles and correspondence compiled by the Cistercian monks of Kirkstall Abbey in Leeds, Yorkshire, in the late 15th, early 16th century. The correspondence section was apparently copied from a dossier of letters between King Edward III of England, Pope Benedict XII, Pope Clement VI, Philippe VI of France, John Stratford, the archbishop of Canterbury, emperor Ludwig of Bavaria and the Duke of Guelders.

The transcript of a previously unknown letter written by Robert the Bruce of Scotland to King Edward II in October of 1310 has been discovered in a British Library manuscript. Previously attributed to Robert II, the Bruce’s son-in-law and king of Scotland from 1371 to 1390, the letter was included in a scrapbook of sorts, a compendium of poems, histories, legends, medicinal recipes, chronicles and correspondence compiled by the Cistercian monks of Kirkstall Abbey in Leeds, Yorkshire, in the late 15th, early 16th century. The correspondence section was apparently copied from a dossier of letters between King Edward III of England, Pope Benedict XII, Pope Clement VI, Philippe VI of France, John Stratford, the archbishop of Canterbury, emperor Ludwig of Bavaria and the Duke of Guelders.

The Bruce letter comes early in this correspondence series which is why a 19th century cataloger assumed it was from Robert II to Edward III. When University of Glasgow Professor Dauvit Broun came across the letter while doing research for the Breaking of Britain, a project examining Scottish independence from 1216 through Robert the Bruce’s victory at Bannockburn in 1314, he realized that there was no way the letter was written by Robert II. The context was all wrong. The letter is dated October 1st, “in the fifth year of our reign,” which under Robert II would have been 1375. However, Scotland and England weren’t at war in 1375. Robert II and Edward III had signed a truce in 1370 and it lasted for 14 years. The only way this letter makes sense is if it was written by Robert I.

Here is the English translation of the letter (originally written in Latin):

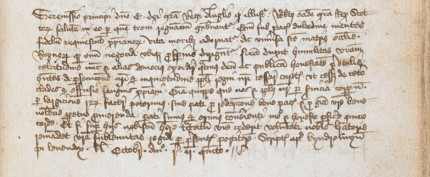

To the most serene prince the lord Edward by God’s grace illustrious king of England, Robert by the same grace king of Scots, greeting in Him through whom the thrones of those who rule are governed. When, under the sweetness of peace, the minds of the neighbouring faithful find rest, then life is adorned with good conduct, and also the whole of Holy Mother Church, because the affairs of kingdoms are everywhere arranged more favourably by everyone. Our humbleness has led us, now and at other times, to beseech your highness more devoutly so that, having God and public decency in sight, you would take pains to cease from our persecution and the disturbance of the people of our kingdom in order that devastation and the spilling of a neighbour’s blood may henceforth stop. Naturally, everything which we and our people will be able to do by bodily service, or to bear by giving freely of our goods, for the redemption of good peace and for the perpetually flourishing grace of your good will, we are prepared and shall be prepared to accomplish in a suitable and honest way, with a pure heart. And if it accords with your will to have a discussion with us on these matters, may your royal sublimity send word in writing to us, by the bearer of this letter. Written at Kildrum in Lennox, the Kalends of October in the fifth year of our reign.

Edward II and a large army were in Scotland in October of 1310. The Bruce had been accumulating military successes since 1307, harrying the British with guerrilla warfare tactics. Edward, encamped in Biggar, south Scotland, hoped to entice Robert into a pitched battle where his troops would dominate. Kildrum (today part of Cumbernauld) was a town just a day’s horse ride away from Biggar. It follows that Robert, having heard of Edward’s army movements, sent the letter in an attempt to stop the British advance into Scotland.

With a British army in his territory spoiling for a fight, it’s no surprise that Robert takes an extremely conciliatory approach in this letter, addressing Edward in glowing terms while emphasizing his own humility. At the same time, he makes it clear that this is a king-to-king conversation, that Robert governs Scotland with the exact same legitimacy with which Edward governs England. The recognition of Scotland as a separate and independent kingdom is the underlying premise of the letter. England’s disagreement on this point is the reason there’s a war at all, so even though Robert appears to bow and scrape offering to do anything for peace, in fact he’s asserting his right and his rule in no uncertain terms.

Robert may also have been hoping to draw out the confrontation past fighting season. October is not a good time to start a military campaign in Scotland. A few months of back-and-forth messaging and negotiations would at least postpone the war until the next year. In fact, by December, Edward II sent negotiators to talks with Robert I at Selkirk. Historians have assumed that Edward initiated the talks, but this letter is strong evidence that Robert opened the door that Edward would walk through two months later.

The negotiations ultimately went nowhere. A follow-up meeting between Robert and Edward’s emissaries fell through when Robert failed to show up, possibly because he feared an ambush, but perhaps because he just wasn’t into it anymore. In October, the prospect of an overwhelming British invasion force loomed. Two months later, the immediate danger had passed.