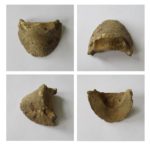

Argentina’s federal police and Interpol discovered a secret cache of Nazi artifacts in a Buenos Aires home earlier this month. It was an accidental find. The police were looking for smuggled Chinese art, antiquities and mummies but instead found around 75 Nazi objects in a room at the end of a secret passageway whose entrance was hidden behind a bookshelf. The collection is varied but appears to be of very high end material — magnifying glasses, telescopes, firearms, medals, an award from Krupp, a Reichsadler (imperial eagle) manufactured by Carl Eickhorn of Solingen, busts and reliefs of Hitler, a presentation dagger with carved antler handle and swastika medallion, swastika-branded toys like board games and harmonicas to help raise good Nazi children. It is the largest collection of Nazi tat ever found in Argentina.

Argentina’s federal police and Interpol discovered a secret cache of Nazi artifacts in a Buenos Aires home earlier this month. It was an accidental find. The police were looking for smuggled Chinese art, antiquities and mummies but instead found around 75 Nazi objects in a room at the end of a secret passageway whose entrance was hidden behind a bookshelf. The collection is varied but appears to be of very high end material — magnifying glasses, telescopes, firearms, medals, an award from Krupp, a Reichsadler (imperial eagle) manufactured by Carl Eickhorn of Solingen, busts and reliefs of Hitler, a presentation dagger with carved antler handle and swastika medallion, swastika-branded toys like board games and harmonicas to help raise good Nazi children. It is the largest collection of Nazi tat ever found in Argentina.

Officials believe these pieces may have entered Argentina with one of the high-ranking Nazi officials who traveled to the country either during the party’s heyday or who fled there after Germany’s defeat. The monster/doctor Josef Mengele who used Auschwitz inmates as guinea pigs in his sickening and usually fatal experiments lived in Buenos Aires for more than a decade from 1949 until 1960. Adolf Eichmann, one of the main architects of the Holocaust who was “just following orders,” was captured by Mossad agents in Buenos Aires in 1960, tried in Israel, convicted and executed. The home where the secret trove was found is in Beccar, a northern suburb of Buenos Aires. Both Mengele and Eichmann lived in Beccar during their sojourns in the Argentinian capital.

Officials believe these pieces may have entered Argentina with one of the high-ranking Nazi officials who traveled to the country either during the party’s heyday or who fled there after Germany’s defeat. The monster/doctor Josef Mengele who used Auschwitz inmates as guinea pigs in his sickening and usually fatal experiments lived in Buenos Aires for more than a decade from 1949 until 1960. Adolf Eichmann, one of the main architects of the Holocaust who was “just following orders,” was captured by Mossad agents in Buenos Aires in 1960, tried in Israel, convicted and executed. The home where the secret trove was found is in Beccar, a northern suburb of Buenos Aires. Both Mengele and Eichmann lived in Beccar during their sojourns in the Argentinian capital.

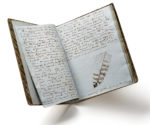

The name of the homeowner has not been released. All the authorities will say about this individual is that he is a collector who claims to have acquired the Nazi memorabilia in a single purchase 25 years ago from an Argentinian national. He has an eclectic group of 17 different collections, including a collection of erotica which features highly decorative Russian dildos from the Tsarist era. The collector has yet to be charged for any crime, but he is accused of smuggling (charges unrelated to the Nazi artifacts) and is being investigated for illegal sale of Nazi propaganda. He insists he wasn’t selling any of those objects and his ownership of them is not against the law.

The name of the homeowner has not been released. All the authorities will say about this individual is that he is a collector who claims to have acquired the Nazi memorabilia in a single purchase 25 years ago from an Argentinian national. He has an eclectic group of 17 different collections, including a collection of erotica which features highly decorative Russian dildos from the Tsarist era. The collector has yet to be charged for any crime, but he is accused of smuggling (charges unrelated to the Nazi artifacts) and is being investigated for illegal sale of Nazi propaganda. He insists he wasn’t selling any of those objects and his ownership of them is not against the law.

Meanwhile, the objects have yet to be authenticated. No matter what he was doing with them, if they’re fakes, it’s not illegal even if he was trying to sell them. The police have called in historians to study the pieces and help determine their origin.

“Our first investigations indicate that these are original pieces,” Argentine Security Minister Patricia Bullrich told The Associated Press on Monday, saying that some pieces were accompanied by old photographs. “This is a way to commercialize them, showing that they were used by the horror, by the Fuhrer. There are photos of him with the objects.” […]

Police say one of the most-compelling pieces of evidence of the historical importance of the find is a photo negative of Hitler holding a magnifying glass similar to those found in the boxes.

“We have turned to historians and they’ve told us it is the original magnifying glass” that Hitler was using, said Nestor Roncaglia, head of Argentina’s federal police. “We are reaching out to international experts to deepen” the investigation.

Militaria expert and appraiser Bill Panagopulos of Alexander Historical Auctions disputes the police’s initial conclusions in the strongest possible terms, calling the objects “carnival-quality garbage” and “a bunch of ersatz liverwurst.”

Militaria expert and appraiser Bill Panagopulos of Alexander Historical Auctions disputes the police’s initial conclusions in the strongest possible terms, calling the objects “carnival-quality garbage” and “a bunch of ersatz liverwurst.”

There’s no question that authentication is going to be challenging, if not impossible. The Eickhorn company still exists today in Solingen, for example, but their records are patchy thanks to the disruption of war and several subsequent bankruptcies. They found nothing in the archives matching the Eickhorn pieces found in Buenos Aires, and counterfeits abound.

Once the investigation is complete, the plan is to give the artifacts to the Holocaust Museum of Buenos Aires. Whether this actually happens remains to be seen. If they prove to be fakes, the museum may not be interested, and even if they are authentic, this could well end up in civil court if the collector files a claim of legitimate ownership.

Once the investigation is complete, the plan is to give the artifacts to the Holocaust Museum of Buenos Aires. Whether this actually happens remains to be seen. If they prove to be fakes, the museum may not be interested, and even if they are authentic, this could well end up in civil court if the collector files a claim of legitimate ownership.