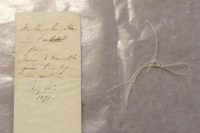

The small, purplish spindle whorl was unearthed by archaeologists in Czermno, Poland, in 1952. What the people who found it didn’t realize is that the biconical slate piece was inscribed, making it a unique find in the Polish archaeological record. It was Iwona Florkiewicz from the Institute of Archeology of the University of Rzeszów who discovered how precious this little piece really during an inventory project of materials discovered at Czermno over the course of decades.

The small, purplish spindle whorl was unearthed by archaeologists in Czermno, Poland, in 1952. What the people who found it didn’t realize is that the biconical slate piece was inscribed, making it a unique find in the Polish archaeological record. It was Iwona Florkiewicz from the Institute of Archeology of the University of Rzeszów who discovered how precious this little piece really during an inventory project of materials discovered at Czermno over the course of decades.

Palaeographic research (on the form of writing) carried out by Dr. Adrian Jusupović, historian from the Institute of History PAS in Warsaw, shows that the inscription was made in the second half of the 12th century or in the 13th century.

The spindle whorl bears an inscription composed of 6 letters in Cyrillic, which can be transcribed as Hoten\’. It is a masculine name that means a lover, volunteer or master. It is also possible that the inscription was a toponym. In that case it should be associated with the name of a town or village. But researchers find this second possibility is less likely.

It is the only spindle whorl with a text inscription from this period ever discovered in Poland. It’s likely not of Polish origin, in fact. The slate itself is a non-native material. It is Volhynian slate, recognizable from its characteristic shades of pink to purple, found in the Ukraine. From the 11th century through the mid-13th, craftsmen in the nearby town of Owrucz produced inexpensive spindle whorls from the slate that were sold throughout the Kievan Rus and in what is now Poland. This trade came to an abrupt end in the 1240s when the invading Mongols destroyed the spindle whorl workshops.

While it’s possible the spindle was an import that was then inscribed in Poland, the lettering and indeed the inscription itself suggest it came to Poland with the inscription already done. Not only is it written in Cyrillic, but a number of inscribed spindle whorls have been found in the former territory of the Kievan Rus (Ukraine, Russia and Belarus), whereas this the first found in Poland.

As Czermno was a border town, it was yanked and forth between Poland and the Kievan Rus for centuries. The Kievans took it in the 10th century. Bolesław the Brave of Poland’s Piast dynasty took it back in 1018. After his death in 1025, Czermno’s fortunes shifted again and Yaroslav the Wise, Grand Prince of Rus, reconquered the town and region in 1031. There it stayed until the 14th century when Casimir III the Great reclaimed it for Poland. So at the time this spindle whorl was made, Czermno was firmly in the ambit of the Kievan Rus.

“We are not sure whether the spindle whorl was used for its original purpose – spinning – or had a secondary function as an amulet. The latter possibility should not be ruled out” – Florkiewicz believes. She adds that according to the researchers, similar inscriptions could be signs of ownership. There are known spindle whorls that bear the names of women and men. “It is also possible that in this case it is the name of the object’s maker” – she concludes.