Archaeologists have identified the bones of probable polo donkeys in the tomb of a Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.) noblewoman. Tang-era texts do describe the sport of lvju, or donkey polo, played by royalty and nobility, but this is the first archaeological evidence of it.

Archaeologists have identified the bones of probable polo donkeys in the tomb of a Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.) noblewoman. Tang-era texts do describe the sport of lvju, or donkey polo, played by royalty and nobility, but this is the first archaeological evidence of it.

The tomb was discovered in 2012 in Xi’an, ancient Chang’an, onetime capital of the Tang Dynasty. The brick structure has a vertical entrance, a corridor and a burial chamber with brick-lined floors. The contents had been looted in antiquity, but there were some artifacts found, including a lead stirrup and a stone epitaph. The tomb and murals of servants and musicians at a funerary feast indicate she was a member of the societal elite. The epitaph confirmed her status, identifying the tomb as that of the Lady Cui Shi, wife of Bao Gao, governor of two administrative regions in the late Tang Dynasty. The inscription notes she died October 6th, 878, when she was 59 years old, and was buried August 15th, 879.

Chang’an was located at the beginning of the Silk Road and donkeys were highly valued as pack animals to transport goods along the trade routes. Tang Dynasty texts refer to them being used in households and pack animals and in military and governmental transports. An edict of the period prohibited donkeys being killed or eaten. Commoners were known to ride them for transportation, but not the upper classes.

Polo is believed to have developed in Persia and spread east through the influence of the Parthian Empire (ca. 247 B.C. – 224 A.D.). Polo played on horseback was established as a prestigious sport in central China. At the Tang court it was valued as a proving ground for cavalry skills, but it was dangerous, even fatal to play. Lvju used sturdier, shorter, easier to handle donkeys and therefore appealed to women and older players.

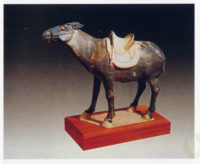

Only two pottery figurines of donkeys wearing saddles have been unearthed in Tang tombs in Xi’an. The discovery of skeletal remains of three donkeys among piles of animal bones in the corridor and on the coffin of Cui Shi’s tomb gave researchers the unique opportunity to analyze their bones and determine what they were used for in life and why they were buried in a noble woman’s tomb.

Only two pottery figurines of donkeys wearing saddles have been unearthed in Tang tombs in Xi’an. The discovery of skeletal remains of three donkeys among piles of animal bones in the corridor and on the coffin of Cui Shi’s tomb gave researchers the unique opportunity to analyze their bones and determine what they were used for in life and why they were buried in a noble woman’s tomb.

Dental analysis identified the different equid species in the mix. Their ages were determined by tooth eruption on the jaws and wear patterns. Measurements of metatarsals from three individuals determined their sizes. Stable isotope analysis was done on the metatarsals of two specimens. Micro-CT scans were done of three humeri from two donkeys to determine the biomechanical stress they were subjected to, a marker of whether these donkeys were pack animals in life. Radiocarbon dating found the donkeys’ date range coincides with the one in the epitaph, 856-898 A.D.

Dental analysis identified the different equid species in the mix. Their ages were determined by tooth eruption on the jaws and wear patterns. Measurements of metatarsals from three individuals determined their sizes. Stable isotope analysis was done on the metatarsals of two specimens. Micro-CT scans were done of three humeri from two donkeys to determine the biomechanical stress they were subjected to, a marker of whether these donkeys were pack animals in life. Radiocarbon dating found the donkeys’ date range coincides with the one in the epitaph, 856-898 A.D.

One hint to why they were in Cui’s tomb, [Washington University in St. Louis anthropologist Fiona Marshall] says, may lie in the identity of her husband, Bao Gao. Ancient texts reveal that the polo-obsessed Emperor Xizong promoted Bao to the rank of general because of his skills on the polo fields. Polo was wildly popular during the Tang dynasty—for both women and men—but it was also dangerous; riders thrown from their horses were frequently injured or killed. If a woman like Cui wanted to join a game, then riding a donkey—slower, steadier, and lower to the ground—might have been a safer alternative.

When the researchers, led by archaeologist Songmei Hu of the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, analyzed the size of the donkey bones in Cui’s tomb, they found that they were too small to have been good pack animals. Computerized tomography scans of the leg bones revealed patterns of stress similar to an animal that ran and turned frequently, rather than one that slowly trudged in a single direction. Taken together, the evidence suggests Cui played polo astride a donkey, the researchers report today in Antiquity. The noblewoman’s donkeys may have been ritually sacrificed when she died to allow Cui to continue to play in the afterlife.

“There’s no smoking gun … [but] there’s really no other explanation that makes sense,” Marshall says, adding that the finding suggests Tang dynasty donkeys were held in higher regard than believed.

Read the full study published in Antiquity here.