The remains of a ram skull have been found inside a clay funerary mask of a 2,100-year-old human head from Siberia’s Bronze Age Tagar culture. A Scythian people who inhabited southwestern Siberia between then 8th and 2nd century B.C., the Tagar farmed and raised livestock. They are also known for their fine bronze metalwork and left an indelible mark on the landscape with their large burial mounds. More than a thousand Tagar barrows have been excavated in the Minusinsk Hollow, now in the Republic of Khakassia and in the eastern part of the Kemerovo Oblast.

The remains of a ram skull have been found inside a clay funerary mask of a 2,100-year-old human head from Siberia’s Bronze Age Tagar culture. A Scythian people who inhabited southwestern Siberia between then 8th and 2nd century B.C., the Tagar farmed and raised livestock. They are also known for their fine bronze metalwork and left an indelible mark on the landscape with their large burial mounds. More than a thousand Tagar barrows have been excavated in the Minusinsk Hollow, now in the Republic of Khakassia and in the eastern part of the Kemerovo Oblast.

Low in height and edged with vertical stone slabs, the mounds started out as single burials for the societal elite. They contained one or two individuals in chambered graves. Come the 5th century B.C., the funerary tradition shifted. The mounds grew much larger, up to 100 feet high and exceeding 130 feet in diameter. Inside was a large single pit containing as many as 100 bodies.

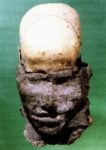

The clay heads belong to the final stage of the Tagar culture, the Tesinsky stage (2nd-1st century B.C.). In Tesinsky crypts, believed to be large family tombs, the remains were treated with an attempt at mummification. Archaeologist Dr Elga Vadetskaya believes they were buried in two stages. First their bodies were placed in a stone coffin and buried in a shallow grave or under a pile of rocks. After a few years, the skeleton and any surviving soft tissues (mainly tendons and spinal cord) were wrapped with grass, leather and bark to make a sort of human-remain doll.

The clay heads belong to the final stage of the Tagar culture, the Tesinsky stage (2nd-1st century B.C.). In Tesinsky crypts, believed to be large family tombs, the remains were treated with an attempt at mummification. Archaeologist Dr Elga Vadetskaya believes they were buried in two stages. First their bodies were placed in a stone coffin and buried in a shallow grave or under a pile of rocks. After a few years, the skeleton and any surviving soft tissues (mainly tendons and spinal cord) were wrapped with grass, leather and bark to make a sort of human-remain doll.

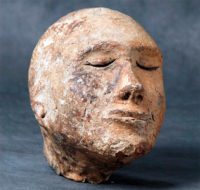

The skull was then fashioned into a clay head. The nose, eye sockets and mouth were filled with clay. A layer of clay was applied to the whole skull and the facial features sculpted with no care to replicating the real facial features of the deceased. The clay was coated in gypsum and painted. The paint patterns on the faces are believed to have been marks identifying family or clan membership.

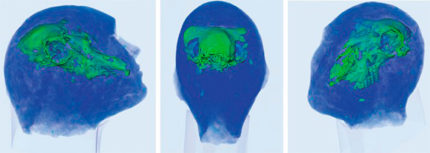

The clay face of a young man was unearthed in 1968 from a Tagar tumulus in the Shestakovsky burial ground in Khakassia. It was X-rayed at the time, but the technology could only convey that the presence of skull bones and a hollow space smaller than the interior of a human skull. Researchers decided not to open the clay exterior as it would be damaged beyond the repair.

That head was recently given new X-rays using fluoroscopy imaging and this time the results were unambiguous: inside the human-featured head was the skull of a sheep. This is the first time a non-human skull has been found inside a Tagar clay funerary head. Researcher Natalya Polosmak has two hypotheses explaining this practice.

That head was recently given new X-rays using fluoroscopy imaging and this time the results were unambiguous: inside the human-featured head was the skull of a sheep. This is the first time a non-human skull has been found inside a Tagar clay funerary head. Researcher Natalya Polosmak has two hypotheses explaining this practice.

She believes the Tagar people ‘may have buried in this extraordinary manner a man whose body had not been found’.

She surmises that the man ‘could have got lost in the taiga, drowned, or disappeared in alien lands’.

For this reason he was ‘replaced with his double – the animal in which his soul was embodied’ and in this was sent to the afterlife alongside the remains of his fellow humans.

‘This must have been the only way to ensure the after-death life of a person who had not returned home.

‘Archaeologists know a number of such burials, referred to as cenotaphs, which have no human remains but may contain a symbolic replacement. As the latter, an animal could have been used.’

Her other theory for the ‘false burial’ is that it may have been done to give the man ‘a chance to have a fresh start, a new life in a new status.

‘Instead of a living man whose death was staged for some reason, an animal – a sheep in human disguise – was offered.’

Dr. Vadetskaya posits the mummy “dolls” and clay heads were returned to the family who kept them until a second funeral was held. The evidence for this is that the gypsum and paint of some of the clay heads has been repaired, sometimes repeatedly. This had to have been a precarious wait. The bodies and heads ran the risk of decomposing or being too damaged to rebury, in which case the families would have to recreate at least the clay heads.

That is what Vadetskaya thinks happened in this case; that the families used a ram’s skull as a placeholder for the lost human skull so that the second funeral could still take place.