An excavation of the colonial site of Historic St. Mary’s City in Maryland has uncovered a rare piece from a 17th-century suit of armor. The concave metal plate is a tasset, a piece attached to the base of the breastplate to protect the thigh. Still caked with soil and corrosion materials, the plate was identified when an X-ray revealed its rivets forming the shape of three hearts.

An excavation of the colonial site of Historic St. Mary’s City in Maryland has uncovered a rare piece from a 17th-century suit of armor. The concave metal plate is a tasset, a piece attached to the base of the breastplate to protect the thigh. Still caked with soil and corrosion materials, the plate was identified when an X-ray revealed its rivets forming the shape of three hearts.

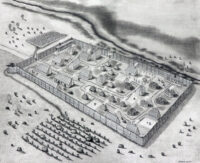

St. Mary’s City was the fourth English colony in America after Jamestown, Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colony (in that order). Founded in March 1634 on land acquired from the local Yaocomico people by the newly-arrived English settlers, it was the first capital of the colony of Maryland for 60 years until it was moved to Annapolis in 1694. St. Mary’s was abandoned after it was eclipsed by Annapolis and never built over, making it an undisturbed archaeological site.

Today Historic St. Mary’s City (HSMC) is an outdoor living history museum with reconstructed colonial-era buildings, a working farm, a replica of one of the two ships that brought the colonists across the Atlantic and costumed reenactors staffing the exhibits. HSMC also has an archaeological field school which conducts excavations of the site and trains archaeology students. One of the goals of the archaeological explorations over the past five decades has been to find evidence of the original fortified village Documentation from the 17th century was vague on the geographic details, and all mentions of the first fort disappear from the historical record in 1642.

Today Historic St. Mary’s City (HSMC) is an outdoor living history museum with reconstructed colonial-era buildings, a working farm, a replica of one of the two ships that brought the colonists across the Atlantic and costumed reenactors staffing the exhibits. HSMC also has an archaeological field school which conducts excavations of the site and trains archaeology students. One of the goals of the archaeological explorations over the past five decades has been to find evidence of the original fortified village Documentation from the 17th century was vague on the geographic details, and all mentions of the first fort disappear from the historical record in 1642.

After a geophysical survey found indications of a palisade, an excavation in 2021 unearthed postholes, the outlines of buildings, coins and artifacts from the 1620s and 1630s. The excavation of the original fort has continued, and late last year a large building with an attached cellar was found. The building wasn’t a home, and artifacts found there — musket parts, lead shot, trade beads — suggest it may have been used as a storehouse. The tasset was discovered in the cellar.

After a geophysical survey found indications of a palisade, an excavation in 2021 unearthed postholes, the outlines of buildings, coins and artifacts from the 1620s and 1630s. The excavation of the original fort has continued, and late last year a large building with an attached cellar was found. The building wasn’t a home, and artifacts found there — musket parts, lead shot, trade beads — suggest it may have been used as a storehouse. The tasset was discovered in the cellar.

The colonists brought many things on their journey: food, tools, weapons, armor. As they experienced life in southern Maryland, they adjusted. Archaeologists think tassets may have been items the colonists found were no longer useful.

Finding the tasset “tells us there was body armor here in the colony,” Parno said. “It also tells us [the colonists] were adapting to the environment. The tassets may have been something that were discarded because they were deemed unnecessary.”

“They’re heavy,” he said. “It’s a hot, humid environment. So you get rid of the tassets. … You keep your breastplate, though, because that’s protecting your core.”