The city of Le Mans in northwestern France is probably best known for the 24-hour endurance sports car race that bears its name, but it has the far greater distinction of having the best preserved late Roman defensive walls surviving in France and in the top three best preserved Roman walls in the former Empire. The only other comparable ones are the walls of Rome itself and of Constantine’s second Rome (ie, Istanbul).

The city of Le Mans in northwestern France is probably best known for the 24-hour endurance sports car race that bears its name, but it has the far greater distinction of having the best preserved late Roman defensive walls surviving in France and in the top three best preserved Roman walls in the former Empire. The only other comparable ones are the walls of Rome itself and of Constantine’s second Rome (ie, Istanbul).

The Roman walls of Le Mans cover an area of 8.5 hectares. There were 40 towers originally; today 19 of them are preserved, looming 50 feet high. The walls between them were built in a typical Roman technique: parallel brick facings with mortar between them. They average more than 30 feet high and are 15 feet thick at the base. To build these monumental defenses, workers used 400,000 bricks, 140,000 tons of rubble, 60,000 tons of mortar and 50,000 square feet of reused foundation blocks.

The Roman walls of Le Mans cover an area of 8.5 hectares. There were 40 towers originally; today 19 of them are preserved, looming 50 feet high. The walls between them were built in a typical Roman technique: parallel brick facings with mortar between them. They average more than 30 feet high and are 15 feet thick at the base. To build these monumental defenses, workers used 400,000 bricks, 140,000 tons of rubble, 60,000 tons of mortar and 50,000 square feet of reused foundation blocks.

The masonry and brickwork are uniquely decorated. Contrasting colors of terracotta bricks, pink mortar, red sandstone, light sandstone, white limestone were arranged to create chevrons, columns, X-shapes, flowers and more. Researchers have identified 14 different motifs. Roman enclosures elsewhere do not have this feature, while other ancient structures in the Le Mans area do, so it seems this was a local aesthetic carried forward through this monumental undertaking.

The masonry and brickwork are uniquely decorated. Contrasting colors of terracotta bricks, pink mortar, red sandstone, light sandstone, white limestone were arranged to create chevrons, columns, X-shapes, flowers and more. Researchers have identified 14 different motifs. Roman enclosures elsewhere do not have this feature, while other ancient structures in the Le Mans area do, so it seems this was a local aesthetic carried forward through this monumental undertaking.

Historians have long believed that the walls were built around 280 A.D. in reaction to the Crisis of the Third Century. Before the Crisis, 25 Gallo-Roman cities had fortified defensive walls. More than 80 Gallo-Roman towns built new walls in the late third and early fourth centuries. They are easily distinguished from walls built in earlier times because they are much thicker, higher, have more towers and were made with recycled construction materials. The foundations of Le Mans’ walls were built with the stone from the city’s public baths, deliberately demolished to provide construction materials for the new fortifications.

Historians have long believed that the walls were built around 280 A.D. in reaction to the Crisis of the Third Century. Before the Crisis, 25 Gallo-Roman cities had fortified defensive walls. More than 80 Gallo-Roman towns built new walls in the late third and early fourth centuries. They are easily distinguished from walls built in earlier times because they are much thicker, higher, have more towers and were made with recycled construction materials. The foundations of Le Mans’ walls were built with the stone from the city’s public baths, deliberately demolished to provide construction materials for the new fortifications.

In 2017, a new in-depth exploration of the walls was undertaken by city archaeologists and historians. Samples were taken from the bricks and mortar of the walls in the attempt to confirm its date. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), Carbon-14 analysis and archaeomagnetic dating of the samples all returned unexpected results. The wall was built in the 4th century, not the third, between 320 and 360 A.D. That means the massive fortifications were not built under pressure from barbarian raids and ineffectual imperial management, but rather during a period of comparative stability in the Late Empire.

In 2017, a new in-depth exploration of the walls was undertaken by city archaeologists and historians. Samples were taken from the bricks and mortar of the walls in the attempt to confirm its date. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), Carbon-14 analysis and archaeomagnetic dating of the samples all returned unexpected results. The wall was built in the 4th century, not the third, between 320 and 360 A.D. That means the massive fortifications were not built under pressure from barbarian raids and ineffectual imperial management, but rather during a period of comparative stability in the Late Empire.

The samples were only taken from one section of the wall. Archaeologists plan to analyze other sections as well to discover whether the fortifications were all built so late, or if some parts were begun in the third century and construction took place over many decades.

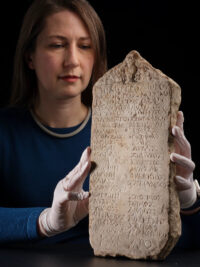

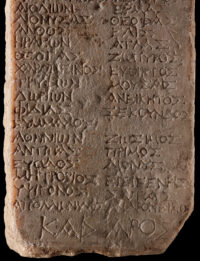

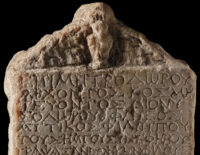

The Jean-Claude-Boulard-Carré Plantagenêt Museum in Le Mans is hosting the first major exhibition dedicated to the city’s exceptional Roman walls. The exhibition explores the wall’s meaning beyond its military application, its construction materials and methods, how it was altered between the 5th and 18th century, and its rediscovery in the 19th century.

The Jean-Claude-Boulard-Carré Plantagenêt Museum in Le Mans is hosting the first major exhibition dedicated to the city’s exceptional Roman walls. The exhibition explores the wall’s meaning beyond its military application, its construction materials and methods, how it was altered between the 5th and 18th century, and its rediscovery in the 19th century.