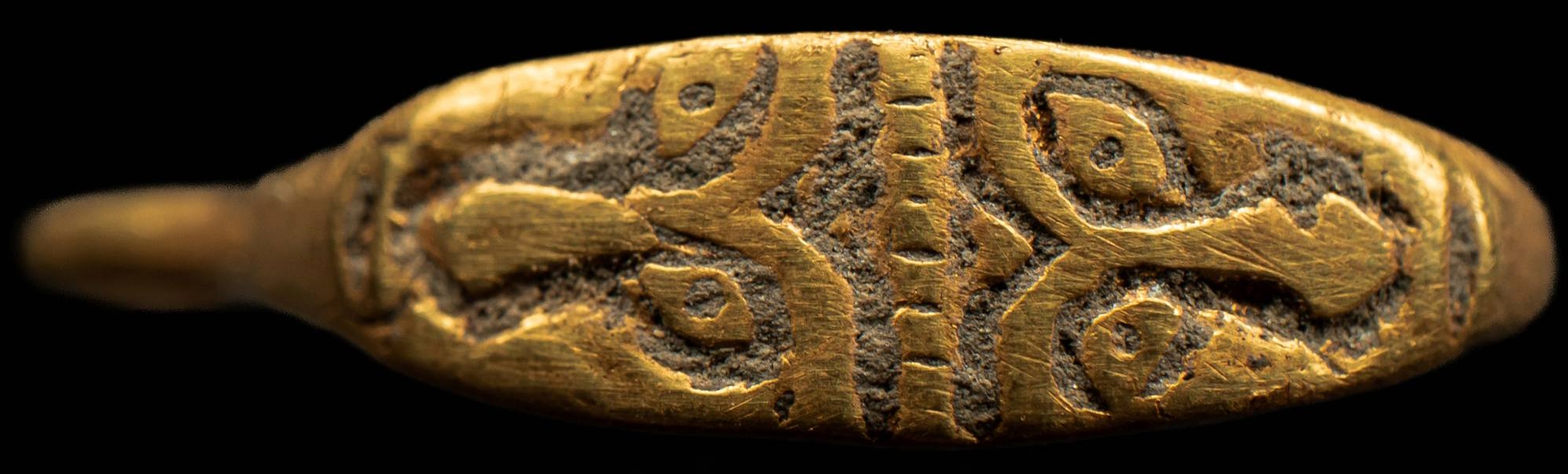

A gold ring from the 11th or 12th century with an unusual two-faced design has been discovered at Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków. The top of the ring is widened and flattened. It is engraved with two anthropomorphic figures, faces looking away from each other. This is the only example ever discovered of an early medieval Polish ring decorated with figural representations, let alone human faces. The few gold rings from the period that have been found in Poland are either undecorated or ornamented with simple geometric designs.

A gold ring from the 11th or 12th century with an unusual two-faced design has been discovered at Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków. The top of the ring is widened and flattened. It is engraved with two anthropomorphic figures, faces looking away from each other. This is the only example ever discovered of an early medieval Polish ring decorated with figural representations, let alone human faces. The few gold rings from the period that have been found in Poland are either undecorated or ornamented with simple geometric designs.

The ring is 1.5mm thick, 4mm in diameter with a circumference of 57mm. The bottom of the band is broken, but there does not appear to have been a great deal of gold lost. The overall shape and style of the ring is typical of this area of Poland, so it was likely produced locally for an elite member of the Piast dynasty court.

The ring is 1.5mm thick, 4mm in diameter with a circumference of 57mm. The bottom of the band is broken, but there does not appear to have been a great deal of gold lost. The overall shape and style of the ring is typical of this area of Poland, so it was likely produced locally for an elite member of the Piast dynasty court.

The royal castle on Wawel Hill towers over the historic center of Kraków. The earliest royal residence at the site was built by Mieszko I (r. ca. 960–992), the first king of Poland. He converted to Christianity in 966 and eight years after his death the first cathedral in Poland was built next to the royal castle on Wawel Hill. Polish kings would be crowned and buried there for centuries.

The early medieval castle was greatly expanded and modernized into a splendid Renaissance palace by the Jagiellonian dynasty kings (Alexander I, Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus) of the 16th century. The court was moved from Kraków to Warsaw in 1609 and Wawel Castle fell into a slow decline that was violently sped up when it was sacked by Swedish troops during the Deluge campaigns (1648-1667). Come the partitions of Poland in the late 18th century, the devastated castle was repurposed as an army barracks for Austrian troops. Poland reclaimed it with its own independence in 1918 when it served both as residence for the head of state and as a museum.

The gold ring was discovered during an archaeological excavation under the Danish Tower, a residential tower on the east wing of the castle built in the late 14th century, but the ring predates construction of the tower. It was in the archaeological layer on top of the remains of an older stone structure that may have been a defensive rampart.

The ring will now undergo metal analysis that may provide more data about the composition and origin of the gold. When the scientific research is complete, the ring will go on display.