The second of a 1300-year-old pair of skis has been discovered in the Mount Digervarden ice patch in southern Norway. Together they form the best-preserved pair of ancient skis in the world, and the only ones with surviving bindings that provide essential information on how the skis were worn.

A team of glacier archaeologists discovered the first of the pair in the Digervarden ice patch in 2014. Complete with surviving birch bindings, it  was an exceptional find, one of only two pre-Viking skis ever found with bindings. The team has kept an eye on the site ever since, monitoring the melting ice via satellite in case the receding ice might reveal the ski’s match.

was an exceptional find, one of only two pre-Viking skis ever found with bindings. The team has kept an eye on the site ever since, monitoring the melting ice via satellite in case the receding ice might reveal the ski’s match.

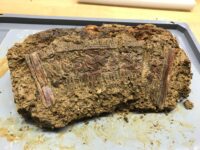

This year they saw the ice had retreated significantly, so three weeks ago a team did a field check and discovered a second ski trapped in the ice 16 feet away from where the first ski was found. It was too firmly embedded in the ice to be removed on the spot, so a large, well-equipped team returned six days later to liberate the historic ski. After shoveling away snow and chipping through the thick ice with an axe, team members were able to uncover the entire ski. A little lukewarm water loosened it all the way and the ski was retrieved.

It was found upside down in the ice. When archaeologists turned it face-up, they saw that it too had surviving binding, and it was the exact same type of binding on the ski found in 2014. This was confirmation that they were a matched set.

It was found upside down in the ice. When archaeologists turned it face-up, they saw that it too had surviving binding, and it was the exact same type of binding on the ski found in 2014. This was confirmation that they were a matched set.

They are not identical, however. The newly-found ski is in far better condition because it was 15 feet deeper down in the ice than the previous find. At 6’2″ long and seven inches wide, it is seven inches longer and .8 inches wider than the first ski. This is likely due to the 2014 ski having shrunk and warped from being more exposed than its partner.

There are other differences as well, which is to be expected with handmade objects that experienced all kinds of wear and tear in the mountains of Iron Age Finland.

There are other differences as well, which is to be expected with handmade objects that experienced all kinds of wear and tear in the mountains of Iron Age Finland.

Three twisted birch bindings, a leather strap and a wooden plug go through the hole in the foothold of the new ski. The ski found in 2014 only had one twisted birch binding and a leather strap through the hole. Both skis have a hole through the tip. There are subtle differences in the carvings at the front of the skis. The back end of the new ski is pointed, while the back end of 2014 ski is straight.

The foothold of the new ski shows repairs, so it was well used. A part of the back end of the ski is missing. The missing piece is presumably still inside the ice. Whether it broke when lost or while inside the ice may be possible to say at a later stage based on a careful study of the edge of the break.

Part of the leather strap of the heel binding of the new ski had come off but it lay on the ground close by. Both skis are missing the upper part of the toe binding of twisted birch. We found pieces of twisted birch close to the new ski and this may belong to the binding. We cannot to say for sure if the binding of twisted birch broke before the skis were left behind, or whether the ice caused it.

This video captures the excavation and recovery of the ski: