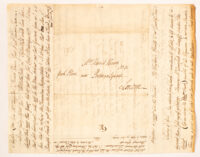

A lost letter by Dr. Samuel Johnson, illustrious author, literary critic and compiler of the seminal Dictionary of the English Language, has been discovered in a cupboard in a country house in Gloucestershire. The letter was known from his correspondence catalogue, but it was listed as “present location unknown” for decades.

A lost letter by Dr. Samuel Johnson, illustrious author, literary critic and compiler of the seminal Dictionary of the English Language, has been discovered in a cupboard in a country house in Gloucestershire. The letter was known from his correspondence catalogue, but it was listed as “present location unknown” for decades.

It was discovered by a Chorley’s auction expert who had been called in by the homeowner for a routine valuation of some books and rugs. In a cupboard in the library, he found some historic records of the household expenditures, diaries and a volume of more than 100 letters that the family didn’t even realize was there. Manuscript specialists examined the volume, and found the lost letter by Dr. Johnson.

The letter was written on July 24, 1783, a year and a half before Johnson’s death.

He penned the missing letter to a Sophia Thrale (1771-1824), the daughter of Hester Lynch Thrale (1741-1821, later Mrs Piozzi), a British author and patron of the arts, who Johnson corresponded with so regularly and in so much detail, that her letters later became historically important published resources into 18th century society and the great mind of Dr Johnson. The two became acquainted when Hester, who came from one of the most illustrious Welsh land-owning dynasties; the Salusbury family, married the brewer Henry Thrale in 1763 and moved to London. It was at this time that she met leading literary figures, such as Dr Johnson, who became close friends with her and her children.

The current letter to a twelve-year-old Sophia Thrale, the sixth daughter of Hester Lynch Thrale, is the only known letter between them to survive, although there are several references to others in Johnson’s published letters. In the letter the elderly Johnson chides Sophia for not thinking of herself as his favourite; ‘my favour will, I’m afraid never be worth much, but its value more or less, you are never likely to lose it.’ He also praised her arithmetical ability; ‘Never think, my Sweet, that you have arithmetick enough, when you have exhausted your master, buy books, nothing amuses more harmlessly than computation’, and pointing her to a ‘curious calculation’ relating to the capacity of Noah’s Ark in Wilkins’s Real Character, he says; ‘an essay towards a real character and a philosophical language’ (1668 by John Wilkins).

Johnson ended his correspondence with the Thrales shortly after he wrote this letter. The widowed Hester remarried a broke Italian music tutor of whom the esteemed lexicographer did not approve, but they made up before his death in December 1784. Hester Thrale published a book based on their correspondence in 1786.

Johnson ended his correspondence with the Thrales shortly after he wrote this letter. The widowed Hester remarried a broke Italian music tutor of whom the esteemed lexicographer did not approve, but they made up before his death in December 1784. Hester Thrale published a book based on their correspondence in 1786.

Sophia would go on to marry the banker Merrick Hoare, and 30 letters written between mother and daughter after the marriage were also discovered at the Gloucestershire estate.  Another volume, Laws of London, signed by Robert Hoare (also a banker and the former Mayor of London) was found in the same cupboard as the volume of letters. This suggests Dr. Johnson’s long-lost letter made its way through the Hoare family to the Gloucestershire family, although what the specific connection was is unknown.

Another volume, Laws of London, signed by Robert Hoare (also a banker and the former Mayor of London) was found in the same cupboard as the volume of letters. This suggests Dr. Johnson’s long-lost letter made its way through the Hoare family to the Gloucestershire family, although what the specific connection was is unknown.

The letter from Samuel Johnson to Sophia Thrale will be going under the hammer at Chorley’s September 19th The Library: Printed Books & Manuscripts auction. The pre-sale estimate is £8,000-£12,000 ($10,000-$15,000).