Archaeologists have unearthed a Neolithic dragon figure made of mussel shells at the Caitaopo Site in Chifeng, in north China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It was meticulously crafted by the Neolithic Hongshan Culture (4700-2900 B.C.) which is known for producing some of the earliest examples of carved jade, including a C-shaped jade dragon that has become emblematic of the Hongshan Culture.

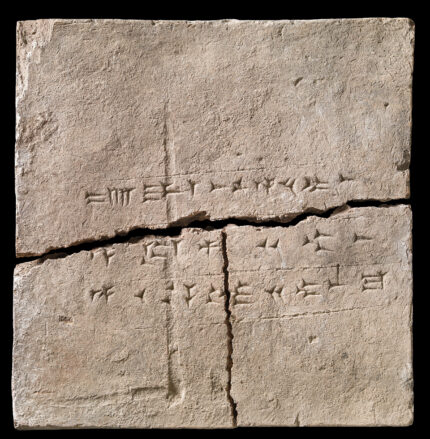

Found in the southwest corner of a house at the Caitaopo Site, the piece is eight inches wide and combines several different shells arranged together seamlessly to form the entire body of the dragon from head to tail. Also found in the same archaeological layer of the dwelling were pieces of cylindrical grey pottery, one with a line pattern decoration and another with a lettering pattern. The pottery dates the house and the dragon to the early period of the Hongshan Culture, making it much older than the iconic jade dragon which was previously believed to be the oldest known representation of a dragon on the archaeological record.

It is very different from the stylized, abstract representation of the C-shaped design. It is more realistic in its minute details, with everything from the teeth to rhombic scales on the tail carved into the shells’ surfaces. The mouth is short and wide. A pierced circular hole represents the eye under the dragon’s forehead. There are four more circular holes where the tail and lower body meet. Archaeologists believe the parts may have been connected by a string threaded through the holes.

These dragons, while artistically different, also differ in the archaeological contexts of their discoveries. The jade artifacts previously unearthed, belonging to the Hongshan Culture, were predominantly found in locations that suggest their association with high-grade ritualistic practices. These places were likely of significant importance, possibly serving as ritual buildings or sacred sites.

In contrast, the mussel shell dragon, given its unique composition and the location of its discovery, seems to hint at the spiritual beliefs of people residing in lower-grade settlements. This distinction underscores the cultural diversity and societal stratifications of the Hongshan Culture, presenting a richer tapestry of their way of life, beliefs, and rituals.

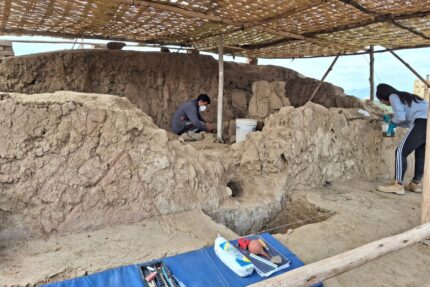

The mussel shell dragon has been extracted from the site in a soil block so it can be micro-excavated in laboratory conditions by expert conservators.