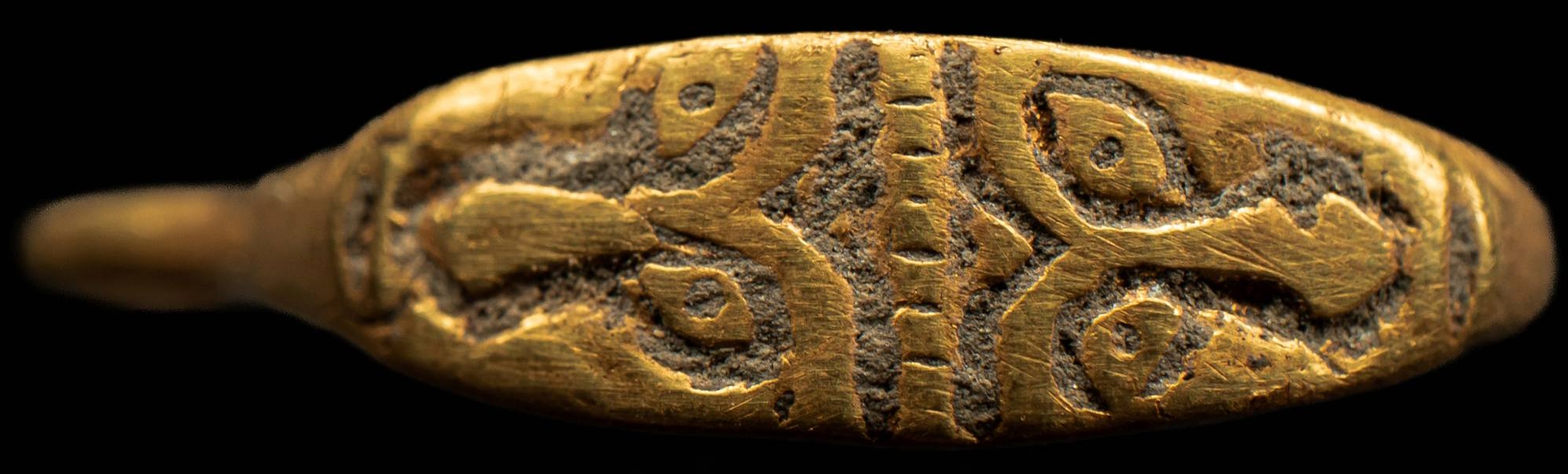

A tin turtle dove badge from the Middle Ages has been discovered during renovations of the 600-year-old Gdańsk port crane. The love token features a turtle dove perched on a banner inscribed “Amor Vincit Omnia,” meaning “love conquers all.” The badge originally had two loops on the back, now broken off, from which it would have been threaded on a chain or on a pin. These types of tokens were popular in the 14th and 15th centuries, a fashion imported from the west as similar pieces have been found in the Netherlands and Britain.

A tin turtle dove badge from the Middle Ages has been discovered during renovations of the 600-year-old Gdańsk port crane. The love token features a turtle dove perched on a banner inscribed “Amor Vincit Omnia,” meaning “love conquers all.” The badge originally had two loops on the back, now broken off, from which it would have been threaded on a chain or on a pin. These types of tokens were popular in the 14th and 15th centuries, a fashion imported from the west as similar pieces have been found in the Netherlands and Britain.

The love token was unearthed during work on the foundations of the Gdańsk Crane, a marvel of medieval technology and of historic preservation. The oldest surviving port crane in Europe, it was built between 1442 and 1444. The crane is a wooden structure between two three-story brick towers over the Motława river and was the largest water gate in Gdańsk. It was heavily defended, with cannon on the ground floor and openings in the upper stories for small arms to fire through.

The love token was unearthed during work on the foundations of the Gdańsk Crane, a marvel of medieval technology and of historic preservation. The oldest surviving port crane in Europe, it was built between 1442 and 1444. The crane is a wooden structure between two three-story brick towers over the Motława river and was the largest water gate in Gdańsk. It was heavily defended, with cannon on the ground floor and openings in the upper stories for small arms to fire through.

The crane was used to raise heavy loads (cargo, masts for ship construction) to and from the water. It was powered by a mechanism of four human-powered treadmill wheels more than 20 feet in diameter on a common shaft. When all four wheels were employed, it could hoist cargo weighing up to two tons more than 80 feet high. Each treadwheel was operated by four men walking like hamsters. While its importance to trade and shipbuilding was already in decline in the 18th century, it was still being used in 1944. Much of it burned in 1945 and was reconstructed in the late 1950s and 1960s.

The crane was used to raise heavy loads (cargo, masts for ship construction) to and from the water. It was powered by a mechanism of four human-powered treadmill wheels more than 20 feet in diameter on a common shaft. When all four wheels were employed, it could hoist cargo weighing up to two tons more than 80 feet high. Each treadwheel was operated by four men walking like hamsters. While its importance to trade and shipbuilding was already in decline in the 18th century, it was still being used in 1944. Much of it burned in 1945 and was reconstructed in the late 1950s and 1960s.

The crane is part of the National Maritime Museum in Gdańsk today, but has been closed to visitors since 2020 while the building undergoes the largest renovation project since its reconstruction after it took heavy damage during World War II. This time the focus was on historical accuracy and conserving the surviving original elements like the 1688 sundial on the southern tower. The monument, an icon of the city, has a newly clean brick façade and a new roof covered in ceramic tiles imported from Italy. The wooden crane housing looks completely different. Before the renovation it was black; now it has been repainted a warm brown that matches its appearance in depictions from centuries ago.

The crane is part of the National Maritime Museum in Gdańsk today, but has been closed to visitors since 2020 while the building undergoes the largest renovation project since its reconstruction after it took heavy damage during World War II. This time the focus was on historical accuracy and conserving the surviving original elements like the 1688 sundial on the southern tower. The monument, an icon of the city, has a newly clean brick façade and a new roof covered in ceramic tiles imported from Italy. The wooden crane housing looks completely different. Before the renovation it was black; now it has been repainted a warm brown that matches its appearance in depictions from centuries ago.

The interior has also been restored and updated with six rooms on the three stories of the Crane that will display Gdańsk’s mercantile history. Visitors will learn about the navigation of the port, how business was transacted by merchants and customs agents, shipbuilding techniques, the home life and downtime of Gdańsk’s residents. New recreations of historic spaces — a merchant’s office, a tavern and a bedroom in a burgher’s house — will give visitors a look at how people lived and worked in 17th century Gdańsk. And get this, the rooms will all have holographic guides, 3D moving holograms of a customs official, an innkeeper and a fictional composite of a merchant and shipowner named Hans Kross. How Star Trek is that? “Please state the nature of your mercantile emergency.”

The interior has also been restored and updated with six rooms on the three stories of the Crane that will display Gdańsk’s mercantile history. Visitors will learn about the navigation of the port, how business was transacted by merchants and customs agents, shipbuilding techniques, the home life and downtime of Gdańsk’s residents. New recreations of historic spaces — a merchant’s office, a tavern and a bedroom in a burgher’s house — will give visitors a look at how people lived and worked in 17th century Gdańsk. And get this, the rooms will all have holographic guides, 3D moving holograms of a customs official, an innkeeper and a fictional composite of a merchant and shipowner named Hans Kross. How Star Trek is that? “Please state the nature of your mercantile emergency.”

The Gdańsk Crane is scheduled to reopen April 30th, 2024. The turtle dove love token, currently undergoing cleaning and conservation, will be on display in the renovated museum space when it opens.