Woven textiles discovered at the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in central Turkey that were thought to be linen have been identified as bast fiber harvested from local oak trees. Unearthed in the first excavations at the site between 1962 and 1965, the textiles date to between 6700 and 6500 B.C., making them the oldest preserved woven fabrics in the world.

Woven textiles discovered at the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in central Turkey that were thought to be linen have been identified as bast fiber harvested from local oak trees. Unearthed in the first excavations at the site between 1962 and 1965, the textiles date to between 6700 and 6500 B.C., making them the oldest preserved woven fabrics in the world.

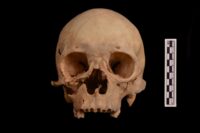

Today Çatalhöyük is famous for its unique construction — there are 18 successive archaeological layers extending down 70 feet of tightly clustered domestic dwellings built between 7100 and 5600 B.C. but no known public buildings — which straddles the transition between mobile hunter-gatherer communities and settled farming communities. The large site (13 hectares) is rich in art and artifacts, including wall paintings, ceramics and figurines. Organic objects like cords, baskets, mats and textiles have been found primarily in funerary bundles, used to wrap the tightly flexed bodies before burial under the floors of the habitation structures.

Archaeologists and experts who examined the textile finds in the 1960s thought they were made of either wool or linen. James Mellaart, the archaeologist who first excavated Çatalhöyük (he was later booted out of Turkey under suspicion of involvement with the illicit trade in antiquities and after his death was discovered to have been a full-on forger of “ancient” art as well) thought it was wool because the remains of sheep and rams had been found at the site. Researchers in 1988 concluded the textiles were plant-based, coming down on the flax side of the debate.

If it was linen, however, it could not have been locally produced. Only a dozen flax seeds have ever been found at Çatalhöyük, and only in layers from the early phase of Neolithic occupation whereas the textiles were found in layers from the middle phase of Çatalhöyük’s Neolithic occupation. Nor is there any evidence that flax or linen was imported to the site.

Excavations resumed again in 1993 and since then, additional textile finds have been made. The new discoveries spurred a reexamination of the old ones. Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) archaeological textile specialist Bender Jørgensen teamed up with University of Bern fiber specialist Antoinette Rast-Eicher, visiting the excavation in person to examine the new finds and looking with fresh new eyes (and technology) upon the textiles recovered in 1960s.

Excavations resumed again in 1993 and since then, additional textile finds have been made. The new discoveries spurred a reexamination of the old ones. Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) archaeological textile specialist Bender Jørgensen teamed up with University of Bern fiber specialist Antoinette Rast-Eicher, visiting the excavation in person to examine the new finds and looking with fresh new eyes (and technology) upon the textiles recovered in 1960s.

“In the past, researchers largely neglected the possibility that the fabric fibers could be anything other than wool or linen, but lately another material has received more attention,” Bender Jørgensen says.

People in Çatalhöyük used assorted varieties of exactly this material.

“Bast fibers were used for thousands of years to make rope, thread, and in turn also yarn and cloth,” says Bender Jørgensen.

A fiber sample from a basket turned out to be made of grass, but several of the textiles are clearly made of bast fiber from oak trees. […]

Bast fiber is found between the bark and the wood in trees such as willow, oak or linden. The people from Catalhöyük used oak bark, and thus fashioned their clothes from the bark of trees that they found in their surroundings. They also used oak timber as a building material for their homes, and people undoubtedly harvested the bast fibers when trees were felled.

The study has been published in the journal Antiquity.