Archaeologists from National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan have unearthed a Neolithic snake-shaped pottery handle. Radiocarbon dating found it is 4,000 years old. Crafted in the shape of a cobra with its upper body raised and hood flattened ready to strike, it was discovered during a 2023 excavation of a sand dune on the northwest coast of Taiwan in the Guanyin District of Taoyuan City. The site was a major center of stone tool manufacturing during the Neolithic era.

Archaeologists from National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan have unearthed a Neolithic snake-shaped pottery handle. Radiocarbon dating found it is 4,000 years old. Crafted in the shape of a cobra with its upper body raised and hood flattened ready to strike, it was discovered during a 2023 excavation of a sand dune on the northwest coast of Taiwan in the Guanyin District of Taoyuan City. The site was a major center of stone tool manufacturing during the Neolithic era.

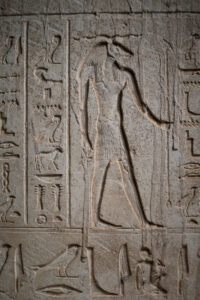

Snakes have symbolic significance in many religions around the world, including in East Asian cultures. They can represent healing, as on the caduceus of Asclepius, god of medicine, metamorphosis and rebirth due their ability to shed their skins, the circle of life, as in the ouroboros (serpent biting its tail) of ancient Egypt, as intermediaries between heaven, earth and the underworld, as in the Aztec feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl and Apollo’s python who transmitted prophecy from the underworld to earth.

“Snakes are often regarded as symbolic animals in religion, mythology and literature, and are considered to be the bridge between heaven and man,” [Hung-Lin Chiu, associate professor of the Institute of Anthropology at Tsing Hua] said.

Given their ability to shed their skin, ancient societies in the region associated these animals with the cycle of life and death, and considered them to be symbols of creation and transition.

The snake-shaped pottery handle may have come from a sacrificial vessel for shamans in ancient tribal societies to perform rituals, according to the researchers.

“This reflects that ancient societies incorporated animal images into ritual sacrificial vessels to demonstrate their beliefs and cognitive systems,” Chiu said.