A new study of the skeletal remains of two women discovered at the Middle Neolithic (4250-3600 B.C.) site of Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux in southern France has revealed they were ritually murdered by an agonizing method still utilized today by the Mafia: by tying their necks to their bent legs until they inevitably strangled themselves. The Italian mob calls this torturous execution method “incaprettamento” (literally “ingoatment” because they’re strung up like goats on a spit), but the Neolithic version one-ups even the cruelty of organized crime by burying the victims alive.

A new study of the skeletal remains of two women discovered at the Middle Neolithic (4250-3600 B.C.) site of Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux in southern France has revealed they were ritually murdered by an agonizing method still utilized today by the Mafia: by tying their necks to their bent legs until they inevitably strangled themselves. The Italian mob calls this torturous execution method “incaprettamento” (literally “ingoatment” because they’re strung up like goats on a spit), but the Neolithic version one-ups even the cruelty of organized crime by burying the victims alive.

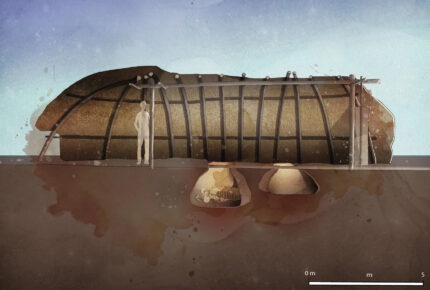

Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux in the central Rhône Valley was a gathering site in the Middle Neolithic, not a residential settlement. Excavations have unearthed numerous silos and pits containing broken grindstones, sacrificed dogs, ceramics and pebble fills. There are also human remains in some of the pits, notably in two pits covered by a wooden structure aligned with the summer and winter solstices.

One of those pits, pit 69, is shaped like a storage silo, but it has no traces of seeds or of having been burned (a sanitizing practice for actual storage silos). It contained the skeletons of three women, one in the center of the pit positioned on her left side with a vase near her head, the other two underneath an overhang. The second was on her back with her legs bent and a heavy piece of grindstone placed on her skull. The third was on her stomach with her neck on the chest of the second woman. Her knees are bent too and she had two pieces of grindstone on her back.

One of those pits, pit 69, is shaped like a storage silo, but it has no traces of seeds or of having been burned (a sanitizing practice for actual storage silos). It contained the skeletons of three women, one in the center of the pit positioned on her left side with a vase near her head, the other two underneath an overhang. The second was on her back with her legs bent and a heavy piece of grindstone placed on her skull. The third was on her stomach with her neck on the chest of the second woman. Her knees are bent too and she had two pieces of grindstone on her back.

Looking into the pit from above at the time of the burial, only the first woman would have been visible. The other two women were obscured by the overhang. They were also crammed into the space, so much so that the grindstone pieces must have been forcefully inserted when the bodies were put in position.

If they were still alive, in conjunction with their positioning beneath the pit’s overhang, then they could no longer move, and breathing became very difficult. Furthermore, since the initial descriptions, numerous forensic studies have been conducted on individuals in similar positions with pressure applied to them, resulting in their deaths. In such a position, death occurs relatively quickly, even if the victims were not drugged or beaten. The prone position induces inadequate ventilation and a decrease in the blood volume pumped by the heart, which can lead to pulseless electrical activity arrest and/or cardiac arrest by asystole. This diagnosis, formerly known as positional asphyxia, could now be better defined as “prone restraint cardiac arrest.” Some individuals are more sensitive than others, but cervical compression is an aggravating factor, as is obstruction of the nose and mouth.

The intriguing position of the lower limbs of woman 3 is also noteworthy. Her legs collapsed to the side as the body decomposed, and from their placement on the corpse, it appears that the knees would have been bent at slightly over 90° with the legs held more or less vertically. Given the woman’s prone position, this suggests a potential case of homicidal ligature strangulation. In this scenario, the woman would have been on her abdomen with a ligature attached to her ankles and neck. The fact that the woman was obstructed by grindstones and the overhang of the storage pit, coupled with the possibility of a tie connecting her ankles to her neck, supports the hypothesis of a deposit while she was still alive. Otherwise, the physical constraints could have been less severe, especially considering that the grindstones were not visible from the outside.

There is evidence of incaprettamento having been used as a method of human sacrifice from other Neolithic sites in Europe. The research team documents the practice in rock art scenes and in burials from 16 graves at 14 archaeological sites stretching from the Czech Republic to Spain and ranging in date from around 5400 B.C. to 3500 B.C.